アマンダ・ゴーマンの「私たちがのぼる丘」 Amanda Gorman's 'The Hill We Climb'

第46代アメリカ大統領ジョー・バイデン氏の就任式が1月20日にワシントンで行われました。その時、詩の朗読という伝統があり、世界に感動を与えた22歳の詩人アマンダ・ゴーマンさんが作詩した「The Hill We Climb(私たちがのぼる丘)」を以下に紹介させていただきます。

(あえて日本語とドイツ語の翻訳、4バージョン、付き)

SLAM Poetryやラップのリズムの特徴も含まれているので、残念ながら、非常に翻訳し難い状態です。文化の橋渡しという役割でありながら、今回の場合もそのまま、「Lost in Translation」に終わってしまう。通訳者/翻訳者の仕事がいかに難しいかが、この4バージョンを比べるとお分かりになるでしょう。もっとこの世界で働く方々を尊重しなければなりません。

また、ほとんどの日本人アーティストは英語が苦手です。日本の美術界の予算が少なすぎることは今なお問題ですが、給料が低い面で同じく、日本純文学翻訳者も少ないのが現実です。

(一生懸命勉強しても、僕の日本語の語彙、能力の限界を感じてしまいます。)

では、ゴーマンのインスタグラムのアカウントを是非チェック。

Link_to_https://www.instagram.com/amandascgorman/

日本語のテロップはこちらです:

https://news.tbs.co.jp/newseye/tbs_newseye4181148.html

The Hill We Climb

A 私たちがのぼる丘

B 私たちがのぼる丘

C Der Berg, auf den wir steigen

D Der Hügel, den wir erklimmen

When day comes, we ask ourselves,

A 一日が始まると、自分に問いかける

B 夜が明ける時、私たちは自分に問いかける。決して終わらないように見える陰の中、一体どこに光があるのかと。

C Wenn der Tag kommt, fragen wir uns,

D Der Morgen graut, und wir fragen uns,

where can we find light in this never-ending shade?

A この終わりのない暗がりのどこに光は差しているのかと

C wo finden wir Licht in diesem endlosen Schatten?

D wo nur, in diesen endlosen Schatten, finden wir Licht?

The loss we carry,

A 私たちは喪失感を抱えながら

B 私たちは、失なったものを背負い、海を渡らねばならない。

C Der Verlust, den wir tragen,

D Da sind Verluste, die wir mitschleppen,

a sea we must wade.

A 海原を進まねばならない

C ein Meer zu durchwaten.

D die See, die wir durchwaten müssen.

We’ve braved the belly of the beast.

A 私たちは窮地にも勇敢に立ち向った

B 私たちは、窮地に立ち向かい、学んできた。静けさが平和だとは限らないことを。そして「正義」を定義する規範や概念が、必ずしも常に正しいとは限らないことを。

C Wir waren im Bauch des Ungeheuers.

D Die gierige Bestie, ihr haben wir getrotzt,

We’ve learned that quiet isn’t always peace.

A 静寂は必ずしも平和ではなく

C Wir haben erfahren, dass Stille nicht unbedingt Friede ist.

D gelernt, dass Ruhe nicht wirklich Frieden heißt,

And the norms and notions

A 正しいとされる常識や概念が

C Und die Regeln und Wahrnehmungen

D dass die Normen, die Vorstellungen,

of what just is, isn’t always just-ice.

A いつも“正義”とは限らない

C von dem was da ist, das muss nicht Gerechtigkeit sein.

D das was just ist, nicht immer auch recht ist.

And yet the dawn is ours

A それでも知らぬ間に夜は明ける

B それでも、私たちが気づく前に、夜明けはやってくる。

C Und doch ist der Morgen unser

D Der Morgen aber gehört uns

before we knew it.

A どうにかそれをやり、どうにかやりすごし

C bevor wir’s bemerken.

D und das, noch bevor wir’s wussten.

Somehow we do it.

B なんとかして、私たちはやり遂げるのだ。

C Irgendwie schaffen wir’s.

D Wir schaffen das, irgendwie.

