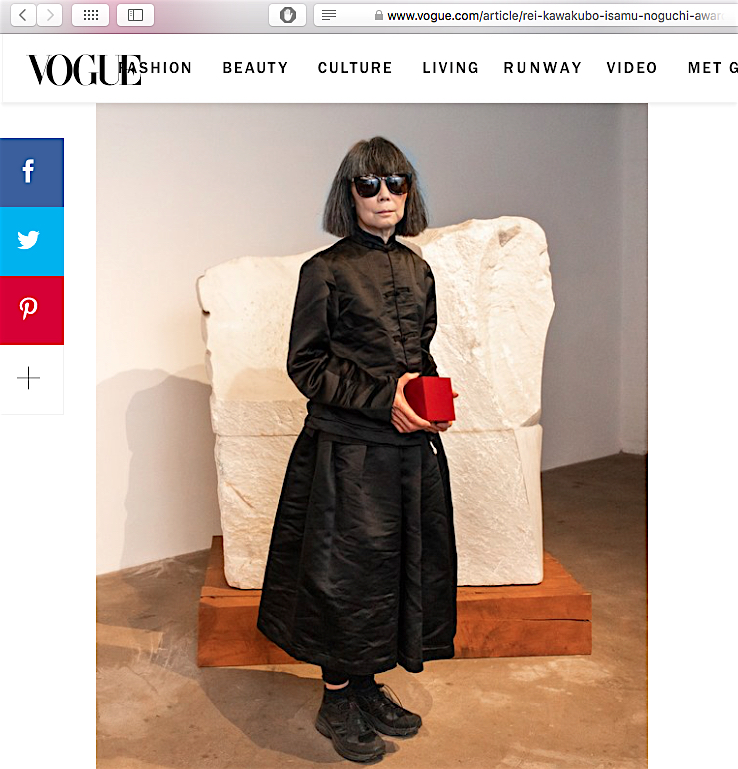

コムデギャルソン ファッションデザイナー 川久保 玲が「イサム・ノグチ賞」を受賞!おめでとうございます! COMME des GARÇONS fashion designer KAWAKUBO Rei wins Isamu Noguchi Award! Congratulations!

米ニューヨークのノグチ美術館(The Noguchi Museum)で5月2日、2019年の「イサム・ノグチ賞」授賞式が行われ、ファッションデザイナー 川久保 玲に賞が贈られる予定です。

同賞は革新性や優れた国際感覚、東西文化交流への貢献など、世界的に活躍した彫刻家イサム・ノグチ(1904~88)の精神に通じる活動を行う建築家と芸術家およびデザイナーに贈られるもので、今年で6回目。日本からはこれまで第1回に杉本博司、第2回に谷口吉生、第3回に安藤忠雄、第4回に千住博、第5回に深沢直人が選ばれている。

The Noguchi Museum has selected renowned fashion designer Rei Kawakubo as recipient of the 2019 Isamu Noguchi Award, given to individuals who share Isamu Noguchi’s spirit of innovation, global consciousness, and commitment to East/West cultural exchange.

Hailed as one of the most brilliant and innovative designers of our time, Rei Kawakubo has consistently disrupted conventional notions not only of beauty, but also of what fashion can be, at once confounding our expectations for clothing and— like Noguchi—challenging the idea that design and art are inherently different endeavors.

Kawakubo, the founder of the avant-garde fashion label COMME des GARÇONS, also co-founded the international retail enterprise Dover Street Market, and her work was the subject of a 2017 exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. She received the Excellence in Design Award from the Harvard University Graduate School of Design in 2000.

In 1993 she was named a Chevalier in the Order of Arts and Letters by the French government. She divides her time between Tokyo and Paris.

This year marks the 50th anniversary of COMME des GARÇONS.

The Award will be presented at the Museum’s annual benefit, on Thursday, May 2, 2019.

The Noguchi Museum

9-01 33rd Road (at Vernon Boulevard) Long Island City, NY

https://www.noguchi.org

Previous recipients of the Isamu Noguchi Award include: 2014—Lord Norman Foster and Hiroshi Sugimoto; 2015—Jasper Morrison and Yoshio Taniguchi; 2016—Tadao Ando and Elyn Zimmerman; 2017—John Pawson and Hiroshi Senju; 2018—Naoto Fukasawa and Edwina von Gal.

Vogue article, up-date 2019/5/7

(Screenshot from the Vogue article)

A Chat With Rei Kawakubo as She Wins the Noguchi Award: “It’s Hard to Find Interesting, New Things”

Vogue, May 4, 2019

quotes:

She began, “I’m not an artist, and because of that I just wanted to say that it’s beyond my honor to receive this award, because I am not an artist. But I try, always, to come up with something new. Things that people have not seen, and I have gone this way for 50 years, and I’m very happy to be recognized for my achievement by receiving this award. Thank you.”

…

Throughout the 154 minutes I spent hawk-eyed on Kawakubo, she remained, as always, respectful and reservedly talkative, speaking through her husband-translator Adrian Joffe. She wore all black, naturally, with her hair perfectly coiffed into a trapezoidal shape. She didn’t really smile or laugh, but paused for jokes just a couple of times with the Consulate General of Japan in New York and Littman. She mostly did not make eye contact, and she definitely didn’t want me to know that in an act of humanness and vanity, right before she took the stage to accept the prize, she mussed her bangs just so.

Eventually I was whisked over to meet Kawakubo and introduced as the reporter with whom she had answered a few email questions earlier in the day. She apologized, through Joffe, that her answers were so short, making the shape of a paragraph with her hand and then shrinking the distance between her forefinger and thumb to just centimeters, the length of a sentence. “It’s okay,” I said. “I expected them to be short.” She issued the tiniest smile, a pleasant nod, and then she turned away to her dinner. I went back to the real world, always a disappointment after you’ve been admitted, even in the most minute way, to the Rei one.

