Prinzessin Aiko wurde heute vom japanischen Kaiser Naruhito mit dem Großkreuz des Ordens der Edlen Krone ausgezeichnet Princess Aiko was awarded today the Grand Cordon of the Order of the Precious Crown by the Japanese Emperor Naruhito

Zur Verleihung des Großkreuzes des Ordens der Edlen Krone gratuliere ich, als Repräsentant des deutschen Volkes in Japan, Ihnen, Prinzessin Aiko 敬宮愛子内親王, sehr herzlich! Für Ihre Verdienste hinsichtlich der Vermittlung der japanischen Kunst im globalen Kontext gebührt Ihnen unser Respekt, und wir freuen uns auf Ihren Besuch in den Museen und Gallerien.

Möge Ihre Arbeit für das japanische Kaiserreich und unser aller Wohl dienlich sein.

Hoch lebe Prinzessin Aiko!

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Orden_der_Edlen_Krone

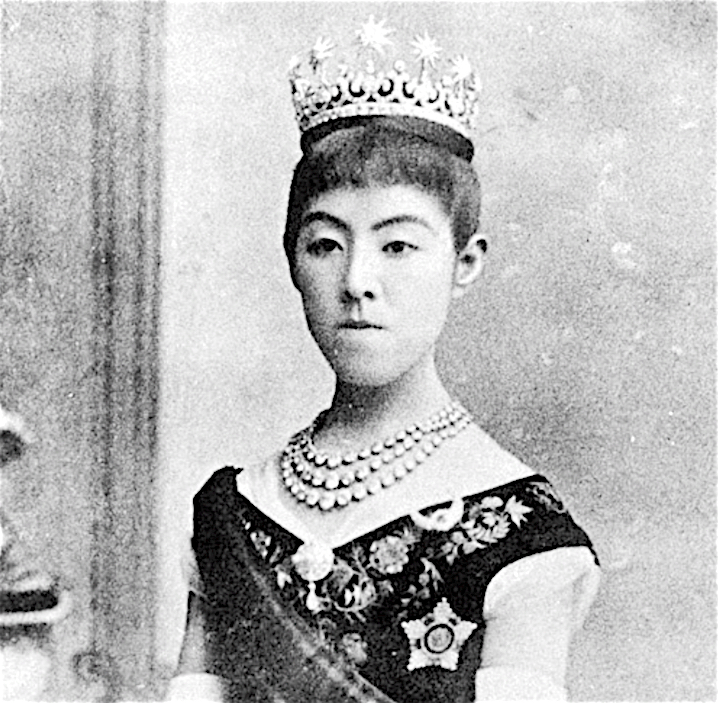

Some information about the tiaras for Japan’s female Imperial Family members:

Japan’s history of tiaras can be traced to the Meiji period (1868-1912). The Meiji-era government aimed to revise a series of unequal treaties exchanged at the end of the Edo period (1603-1867), which led Japan to open its ports and end its national isolation policy, and promoted policies aiming for modernization through Westernization. It was in this context that Japan’s first prime minister, Ito Hirobumi, issued an official notice in 1886 ordering that women of the Imperial Palace wear Western-style clothing.

In January 1887, Empress Dowager Shoken, Emperor Meiji’s wife, wore a German-made court dress, considered the most formal style of ceremonial attire, in New Year ceremonies for the first time.

When Mako Komuro, Crown Prince Akishino (Fumihito)’s elder daughter, came of age in 2011, she wore a tiara by luxury jewelry retailer Wako valued at about 29 million yen (roughly US$255,000). Mako’s younger sister Princess Kako, who turned 20 in 2014, wore a tiara that jewelry maker Mikimoto won the bid to make for around 28 million yen (about US$246,000).

up-date:

Panel submits 2 proposals to stop Japan’s Imperial Family from shrinking

December 22, 2021

A government panel tasked with studying ways to ensure a stable imperial succession submitted Wednesday two proposals to Prime Minister Fumio Kishida that would stop Japan’s royal family from shrinking further, but postponed conclusions regarding specific measures on succession.