Somehow we’ve weathered and witnessed

A そして目の当たりにした

B なんとかして、私たちは乗り越え、そして目にした。この国は崩壊したわけではなく、ただ未完成だったのだと。

C Irgendwie haben wir sie gesehen und überstanden,

D Wir haben’s überstanden, irgendwie;

a nation that isn’t broken,

A 壊れていないけれど、ただ未完成の国を

C eine Nation, die nicht zerstört ist,

D haben eine Nation erlebt, die nicht kaputt ist,

but simply unfinished.

C sondern noch nicht fertig.

D unfertig nur.

We, the successors of a country and a time

A 私たちはこの国と時代の継承者だ

B 奴隷の子孫で、シングルマザーに育てられた痩せっぽちの黒人の女の子が、大統領になるのを夢見ることができる。その子が、ひとりのために詩を朗読する。私たちは、そんな国と時代の継承者なのだ。

C Wir, die ein Land erben und eine Zeit,

D Wir, Nachfahren eines Landes und einer Zeit,

where a skinny Black girl

A ここでは奴隷の子孫で母子家庭で育ったやせた黒人少女も

C wo ein mageres schwarzes Mädchen,

D in der ein mageres schwarzes Mädchen,

descended from slaves and raised by a single mother

C das von Sklaven stammt und allein war mit seiner Mutter

D das von Sklaven abstammt, großgezogen von einer Mutter, die alleine stand,

can dream of becoming president

A 大統領になることを夢見ることができる

C träumen kann, Präsidentin zu werden

D doch träumen konnte, Präsident zu werden,

only to find herself reciting for one.

A 気づけば彼女は今 大統領のために詩を読んでいる

C um dann vor einem Präsidenten zu lesen.

D und nun hier steht, rezitierend für einen von ihnen.

And yes, we are far from polished,

A 私たちは完璧じゃないし ピカピカではないけれど

B 確かに、私たちは洗練されたものとは程遠く、純粋で無傷なものともほど遠い。しかし、私たちは完璧な共同体を目指しているわけではない。

C Und ja, wir sind gar nicht glatt,

D Und, gewiss, wir sind alles andre als geschliffen,

far from pristine,

A 完璧な国家を築くために 努力していないということではない

C wir sind nicht makellos,

D alles andre als makellos.

but that doesn’t mean

C aber das heißt nicht,

D Das aber heißt nicht,

we are striving to form a union that is perfect.

C dass wir eine Gemeinschaft formen wollen, die perfekt ist.

D dass wir uns mühten, eine Gemeinschaft zu schmieden, die perfekt ist.

We are striving to forge our union with purpose.

B 私たちは、目的のある共同体を目指しているのだ。

C Wir schmieden eine Gemeinschaft mit einem Ziel zusammen.

D Um eine Gemeinschaft vielmehr mühen wir uns, die Ziel hat und Zweck.

To compose a country, committed to all cultures, colors, characters, and conditions of man.

A 目的に向かって団結し どんな文化も肌色も特徴も状態も 受け入れる国をつくる

B あらゆる人の文化、肌の色、性格、状況を受け止められる国を作るために。

C Ein Land zusammenzubringen, für alle Kulturen, Farben, Temperamente, Bedingungen.

D Ein Land wollen wir bauen, das allen Kulturen verpflichtet ist, allen Farben, Charakteren und Weisen des Menschseins.

And so we lift our gaze, not to what stands between us

A だから私たちは上を向いて 私たちを隔てるものではなく 私たちに立ちはだかるものに目を向ける

B だからこそ、私たちの間に立ちはだかるものではなく、私たちの前に立ちはだかるものに目を向けよう。

C Und so heben wir unseren Blick, nicht auf das, was zwischen uns steht,

D Drum richten wir unsere Blicke nicht auf das, was zwischen uns,

but what stands before us.

C sondern auf das, was uns bevorsteht.

D auf das vielmehr, was vor uns steht.

We close the divide because we know to put our future first,

A 分断をなくす 未来を最優先するなら

B 分断を終わらせよう。なぜなら私たちは、未来を第一に考えるから。まずは、それぞれの違いに執着するのをやめなければならない。

C Wir schließen die Kluft, weil wir wissen, damit die Zukunft zuerst kommt,

D Wir überwinden, was trennt, wissen wir doch, was “Zukunft zuerst” verlangt,

we must first put our differences aside.