So, here’s what’s up with Rei Kawakubo, in three questions. Don’t be disheartened by her last answer; if her runway collections and the vibrant world she’s created at Dover Street Market are any indication, there are still plenty of secret things that keep her amused.

What parallels do you see between your work and Isamu Noguchi’s?

Maybe it’s the fact that we both, throughout our careers, were always looking for some new image.

What’s the point of fashion today?

I feel, right now, it’s not so interesting. The fashion world is inundated with the same old images everywhere, as this is the prevailing business model. In other words, it’s hard to find interesting, new things.

What excites you?

Recently, nothing.

full text at:

https://www.vogue.com/article/rei-kawakubo-isamu-noguchi-award-interview

COMME des GARÇONS

http://www.comme-des-garcons.com

ノグチ・イサム、ロバート・キャンベル、松下まり子、ヴィルヘルム・フォン・グレーデン& オスカー・ワイルド、アサクサ・キュレーション

NOGUCHI Isamu, Robert Campbell, MATSUSHITA Mariko, Wilhelm van Gloeden & Oscar Wilde, ASAKUSA-Curation

https://art-culture.world/articles/noguchi-isamu-robert-campbell-matsushita-mariko-wilhelm-van-gloeden-oscar-wilde-asakusa-curation/

朝日新聞、2012年1月19日

川久保玲さんロングインタビュー ファッションで前に進む

世の中に漂う閉塞(へいそく)感、そして無力感。ファッション界のフロントランナーとして時代の最先端を鋭敏な感覚で嗅ぎ取り、あるときは時代の風潮にあらがってきた川久保玲。「鉄の女」とも称される彼女は「今」をどうとらえ、どのように前に進もうとしているのか。

■新しさのもつ力 「なんとなく」の風潮に危惧

――出口のない不況が続き、世界中で格差批判も広がっています。高級ブランドを扱う業界には逆風ではないですか。

「どの分野でも、商品の値段や製作費用をいとわず、新しいものを作り出そうとしている人はたくさんいます。そうした姿勢は、どんな状況であっても人が前に進むために必要なものだからです。私にとってはファッションこそが、そうした場なのです」

「一般の人には高くて買えない服でも、新しい動きなり気持ちがみんなに伝わっていくことが大切です。作り手が世界を相手に一生懸命に頑張って発表し、それを誰かが着たり見たりすることで何かを感じて、その輪が広がっていけばいい。新しいというだけでウキウキして、そこから出発できる。ファッションとはそういうものです」

――川久保さんの真骨頂は前衛的なデザインです。でも、世の中の風潮は安定感や着やすさを求める傾向にありますね。

「すぐ着られる簡単な服で満足している人が増えています。他の人と同じ服を着て、そのことに何の疑問も抱かない。服装のことだけではありません。最近の人は強いもの、格好いいもの、新しいものはなくても、今をなんとなく過ごせればいい、と。情熱や興奮、怒り、現状を打ち破ろうという意欲が弱まってきている。そんな風潮に危惧を感じています」

「作り手の側も1番を目指さないとダメ。『2番じゃダメですか』と言い放った政治家がいました。けれども、結果は1番じゃなくても、少なくともその気持ちで臨まなければ。1番を目指すから世界のトップクラスにいることができる。日本は資源がないのだから、先端技術や文化などのソフトパワーで勝負するしかないのです」

――ファッションで個性を表現する必要はない、と考えている人が増えているようです。

「ファッションの分野に限らず本当に個性を表現している人は、人とは違うものを着たり、違うように着こなしたりしているものです。そんな人は、トップモード(流行の最先端)の服でなくても、Tシャツ姿でも『この人は何か持っているな』という雰囲気を醸し出しています。本人の中身が新しければ、着ているものも新しく見える。ファッションとは、それを着ている人の中身も含めたものなのです。最近はグループのタレントが多くなって、みんな同じような服を着て、歌って踊っています。私には不思議です」

――同じといえば、大量生産された安価なファストファッションをどう思いますか。

「いろんなニーズに合った様々なビジネスの形態はあってもいい。強力なクリエーション(創造性)があるものも、即席のファストファッションも、その中間もあるでしょう。でも、ファッションのすべてが民主化される必要はありません」

――「ファッションを民主化する」というのは、ファストファッションの代表格であるH&Mの基本姿勢ですね。

「そういう傾向がどんどん進むと、平等化というか、多様性がなくなり一色になってしまう恐れがある。いいものは人の手や時間、努力が必要なので、どうしても高くなってしまう。効率だけを求めていると、将来的にはいいものが作れなくなってしまいます」

――そのH&Mと数年前にコラボレーションをしました。葛藤はなかったのですか。

「全然なかった。たった2週間のイベントでしたが、私が手がける『コムデギャルソン』の服がマスマーケットにどうアピールできるかに興味があったので」

――かつての流行は世相を切り取るようなものでした。しかし今、ファッションも社会状況も混沌(こんとん)としています。そんな中でのクリエーションとは?