The two options — having female members who marry commoners retain their imperial status, and allowing male heirs from former branches to be adopted into the imperial family by revising the 1947 Imperial House Law — seek to address the dwindling number of eligible heirs.

The advisory panel did not touch on whether women or matrilineal imperial members will be eligible to ascend the throne, saying the issue “should be judged in the future,” despite a call by parliament on the government to promptly hold discussions on how to achieve a stable imperial succession in a 2017 nonbinding resolution.

Under the Imperial House Law that limits heirs to a male who has an emperor on his father’s side, there are only three heirs to 61-year-old Emperor Naruhito — his younger brother Crown Prince Fumihito, 56, his nephew Prince Hisahito, 15, and his uncle Prince Hitachi, 86.

According to the report submitted Wednesday, the panel, chaired by former Keio University President Atsushi Seike, concluded that discussions on succession should be pushed back until Prince Hisahito comes of age to marry as engaging in the debate now could “destabilize the throne.”

The report also said that women would not be given a choice about whether to remain in the imperial family after marriage to a commoner, and clarified that descendants of former branches adopted into the imperial family will not have the right to succeed to the throne.

The law currently stipulates that female royals leave the imperial family upon marrying a commoner, but the draft proposal had suggested that women would have the freedom to choose to retain their status.

In the event that the two options fail to secure a sufficient number of eligible heirs, the panel said that making male heirs from former branches imperial family members by law should be considered.

While Kishida has said he will respect the conclusions drawn from the discussions of the panel and submit its report to the Diet, the government still needs to consider whether the proposals may conflict with the Constitution and the will of those involved.

Women born into the imperial family have planned their lives on the basis they will have to give up their royal status should they marry a commoner. It is questionable if they can remain in the imperial family even after marriage without being forced due to a sudden change in the system.

Furthermore, even if women in the imperial family are able to retain their royal status, the government is leaning toward not granting such status to their spouses or children as doing so could pave the way for female monarchs or female-line emperors to which conservative elements have been staunchly opposed.

In such a case, some view it would be impossible to have an imperial family member and those without royal status in one household, as members of the imperial family are bound by different rules and restrictions in such areas as political activity and career choice that do not apply to commoners.

The system also highlights a double standard in which women who wed men in the imperial family will be granted royal status along with their children, but not vice versa.

With regard to allowing male heirs from former branches to be adopted into the imperial family, there are concerns it would violate the Constitution, which prohibits discrimination on the basis of family origin. The Imperial Household Law also prohibits the adoption of children.

The plan hinges on whether any of the eligible descendants actually desire to enter the imperial family, as the Constitution does not allow the government to force adoptions without the consent of involved parties.

The government has yet to confirm the intentions of any of the 11 former branches which share with the imperial family a common ancestor some 600 years ago and had to abandon their status in 1947, two years after the end of World War II.

up-date: 2022/2/22

Mental health issues show women bear brunt of Japan monarchy system

The diagnosis of former princess Mako’s post-traumatic stress disorder prior to her controversial marriage in October has once again highlighted the intense pressure that women in the Japanese imperial family face, with some other members also plagued by mental health issues.

The former princess, 30, who is a niece of Emperor Naruhito, came under massive public scrutiny after it became known that the family of her commoner husband Kei Komuro was involved in a financial dispute.

Her aunt Empress Masako, 58, has long been battling a stress-induced illness related to the pressure she was under to produce a male heir, while former Empress Michiko, 87, the emperor’s mother, became unable to speak for months amid bashing by weekly magazines following her husband’s accession to the throne in 1989.

Both the empress and the former empress were commoners before their marriages to then crown princes.

Under Japan’s 1947 Imperial House Law, women are not eligible to ascend the throne and female members of the imperial family leave the household upon marrying a commoner.

While the former princess and Komuro eventually married on Oct. 26, more than four years after their relationship was made public, traditional ceremonies associated with a royal marriage were not held due to public unease over the money row.