A 違いを超えなければならないから

C müssen wir erst beiseite tun, was uns trennt.

D nämlich alle Differenzen aus dem Weg zu räumen.

We lay down our arms

A 武器を置く そうすれば、その手を差し伸べることができるから

B 武器を置いて両手を広げよう。互いの手と手が届くように。

C Wir legen Waffen nieder,

D Drum senken wir die Waffen,

so we can reach out our arms

to one another.

C damit wir unsere Arme

nacheinander ausstrecken können.

D die Arme,

können Hände ausstrecken

allen anderen entgegen.

We seek harm to none and harmony for all.

A 誰も傷つけず皆が調和できるように

B 私たちは誰にも危害を加えない。すべての人のために、調和を求める。

C Wir streben nach Schaden für keinen und Harmonie für alle.

D Kein Leid, nicht Zwietracht, wir suchen Eintracht für alle.

Let the globe, if nothing else, say, this is true:

That even as we grieved, we grew.

A せめてこれは真実だと世界中に言わしめよう

悲しみながらも私たちは成長した

B せめて、これは真実だと世界に知らしめたい。

嘆きながらも、私たちは成長した。

C Lass die Welt, wenn nichts Anderes, sagen,

dass wir trauerten und daran wuchsen.

D Das, zumindest, soll wahr sein und gelten rund um die Welt:

Selbst wo wir trauerten, wuchsen wir.

That even as we hurt, we hoped.

A 傷ついても希望を捨てなかった

B 傷つきながらも、希望を抱いた

C Dass wir im Schmerz hofften.

D Selbst wo wir litten, hofften wir.

That even as we tired, we tried.

A 疲れても挑んだ私たちは永遠の絆で結ばれている

B 疲弊しながらも、挑戦した。

C Dass wir es in der Erschöpfung versuchten.

D Selbst wo wir müde wurden, mühten wir uns.

That we’ll forever be tied together, victorious.

A 勝利だと言えるように

B 私たちは永遠に結ばれ、勝利を手にするだろう。

C Dass wir für immer im Sieg miteinander verbunden sind.

D Dass wir für immer zusammenstehen. Siegreich.

Not because we will never again know defeat,

A 二度と敗北をしないためではなく

B これから先、もう二度と敗北しないからではない。

C Nicht weil wir nie wieder verlieren,

D Nicht, weil wir nie wieder Niederlagen erlitten.

but because we will never again sow division.

A 二度と分断の種をまかないために

B もう二度と、分断の種をまかないからだ。

C sondern weil wir nie wieder Zwietracht säen.

D Nein, weil wir nie wieder Trennung säen werden.

Scripture tells us to envision

A 誰もが平和で豊かに何も恐れることのない世界を 思い描こうと聖書は説く

B それぞれが自分のブドウの木やイチジクの木の下に座り、誰も恐れる必要のない世界を描くようにと、聖書は私たちに説いている。

C Die Schrift sagt uns, wir sollen erhoffen,

D Jeder, so lehrt uns die Schrift,

that everyone shall sit under their own vine and fig tree

C dass ein jeder sitze unterm eigenen Weinstock und Feigenbaum

D soll unter dem eigenen Weinstock, dem eigenen Feigenbaum sitzen.

and no one shall make them afraid.

C und niemand soll ihm Angst machen.

D Niemand soll jemandem Angst machen.

If we’re to live up to our own time,

A 私たちが今の時代に応えるなら

B 私たちの時代に適うとすれば、刃の中に勝利はない。私たちが架けてきた全ての橋にこそ、勝利がある。

C Wenn wir so leben, wie es unserer Zeit gebührt,

D Wollen wir erfüllen, was unsere Zeit verlangt,

then victory won’t lie in the blade, but in all the bridges we’ve made.

A 勝利は刃の中ではなく 私たちが築いたすべての橋にある

C dann liegt der Sieg nicht in unserem Schwert, sondern in den Brücken, die wir gebaut haben.

D dann wird der Sieg nicht im Schwert liegen, in all den Brücken vielmehr, die wir errichtet haben.

That is the promise to glade

A それが私たちがのぼる丘への約束 私たちに勇気があれば

B それが約束の地、私たちが恐れずにのぼろうとする丘だ。

C Das ist das Versprechen, das Tal der Freuden,

D Da ist das versprochene Licht,

The hill we climb.