「8年前から、様々なクリエーターたちを集めて自由に表現してもらう『ドーバー・ストリート・マーケット』をロンドンなどに出店しています。価値観や手法が違っていても、集まることで一つのパワーになる。カオス(混沌)の中から相乗効果やアクシデントが起きて、それぞれの作品やブランドも輝きを増しました。同じコンセプトの店を今年3月に東京・銀座にも開店して、6階まで全フロアで展開します」

「世界中のいろんな情報がすぐ手に入る時代ですから、組む相手も探しやすいし、理解もされやすくなっている。それに、ひとひねりした表現の方がファッションとして成り立ちやすく、人の気持ちを浮き立たせます。ファッションはもはや洋服だけを意味しているのではなくて、音楽でも絵でも生活用品でも、新しいことはすべてファッション。インターネットショップにはない刺激が味わえると思います」

■自ら外へ飛び出せ 競争が力を生む

――環境意識が高まり、大量消費への疑問が広がっています。新作を発表し続けるファッション界は、エコと対極では。

「私が新しい服を作るのは、何かを発信し続けることで、地球のどこかで少しでも何かを変えられるきっかけになるのではないか、と考えるからです。環境保護を直接訴えたり、活動に参加したりするやり方もあるでしょうが、私はそういう方法はとりたくない。ちょっと遠回りかもしれませんが、作ったものを通して感覚的に揺さぶる。そのことで問題に気づいてほしいのです」

「物をどんどん作ってちょっと古くなったらもうおしまい、という考え方も持っていません。年2回ずつ新作を出すわけですから、在庫は残ります。売れ残った商品も同じ価格で売り切るように努力しています。東京にリサイクルとデザインを融合した店を出しました。この5年間、在庫を売るためにベルリンなど世界各地に約40店の期間限定ストアも開きました。ビジネスとしてはちょっとつらい面もある。クリエーターというものは真面目にやれば、たいていは貧乏になってしまうものです」

――長引く不況で、消費者やマーケットが保守的になり、業界は挑戦しなくなったと言われます。

「1990年代あたりから、強いもの、新しいものを求めるムードがなくなってきました。それがどんどんひどくなってきて、特にここ5年ほどは業界はすっかり内向きになってしまった。変化を求める気持ちも弱くなった。そんな流れの中で、私は『どこかで見たことがあるようなものはダメ』と自分を懸命に追い込んできました。ところが、それを理解して認めたり、着てみようと思ったりしてくれる人がだんだん減ってきたと肌で感じています」

――川久保さんは31年前、糸がほつれたボロルックでデビューし、世界のファッション界に衝撃を与えました。しかし、いまだに山本耀司さん、三宅一生さんとともに「御三家」と呼ばれ、後に続く世代が出てきません。若い才能を受け入れる土壌が今の業界にはないのでしょうか。

「当時は、作品を発表するたびに強い反応があり、今よりも理解されやすかった。ヨーロッパのファッションはそれほど現代的とはいえなかったので、変化を求める気分があったのでしょう。私も若かったし、反応があったからこそ、さらに強気にチャレンジすることができたのかもしれません。それにパリ・コレでどんなに批判されても、『ああ、そうですか。ではみなさんのお望みのものを作りましょう』とは思いませんでした。『どうしてこれがわからないのか』とさえ感じていました」

――フランスやイタリアは国家をあげてブランドイメージの確立に取り組んでいます。日本でもようやくそうした動きが出てきました。

「それは違うな、と私は思っています。まずは身一つで世界に飛び出して、道ばたでもいいから作品を見せること。世界の人に見てもらうだけでも緊張するし、自分にハッパをかけられる。無駄や失敗があっても、それが次に突き当たった壁を乗り越える力になるのですから」

「社会が豊かになって、そういうガッツがなくなるのは仕方がありません。でも、あえて困難なことに挑戦する強い意志が今こそ必要なのではないでしょうか。『海外』とか『外国』とか、もうそんな時代ではないでしょう。どの国でどういう人たちと仕事をしても土台は違わない。それなのに外に目を向けようとしなくなっている若者が増えています。外へ自力で行って、なるべくたくさんの人と競争しないと、新しい力は生まれません」

「日本国内にだって織りでも、染めや縫製でも素晴らしい職人技術があります。でも効率的な物作りや価格志向が優先される中で、そんな技術や工場がなくなりつつある。彼らと協力するためのデザインやシステムを考えることで世界に発信できる、新しい優れた物作りができるはずです」

■黒から白へ 強さ・希望込めて

――最新コレクションは白一色。驚きました。どんな意味を込めたのですか。

「15分間のショーで表現できることは限られています。今回は、白だけに絞り込むことで、もっと強さを打ち出したいと思ったのです。そこに込めたものは、希望のような気持ちかもしれません。現実は良いことばかりではなく、悪いこともあって、それも人生。そこから解き放たれることがいま大事なのではないか、という問いかけです」

――ウエディングドレスの袖の部分が拘束され、マスクのような帽子があり……。東日本大震災後の日本を表現したという見方もあります。

「それは考え過ぎです。状況が窮屈であれば、自由の意味がわかりますよね。人は自由にならなければ一歩も進めない。それを拘束という形で反対に表現しただけです。新しいことイコール自由、自由イコール前に進むこと。一歩前へ進めば、物事はかなり解決できるものですよ」

――これまでの西洋的な美の基準にあえて異を唱え、新しい美を追求する姿勢から「反骨の母」と呼ばれています。その反骨心はどこからくるのですか。

「世の中の不公平や不条理なことへの憤りでしょうか。本当は私だってそんなに強くはないですよ。ただ、強気のふりも時には必要です。ふりでいいのです。そうしないと前に進めないから。大変だな、どうしよう、としょんぼりしているだけでは何も変わらない。私も毎シーズン、自分の発表した作品が不十分だったのではないかと一度は落ち込んで、それからなんとか立ち直ったつもりになるのです」

――ファッションがあらゆる分野の流行に影響を与えた時代がありました。もはやそんな存在ではないのでは。

「それは時代の変化で、そういうものかもしれない、もう負けかな、と思うこともあります。状況を変えられていないのは事実ですから。けれども、ファッションにはなお、人を前向きにさせて、何か新しいことに挑戦させるきっかけになる力があると信じています」

「ファッションは非常に感覚的なものなので軽く見られがちですが、実は人間に必要な力を持っています。理屈やデータではなくて、何か大事なことを伝えて感じてもらう。アートとも違って、人が身につけることで深い理解が生まれます。軽薄とみられがちな部分も含めて私はファッションが好きです。ファッションはたった今、この瞬間だけのもので、それを今着たいと思うから、ファッションなのです。はかないもの、泡のようなもの。そんな刹那(せつな)的なものだからこそ、今とても大切なことを伝えることができるのです」