“It is as if there are no human rights (within the imperial family),” said clinical psychologist Sayoko Nobuta.

The Imperial Household Agency revealed prior to the marriage that the former princess had been diagnosed with complex PTSD caused by what she described as psychological abuse the couple and their families received.

Regarding his daughter’s mental health, Crown Prince Fumihito, the emperor’s brother, stressed on the occasion of his 56th birthday in November the need to establish “criteria to refute” erroneous reports.

While the agency has exposed fake news in the past, debunking some reports on its website since 2007, it does not have a clear policy on how to handle such matters.

“Even if (former princess Mako) was told to ignore or not engage with online bashing, one can’t help but notice it in their daily life, and it will chip away at one’s heart before they know it,” said Rika Kayama, a psychiatrist and commentator on social issues.

The former princess’ case is just the latest in a history of mental issues that have befallen women in the imperial family.

In 2004, the agency announced that Empress Masako, then the crown princess, had been diagnosed with adjustment disorder after giving birth in 2001 to Princess Aiko, the only child between her and the emperor. The empress had canceled her official duties the previous year following a bout of shingles.

The empress, a Harvard- and Oxford-educated former diplomat, gave up her career to enter the imperial family in 1993 after accepting a marriage proposal by the then crown prince, having initially declined the offer.

Many speculated that a major cause of her stress was pressure to produce a male heir, as no boys had been born to the imperial family since the birth in 1965 of Crown Prince Fumihito.

The situation abated after Crown Princess Kiko gave birth in 2006 to Prince Hisahito, 15, who is now second in line to the throne.

But unlike former Emperor Akihito and former Empress Michiko, who usually engaged with the public as a couple, the current emperor often performs official duties on his own due to his wife’s condition, although she has been gradually expanding the scope of her activities in recent years.

Still, even the former empress, who became the first commoner to wed an heir to the imperial throne in 1959, was not immune to the pressures of the imperial family.

After the former emperor’s accession to the throne in January 1989, she became the focus of a backlash in weekly magazines triggered by his cultivation of a more approachable image compared to his father Emperor Hirohito, who had taken the throne before World War II when emperors were still regarded as living gods.

On the day of her 59th birthday in October 1993, the former empress collapsed and lost her voice due to psychogenic aphasia.

“The emperor is the symbol of Japan, and the monarchy is a symbol of patriarchy. Therefore, discrimination against women is most pronounced in the imperial family,” Nobuta said, adding that such an environment makes it difficult for bright women to survive.

Nobuta said that former princess Mako, who grew up watching these events and had studied at International Christian University in Tokyo as well as in Britain, must have felt the only way to truly live her life was to leave Japan.

“For former princess Mako, escaping was her main goal, and I think she chose Komuro as the man who could help her achieve this goal,” Nobuta said.

The couple left Japan shortly after registering their marriage to start a new life in New York, where Komuro works as a law clerk at a legal firm.

All eyes are now on Princess Aiko, who turned 20 in December and is now expected to perform official duties as an adult member of the imperial family.

The princess would be entitled to the throne if she were a member of the British or Dutch monarchy, both of which allow the eldest child of the monarch to succeed regardless of gender.

A government panel tasked with studying ways to ensure a stable imperial succession proposed on Dec. 22 allowing female members who marry commoners to retain their imperial status.

But it postponed drawing conclusions regarding whether women or imperial members in the matrilineal line will be eligible to ascend the throne.

In the past, Princess Aiko has sparked concerns and speculation among the public for her prolonged absence from school and a sharp weight loss at one point, but it remains to be seen if the mental health issues that befell the female relatives before her will repeat themselves.

Hajime Sebata, an associate professor of modern Japanese history at Ryukoku University, said that building rapport with citizens through communication, not counterarguments, is key.

“If (the agency) regularly posts (information on royals) on social media and communicates, the public will come to trust the imperial family even if there are criticisms,” he said.

-512x256.jpg)