C hinter dem Berg, auf den wir steigen.

D da der Hügel im Licht, den wir erklimmen,

If only we dare

C Wenn wir uns nur trauen.

D nur den Mut müssen wir finden.

It’s because being American is more than a pride we inherit.

A アメリカ人であることは 私たちが受け継いだ誇り以上のもの

B アメリカ人であるというのは、私たちが引き継ぐ誇り以上の意味がある

C Denn AmerikanerInnen zu sein ist mehr als ein Stolz, den wir erben.

D Amerikaner zu sein ist mehr als ein Stolz, den wir erben,

It’s the past we step into

A それは足を踏み入れた過去であり

B アメリカ人であるというのは、私たちが足を踏み入れた過去と、それをどう修復するかだ。

C Es ist die Vergangenheit, in die wir treten

D Vergangenheit vielmehr, die wir annehmen,

and how we repair it.

A いかに修復するかということ

C und wie wir sie flicken.

D ist das, was wir tun, sie zu heilen.

We’ve seen a force that would shatter or nation, rather than share it.

A 国を分かち合うより 粉々にしようとする力を見せつけられた

B 国を共有するどころか、粉砕してしまった力を私たちは見てきた。

C Wir haben eine Macht gesehen, die unsere Nation eher zerstören würde, als sie zu teilen.

D Wir haben eine Macht erlebt, die unsere Nation eher zerschlagen hätte, als Teil zu sein von ihr.

Would destroy our country if it meant delaying democracy.

A 国を壊し、民主主義を滞らせようとする試み

B それが民主主義を遅らせるものなら、私たちの国は滅びてしまう。

C Die das Land zerschlagen will, wenn sie dadurch Demokratie aufhält.

D Die unser Land zerstören würde, was denn sonst heißt: Demokratie auszubremsen.

And this effort very nearly succeeded.

A それは現実になりかけた

B あと少しで、滅びてしまうところだった。

C Und das hat fast funktioniert.

D Und um ein Haar wäre es geglückt.

But while democracy can be periodically delayed,

A 民主主義は一時的に止まることはあっても

B しかし、民主主義は一時的に止まることがあれど、

C Aber während sie Demokratie immer wieder aufhalten können,

D Demokratie lässt sich ausbremsen, eine Zeit lang,

it can never be permanently defeated.

A 敗北することは永久にない

B 永遠に敗北することはない。

C sie können sie nie auf Dauer besiegen.

D niemals jedoch vernichten auf Dauer.

In this truth,

A この事実、この信念のうちに

B この真実と信念をもってして、私たちは信じている。

C Auf diese Wahrheit,

D Auf diese Wahrheit;

in this faith we trust

C auf diesen Glauben vertrauen wir.

D diesen Glauben setzen wir.

For while we have our eyes on the future,

A しばし私たちは未来を見つめ

B 私たちが未来を見ているその時、

C Denn während wir unseren Blick auf die Zukunft heften,

D Denn solange wir unseren Blick auf die Zukunft richten,

history has its eyes on us.

A 歴史は私たちを見つめる

B 歴史は私たちを見ているから。

C hat die Geschichte uns im Blick.

D hat die Geschichte uns im Blick.

This is the era of just redemption.

A 今は贖罪の時代だ

B 今はまさに、償いの時代だ。

C Das ist die Zeit, in der wir erlöst werden.

D Dies aber ist die Zeit gerechter Erlösung.

We feared at its inception

A 私たちはその始まりに恐怖し

B はじめ、私たちは恐れていた。

C Wir haben am Anfang Angst gehabt,

D Angst hatten wir bei ihrem Anbruch,

We did not feel prepared to be the heirs

A このような恐ろしい時代を 受け継ぐ準備ができていないと感じていた

B そんな恐ろしい時代を引き継ぐ覚悟は、できていないように感じていたから。

C wir waren nicht vorbereitet darauf,

D fühlten uns nicht vorbereitet als Erben,

of of such a terrifying hour,

C solch eine schreckliche Zeit zu bekommen,

D Erben einer so furchtbaren Stunde.

but within it, we found the power

A しかし、その中で 私たちは新たな一章を記す力を見いだし

B そんな中でも、私たちは新たな章を書き上げ、希望と笑いを届ける力を見つけた。

C aber in ihr haben wir die Kraft gefunden

D Einmal eingetreten jedoch fanden wir die Kraft,

to author a new chapter.