■取材を終えて

ファッション界では珍しく、写真の被写体になることを強く嫌い、また寡黙なデザイナーとして知られる。今回も作品と震災の関係については、言葉少なかった。その代わり、発表する作品はいつも全く違ったテーマや新しい手法で、世の中に強く訴えかける。見るものを戸惑わせ、深く考えさせ、心を揺さぶる。

ぼろぼろにほつれた服を引っさげて、パリモードの伝統に風穴を開けたパリ・コレデビューから31年。その間ずっと反骨の精神を貫いてきた。サングラスを好み、近寄りがたい雰囲気を漂わせる。だがインタビューではサングラスを外し、「時には強気のふりをしているだけ」とは意外だった。

大量消費社会が行き詰まりをみせ、既存の価値観が壊れる中、「ふり」をしながらでも自らを鼓舞して前に進むこと、それが新しい流れを生み出すためにきっと必要なのだろう。(編集委員・高橋牧子)

川久保玲(かわくぼ・れい)さん

1942年、東京生まれ。慶応義塾大学文学部卒業後、大手繊維メーカー宣伝部に入社。69年、「少年のように」を意味する仏語「コムデギャルソン」の名称で婦人服の製造・販売を始め、73年に会社を設立。75年、東京で初のショーを開き、81年からパリ・コレクションに参加。同時にデビューした山本耀司さんと共に、オートクチュールを頂点とする西欧モードを揺るがす「黒の衝撃」と騒がれた。その穴のあいた黒い服は日本でも「カラス族」「ボロルック」として流行。その後もパッドを体につけた「こぶドレス」(96年)、縫製の代わりに粘着テープで接着したジャケット(00年)など次々と話題作を発表し、前衛派の旗手として不動の座を保つ。朝日賞、毎日ファッション大賞、英国王立芸術大学名誉博士号、仏国家功労章などを受けた。

http://www.asahi.com/fashion/beauty/TKY201201180360.html

A rare interview for vogue in 2017:

On the Eve of the Comme des Garçons Retrospective, the Notoriously Reclusive Rei Kawakubo Speaks Out

VOGUE, April 14, 2017 by Lynn Yaeger

On a rain-soaked March afternoon in Paris, in a former nineteenth-century ballroom in the Eighteenth Arrondissement, Rei Kawakubo, the founder of Comme des Garçons, is staging her fall 2017 show. A slow procession of young women, their arms often bound to their bodies, giving them the look of dressmaker dummies, are swaddled in bulbous, undulating layers, rendered in what could be insulation material or tinfoil or a substance reminiscent of a brown paper bag. On their heads are wigs of coiled silver curls that were inspired, the master hairstylist Julien d’Ys says, by a sponge he found at the supermarket. On their feet is the one concession to practicality—the trainers that Comme has designed for Nike.

At the end of the show Anna Cleveland emerges, dressed in a black-and-white confection that recalls a giant melting wedding cake, and does a little twirly dance, like a broken music-box doll. Since 2013, Kawakubo has ditched the conventional catwalk in favor of this kind of avant-garde parade. Closer perhaps to performance art than fashion show, these living sculptures elicit a wide range of emotions—from wild applause, even tears, to bewilderment bordering on annoyance.

Eight weeks after this show, Comme des Garçons will be the subject of “Rei Kawakubo/Comme des Garçons: Art of the In-Between,” the Metropolitan Museum of Art Costume Institute’s spring 2017 exhibition—only the second such show to honor a living designer, the other recipient being Yves Saint Laurent in 1983.

Kawakubo is undeniably influential, a cult figure in the industry, but her designs are far from Saint Laurent’s easy trenches and sexy smokings. When she burst on the scene—her first Paris show was in 1981—she shocked the fashion world with her droopy, dark silhouettes, her reliance on plebeian fabrics like black polyester, her radical abandonment of the conventional notions of attractiveness. Unglamorous her garments may have been, but they immediately caught the eye of artists and outliers at odds with the big shoulders and disco dramatics that ruled runways in the eighties. In the decades that followed, Kawakubo expanded her repertoire, exploring the relationship of the body to clothing in ways both raw and uncompromising. From the beginning of her career, she has been stunningly audacious. If we now accept unfinished hems, asymmetry, a palette of unrelenting black, and overblown and deconstructed silhouettes as just another part of fashion’s lexicon, we can thank Kawakubo for pursuing this innovation with ferocious conviction.

“I really think her influence is so huge, but sometimes it’s subtle. It’s not about copying her; it’s the purity of her vision,” Andrew Bolton, the curator in charge of the Costume Institute, tells me over tea in the Salon Proust at the Ritz. The exquisite room, with its book-lined walls and cozy elegance, is a profoundly different setting than the upcoming exhibition—which Bolton says will be an austere, all-white maze hosting approximately 150 Comme ensembles. “Rei was really involved in the design of the exhibit,” he says.

As visitors travel through this labyrinth, they will encounter examples from collections including the house’s renowned spring 2005 Ballerina Motorbike show, which combined tutus and leather jackets (and which Kawakubo described as “Harley-Davidson loves Margot Fonteyn”). If the Ballerina Biker has a butch prettiness, other designs are far more challenging: 1997’s reviled Body Meets Dress—Dress Meets Body, colloquially known as the “lumps and bumps” collection, featured stretch nylon clothing distorted with asymmetrical padding, resulting in a swelling effect that many fashion critics compared to tumors.

I do not own a lumpy-bumpy dress, but I do possess a great many examples of Kawakubo’s work. I have been enamored of Comme des Garçons from the first time I saw it, at the original Barneys on Seventeenth Street, more than 30 years ago. It was a navy wool schoolgirl smock that stole my heart, and it cost $260—at a time when I was earning $135 a week. I told a credit union that my refrigerator broke, got the money, and bought the dress. I thought it would change my life, and it did. Over the years, so many other Comme garments and shows have spoken to me—the 2006 masculine/feminine Persona collection, the 2012 2-D Paper Doll coats. These clothes, by uprooting conventional notions of fashion, of beauty, helped me find my own way to shine.

At 7:45 a.m. the day after the show, I arrive at the Comme headquarters on the Place Vendôme. I have an interview scheduled with Kawakubo later in the morning, but I am allowed to sit in on an early session during which the notoriously taciturn designer will be taking an audience of employees through last night’s collection. After a screening of a video of the show, watched in reverent silence, Kawakubo takes the stage. With her husband, Adrian Joffe—also the president of CDG and Dover Street Market—serving as translator, she tells the audience the collection is about “the future of the silhouettes,” “a way of expressing the notion of un-fabric,” and also that “the commercial collection is mostly using un-fabric.” Those three thoughts constitute the entire presentation.

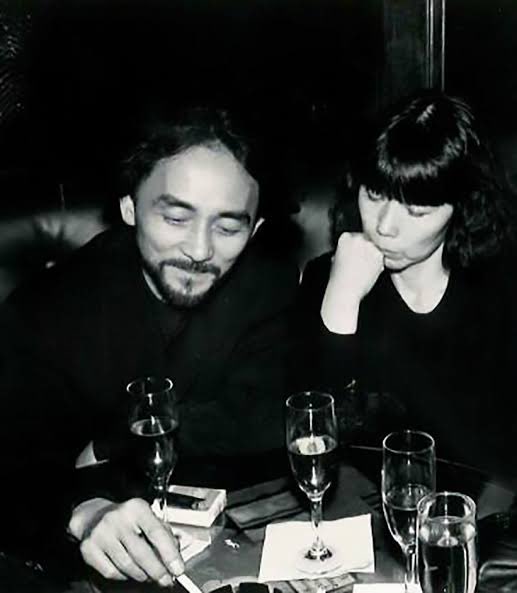

Joffe, South African by birth and ten years Kawakubo’s junior, joined the company in 1987. He and Kawakubo married in 1992, at the Paris City Hall. It is a partnership with its own rhythms—while Joffe is based in Paris, his wife lives in Tokyo, in the upscale Aoyama neighborhood, walking distance to CDG’s flagship. (Kawakubo is reportedly the first one in the office in the morning and the last to leave at night.) When you see them together, he seems to serve as her protector—not just translating for her, but also shielding her from inquiries deemed too prying.

Only at Comme could the un-fabric clothes that hang in the showroom be considered a “commercial collection”—skirts sport stiff tubular growths; jackets are faced with a shiny silver substance that looks like Mylar and turns out to be vaporized aluminum and polyester film. Still, though these pieces may be highly eccentric, they are not upholstery cocoons—they can leave the catwalk and take to the streets. “Collection is Rei’s ‘creation,’ and the commercial collection is her ‘style,’ ” an employee tells me, and I am reminded of the political adage that one campaigns in poetry and governs in prose. Thierry Dreyfus, who is responsible for the lighting for Kawakubo’s shows, tells me something oddly similar: “I think Rei’s work is poetry,” he says. “It is like when you read Whitman—you participate, and then you share something; but nothing is said, nothing that can be explained.”

Poetry it may be, but one should not underestimate the prose component—in the decades since the label was founded in 1969 (early designs bear a striking resemblance to Sonia Rykiel), CDG has expanded to include 130 or so stores all over the world selling not just the main label but subsidiary lower-priced lines, including the Play merchandise, with its heart-face trademark, and limited-edition collaborations with companies from Hermès to Speedo.

Kawakubo never went to fashion school—she says she got a job at a big fiber company, purely by chance, and the whole thing happened by accident. And while that may be true, it also serves as another example of the mists that envelop this brand. In addition to her own work, Kawakubo’s atelier has developed and promoted a roster of designers that include Junya Watanabe, Kei Ninomiya, and Chitose Abe, who worked at CDG before starting Sacai. In 2004, Kawakubo and Joffe opened the first Dover Street Market in London, and there are now five branches. DSM could be described as a sort of hipster department store featuring a mix of world-class brands—Alaïa! Balenciaga! Gucci!—and an assortment of tiny labels Kawakubo and her team have discovered. (She is always on the prowl—last spring, she was spotted at nightlife impresario Ladyfag’s Pop Souk in the East Village, a showcase for the kinds of fashion kids who whip up their samples in Bed-Stuy bedsits.)

At exactly 10:30 a.m., I am sitting across from Kawakubo to discuss poetry, prose, and her upcoming exhibition. Half hidden behind a Mac laptop, she is disarmingly tiny, wrenlike, clad in a miniature leather biker jacket and a long plaid skirt—her uniform. If I am nervous, she is even more skittish. (This shared shyness is nothing new: Many years ago, when Comme launched its first perfume, there was a party for her at Barneys. Everyone was having fun, except for two people standing timidly in opposite corners, looking down at the floor—Kawakubo and me.)

I arrive with the knowledge that many have faltered on the shoals of the Comme interview—and that talk of the intersection of art and fashion leads to one-word answers—so I decide to try a different tack. “What makes you laugh?” I ask. The reply: Nothing. When I ask her if the success of the brand and her legendary status has surprised her, she replies that she is not doing anything special: “I am just working day-to-day with what I believe . . . just dealing with my work—just like everybody else.” (Joffe is translating her remarks for me, though Kawakubo seems to understand English and listens intently when I speak to her, nodding and sometimes even offering a semblance of a smile.)

Well, OK, I say, but surely ordinary people aren’t having Met exhibitions? “It’s a halfway thing. It’s like something on the road to something—it’s not a final thing. There’s no guarantee. . . . Maybe after the Met I won’t be able to make anything? Maybe the company will go down; I’m not sure.”

She asks if I understand what she is driving at, and I decide to tell a story about how Jane Fonda once asked her dad, Henry, why he took every dumb role that came his way even after he was a Hollywood legend, and how Henry replied that maybe he would never get another chance to act. Kawakubo loves this.

She warms up a bit, sharing that she enjoys the films of Steve McQueen (the director, not the late actor and race-car enthusiast.) She likes London because there are lots of trees. She doesn’t particularly care for Paris, but she felt that it was the international center for fashion and wanted to be there when she stopped showing in Japan. She thinks New York is all about work.

To lighten the mood further, I ask her what she is going to wear to the Met, and she shakes her head and says she’s not going. “Yes, you are going!” Joffe tells her. “You don’t have to stand on the red carpet, but you have to go to the dinner!” In that case, she says, she will wear what she is wearing now—what she wears every day.

I gingerly approach the subject of the exhibition itself, and she declares that while she never wanted to do a retrospective, she has made some compromises. “It’s a Met show for Comme des Garçons, not a Comme des Garçons show at the Met,” she says. Like many artists, she is deeply uncomfortable with the thought of another pair of hands, another set of eyes arranging and interpreting her work, even if those hands and eyes belong to Bolton, who has an intense appreciation and respect for her creations.

Speaking with her, you cannot help but get a sense of her intensity, her solitude—and, in truth, a profound sadness. Since she is loath to acknowledge her success, I ask her what she considers her biggest failure. “Maybe the fact that it’s such hard work to do what I do and so much torture and living in hell and getting so tired working dawn to midnight every day for the last 40 years—maybe that would be called a failure in some sense,” she replies. When people insist they are blown away by something she has done, she doesn’t believe them. After all, she says, no one has ever come backstage after a show and said, “This is not as good as last time.”

But sometimes people truly are blown away by outsize imagination, sheer nerve, an artist’s crazy vision! Kawakubo may eschew this whole notion of art-as-fashion, but Bolton is sure that her originality, her stunning creativity, will enrapture visitors. “I know we will get people who will laugh at it and not see the intention—the ones who reduce fashion to wearability,” he says. “But I hope most people will be inspired by it.”

And Bolton has his own version of my refrigerator story, though his involves not a schoolgirl smock but a sweater from the fall 1982 collection, a pullover full of holes. He was obsessed with finding this rare item for the exhibition, and finally, at the last second, one turned up. Known as “the Lace Sweater,” it will be proudly on display somewhere in the maze, and you will also be able to buy a version in the exhibition store—a perfect blending of art and commerce, a salute, in all its bohemian grandeur, to a brand and a woman whose ornery, uncompromising creations have transcended the mere categories of fashion and art.

http://www.vogue.com/article/rei-kawakubo-interview-comme-des-garcons-2017-met-museum-costume-exhibit

Behind Comme des Garcons Stands Zen-Loving Contrarian CEO

by Joel Weber, October 8, 2014

Oct. 8 (Bloomberg) — On a gray spring morning in Paris, behind the facade of an 18th century building on the Place Vendome, a flying insect has somehow made its way through an arched doorway, past a limestone courtyard and into the headquarters of Comme des Garcons International, where it is now buzzing around the head of Chief Executive Officer Adrian Joffe.

Not for long.

As Joffe sits at a glass table in his office, calmly discussing the relationship between artistic integrity and profit, he suddenly raises his right arm and executes a rapid swatting motion reminiscent of an Andy Roddick first serve. In a split second, the fly is gone and Joffe continues speaking, making no acknowledgment of the interruption aside from a barely perceptible grin.

To those who aren’t familiar with Joffe — a seemingly mild-mannered executive with a background in Zen Buddhism and linguistics — this matter-of-fact extermination of another living being might seem surprising. But as Bloomberg Pursuits magazine reports in its Autumn 2014 issue, those who know him well would recognize one of his most-marked qualities: not a killer instinct exactly but, rather, a clean efficiency, a knack for swiftly removing distractions so as to focus on what’s important.

Innovative Brand

Comme des Garcons, founded in Tokyo 45 years ago by the reclusive designer Rei Kawakubo — Joffe’s wife since 1992 — is perhaps the most enduringly innovative fashion brand of modern times. From the start, Kawakubo’s goal has been to rise above market forces to freely create new things, be they jackets with three sleeves or androgynous, abstract garments that upend standard notions of clothing, gender and beauty.

Despite its renegade bona fides, Comme, as its devotees call it, is also a business, and it’s up to Joffe to help keep it profitable. At a time when the art-commerce balancing act is a daunting challenge for many creative companies, Joffe, who has no formal training in either art or commerce, has become an unlikely master of juggling both. His ideas often seem uncopyable — until they’re widely copied. Such was the case with Comme’s guerrilla stores, one-off, limited-run boutiques that served as the prototypes for today’s ubiquitous pop-up shops.

Creativity

Pharrell Williams — whose new unisex scent with Comme puts him in an esteemed club of fragrance collaborators that includes the design firm Artek and London’s Serpentine Gallery — says that creativity remains Joffe’s top priority, with commerce running a very close second.

“Money doesn’t make ideas; ideas make money,” Williams observes. He describes Comme des Garcons as a kind of brilliant biosphere, with Joffe as the curator who gives Kawakubo’s creations their essential context. “If Comme is like a snow globe, Adrian is the water,” Williams says.

Joffe certainly doesn’t fit the standard profile of a 61-year-old CEO — and not just because he dresses in head-to-toe black, often with a pair of graffitied Doc Martens on his feet. The shoes are a limited-edition Comme collaboration adorned with slogans by his wife, including, significantly, “My energy comes from my freedom.”

One of Joffe’s many tasks at the company is to act as interpreter and gatekeeper for the resolutely private Kawakubo, who speaks little English and shows no interest in making herself understood to the outside world.

“That’s the worst part of my job,” Joffe says. “It’s hard to explain her, and I don’t really want to. But I am somewhat of a realist, and for business, you have to try.”

Perpetual Innovation

Given its commitment to perpetual innovation, Comme des Garcons (“Like Boys” in French) is seen as a concept as much as a clothing label, but its essence is “almost impossible to put into words,” says Ronnie Cooke Newhouse, a London-based creative director who has collaborated with Joffe and Kawakubo since the 1990s. “It’s like an unspoken language. You never learn the language; you just know it.”

Joffe’s role at the $230 million company is equally hard to define, since Kawakubo remains the brand’s designer and guru-in-chief. (She still helms the Japanese part of the business from its headquarters in Tokyo, where she lives.) However, in addition to overseeing worldwide retail operations, Joffe is in charge of Comme’s acclaimed Dover Street Market, a deconstructed department store with branches in London, New York and Tokyo, as well as the company’s pioneering fragrance arm, which has launched 77 scents to date.

Everything Zen

Joffe got into the business by accident. Born in South Africa and raised in the U.K., he studied Japanese and Tibetan culture at the University of London before moving to Japan without a job in 1977. In Osaka, he perfected his Japanese, deepened his Zen meditation practice and gave serious consideration to a career as a monk while washing dishes at a bar called the Pasadena Inn.

After returning to London to start his Ph.D. on Tibetan and Zen Buddhism, Joffe began helping his sister, Rose (later the co-founder of Paris’s celebrated Rose Bakery), with a fledgling fashion business until Comme des Garcons hired him in 1987 as a commercial director based in Paris.

It was around then that Joffe first met Kawakubo, who, as usual, didn’t say much but didn’t need to; Joffe remembers being instantly struck by the “very intense aura” others had told him about.

“She walks into a room, and the air seems to change,” he says. “There’s no one I know like that.”

Marriage

The two became personally involved in 1991 and within a year got married at Paris’s Hotel de Ville. (Kawakubo doesn’t discuss Joffe or her private life in the press and wouldn’t be interviewed for this or any article about her husband. “No way,” Joffe says.)

By 1993, Joffe was president of the company and looking for new ways to apply Comme’s rule-breaking philosophy to the business side. Kawakubo, who Joffe says has an acute business mind herself, had never been interested in fragrance, but at Joffe’s urging, they began to explore the possibility, while of course ignoring the established rules of the beauty industry.

“In Japan, there’s no culture of perfume,” Joffe says. “Rei didn’t like the idea of putting on a perfume to seduce somebody. So our thinking was, What’s a fragrance for?”

One answer came with the launch in 1998 of Odeur 53, an “anti-perfume” whose notes included “flaming rock,” “flash of metal” and “wash drying in the wind.”

There were themed series of fragrances under rubrics like Synthetic, which evoked the smells of the city with scents such as Dry Clean and Tar. (“That was a weird one,” Joffe acknowledges with a grin.) A 2007 collaboration with couture milliner Stephen Jones produced a spicy-floral eau de toilette that, according to its creator, evoked hats.

New Scent

Williams, who counts himself among Comme’s die-hard fans, began discussing a possible collaboration with Joffe and Kawakubo in 2012. Although his new, woodsy scent — called Girl, just like his latest record, but also targeted toward boys — will clearly benefit from the singer’s current megastardom, it’s nothing like the mass-produced, profit-driven celebrity fragrances that now litter the market. Concocted in Paris with perfume master Christian Astuguevieille, Girl will be sold in Comme des Garcons stores and at Sephora, with no advertising.

When asked why he went with the niche Comme at a time when he could have released a blockbuster fragrance with any major company of his choosing, Williams says, “I wanted to be with the best.” He adds, “Rei and Adrian make no concessions to the way things are done by everybody else.”

Comme’s next fragrance, due in 2015, is a collaboration with Grace Coddington, the flame-haired, 73-year-old creative director of American Vogue.

Guerrilla Stores

One of Joffe’s most game-changing inventions dates to 2004, when he began opening Comme des Garcons’ first guerrilla stores — raw retail spaces in outlying areas of Berlin and other cities that closed by design after a year. He has also worked with Kawakubo to strategize on the label’s many offshoot lines such as Black and Play, the somewhat more wearable (and affordable) alternatives to the main collections shown on Paris runways.

However, the duo’s retail vision reaches its fullest and most delirious expression at Dover Street Market, their multibrand mecca that’s part fashion emporium, part group art installation and part Pee-wee’s Playhouse.

‘Formulaic’ Stores

Traditional department stores, Joffe says, “are just so formulaic, aren’t they? You walk in and it’s, like, random scarves and furniture and horrible jewelry. There’s the men’s floor, and there’s the ladies floor.”

At Dover Street’s New York outpost, opened in December, what you’ll find instead is a Biotopological Scale-Juggling Escalator — an enclosed stairway that purports to reverse the aging process, according to its creator, Madeline Gins — and soundscapes by artist Calx Vive. The clothes are a mix of hard-to-find international labels, cutting-edge street wear, Comme’s own lines and samplings of top luxury brands such as Prada and Louis Vuitton.

Indeed, both Miuccia Prada and Vuitton creative director Nicolas Ghesquiere personally created their own dramatic spaces for the store, and Prada even designed an exclusive mini-collection for it. Joffe says these megabrands are surprisingly willing to adapt to the quirks of the Comme world.

‘Real Dialogue’

“Elsewhere, they’re used to getting exactly what they want — the biggest, the highest, the widest,” he says. “But they know we’re as strong as they are, so they get the rare chance to engage in a real dialogue and be more free in their corporate structure.”

Coddington adds that Joffe has little use for middlemen — including lawyers — who often complicate dealings in the fashion world.

“When we met about the perfume contract, Adrian said, ‘My lawyer is me,’ which I love,” Coddington recalls. “Of course, I think that means he’s very careful about whom he connects with.”

At all three branches of Dover Street, Kawakubo designs the overarching interiors and Joffe chooses the retail mix. James Gilchrist, the New York store’s general manager, says that when he was hiring the sales staff, his main directive from Joffe was “the more eccentric, the better.” Gilchrist remembers walking down a sidewalk in SoHo with Joffe and seeing a “really amazing guy with a big beard and weird mustache and piercings and a fake cat on his shoulder. And Adrian was like, ‘We need him.’”

‘Wake-Up Call’

On opening day last year, 3,000 fashion-obsessed fans showed up at the New York store. A review on Style.com called the place a “wake-up call for the retail industry,” citing the store’s ability to provoke surprise and delight, rare qualities in a shopping era dominated by Amazon Prime.

With so many big talents — and their attendant egos — sharing one space, it’s no surprise that Joffe had a few major dramas to referee. James Jebbia, the founder of cult skate-wear label Supreme, became angry when he learned that the minimalist, white-walled space he created for the seventh floor would be juxtaposed with Prada’s dazzling installation, a kind of urban spaceship featuring huge murals and mannequins painted by Brooklyn street artist Gabriel Specter. Joffe blames himself for the clash.

“We like people to work in isolation,” he says, “so we didn’t tell Prada how the Supreme space was going to be, and we didn’t tell Supreme how the Prada space was going to be.”

Jebbia now has good reason to be happy with the arrangement, since a line of Supreme fanatics forms in front of Dover Street every Thursday, when the company’s new stock hits the racks.

Buddhist Training

In these matters and others, Joffe’s Buddhist training comes in handy. Although he dropped his daily meditation practice shortly after leaving Japan (“It just happened — living in the West, you know”), the philosophy, with its emphasis on impermanence and lack of attachment, still guides him.

“It’s a way of understanding the world — the big world and your little world,” he says. “It has kept me sane, I think. Otherwise, I just don’t know whether I could have survived in this business.”

The Zen approach extends to Joffe’s minimalist home in Paris’s Marais district, which Kawakubo designed. Cheerfully deflecting my attempt to see where he lives (“Not going to happen!” he says), Joffe describes it with one word: empty. The walls are mostly bare, and there are only a handful of pieces of furniture, including a Le Corbusier chair and a Poul Kjaerholm table. Joffe also has a small apartment in Marseille that’s “even more empty,” containing little besides an Ikea futon.

Busy Biosphere

Evidently, life inside the busy Comme des Garcons biosphere doesn’t leave a lot of time for hedonistic pleasures. Joffe sees Kawakubo about once a month, during her trips to Paris and his to Tokyo, but otherwise lives by himself. While off duty, he does a lot of walking and a little boxing, attempting to stave off what he calls “the horror of getting fat and old at the same time.”

Unlike other prominent fashion couples — say, Miuccia Prada and Patrizio Bertelli or Valentino Garavani and Giancarlo Giammetti — Joffe and Kawakubo have no interest in stockpiling contemporary art or sailing the Mediterranean with Naomi Campbell.

“They are not into yachts,” Gilchrist observes dryly.

Newhouse adds: “It’s clear that if they wanted to be materialistic, they could be. But I think they live exactly the way they choose to live.”

A pressing question in the fashion world is how long their unique way of living and working can go on. Kawakubo turns 72 in October, and her self-imposed ban on copying anyone — including herself — is getting more constricting every season.

‘Weight of Experience’

“It’s really torture for her now,” Joffe says. “Not because of her age, but because she’s done so many new things every six months for 45 years. You can imagine the weight of experience.”

Will there be a Comme des Garcons after Kawakubo?

“It’s a very difficult question,” Joffe says. “It’s inconceivable that anyone else could design Comme des Garcons, the line.” But he says he can imagine partnering with “someone else with a vision,” who could retain the spirit of the brand in some other way. “No decisions have been made,” he says. “I think we’ve got five years. There’s no hurry, but I’m kind of pushing to sort it out and create a strategy.”

Girl Packaging

In the meantime, Joffe will continue doing his best to brook no compromise — unless it’s of his own making. When executives at Sephora reviewed the packaging for Girl — a bottle designed by the artist KAWS inside a box made of transparent plastic — they pushed Joffe to change the box.

“They thought the plastic looked cheap, even though it was more expensive,” Joffe says. He agreed to try a heavy cardboard, and “in the end, they were right,” he says.

However, Sephora also wanted to change the dimensions of the box to make it more suitable for display. Joffe held firm. “They said, ‘Can you just make it 5 millimeters smaller?’ And we said, ‘No. It has to be that size, because that’s the size we want.’”

Joffe now admits the box may indeed be too big to fit properly on store shelves, but his knowing smile indicates it’s not an insurmountable problem.

“We just might have to redo all the shelves,” he says.

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2014-10-07/behind-comme-des-garcons-stands-zen-loving-contrarian-ceo

川久保玲と山本耀司の関係性って不思議だ。

かつては恋人であり、ライバルであり同士でもあったけれど、耀司さんは川久保さんについて話すことが多いことに対して、川久保さんはブランドとしてのヨウジや山本耀司について語ることはほぼ皆無。

男と女の違いと云えばそれまでだけど、川久保さんは必要最低限の言葉しか公にはしない。

ご自身の言葉を借りれば「作品が私の全て」これに尽きるだろう。

Link_https://twitter.com/tokyofashionlab/status/1656941630908399616

ここに載せた文章は、すべて「好意によりクリエーティブ・コモン・センス」の文脈で、日本美術史の記録の為に発表致します。

Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial-NoDerivative Works

photos and texts: cccs courtesy creative common sense