C ein neues Kapitel zu schreiben.

D ein neues Kapitel zu schreiben,

To offer hope and laughter to ourselves.

A 自分たちに希望と笑いをもたらした

C Uns selber Hoffnung und Lachen zu schenken.

D Kraft, uns Hoffnung zu schenken und ein Lachen.

So while once we asked,

A どうしたら大惨事を乗り越えて 打ち勝つことができるかと 問うたこともあるが

B この破滅的な状況に、一体どう打ち勝てるのか。かつて私たちはそう思っていた。

C Und so, während wir zuerst gefragt haben,

D Wie, so fragten wir zuvor,

how could we possibly prevail over catastrophe?

C wie können wir diese Katastrophe nur überwinden,

D sollten wir diese Katastrophe je überstehen,

Now we assert

A 今は大惨事が私たちを乗り越えて 打ち勝つはずがないと断言できる

B でも今、こう宣誓できる。この壊滅的な状況は、果たして私たちに打ち勝てるか?

C so behaupten wir jetzt,

D sind jetzt aber sicher:

how could catastrophe possibly prevail over us?

C wie könnte diese Katastrophe uns nur überwinden?

D Wie denn sollte diese Katastrophe uns überstehen?

We will not march back to what was,

A 私たちは過去には戻らず

B 私たちは過去に戻るのではなく、未来に進む。

C Wir marschieren nicht dorthin zurück, wo wir herkommen,

D Zurück zu dem, was war, gehen wir nicht.

but move to what shall be

a country that is bruised but whole

benevolent, but bold,

fierce, and free.

A 未来に歩みを進める

国は傷を負っているが

一体となって

慈悲深いが勇敢で、力強く、自由だ

B 傷つきながらも一体となっていて、優しくも大胆で、力強く自由な国へと。

C sondern bewegen uns weiter

in Richtung auf ein Land, das verletzt ist, aber ganz,

gütig, aber mutig,

wild und frei.

D Gehen zu auf das, was sein wird.

Ein Land, verletzt zwar, doch noch beisammen,

ein Land behütend, doch kühn,

glühend und frei

We will not be turned around

A 私たちは脅しに振り回されたり

B 私たちは脅しによって引き戻されたり、

C Wir werden uns nicht umdrehen lassen

D Wir werden uns nicht umdrehen,

or interrupted by intimidation

A 邪魔されたりしない

B 邪魔されたりはしない。

C oder unterbrechen durch Einschüchterung,

D nicht aufhalten lassen durch Drohung.

because we know our inaction and inertia

A 何もしないことや 惰性で動くことが 次の世代に引き継がれ 未来となることを知っているから 私たちの失敗が次の世代の重荷になる

B なぜなら、私たちの不実行性や惰性が次の世代に引き継がれ、それが未来になることを知っているから。

C weil wir wissen, wenn wir nicht handeln und träge bleiben,

D Denn das wissen wir: unsere Tatenlosigkeit, unsere Trägheit

will be the inheritance of the next generation.

B 私たちの失敗は、次の世代の重荷になる。

C dann geben wir’s weiter an die nächste Generation.

D wäre das Erbe derer, die nach uns kommen.

Our blunders become their burdens,

C Unsere Fehler werden zu ihren Lasten,

D Unsere Fehler ihre Last.

but one thing is certain.

A ただ1つだけ確かなことがある

B でもひとつ、確かなことがある。

C aber eines ist klar:

D Eines aber ist gewiss:

If we merged mercy with might,

A 慈悲と力、力と正義が融合されれば

B 慈悲と権力を、権力と権利を私たちが融合させれば、

C Wenn wir Mitleid und Stärke verbinden,

D Verbinden wir Mitgefühl mit Macht

and might with right,

C und Stärke mit Recht,

D und Macht mit Recht,

then love becomes our legacy, and change our children’s birthright.

A 博愛こそが私たちの遺産となり 変革こそ子どもたちの生まれながらの権利になる

B 愛が私たちの遺産になる。そして、私たちの子どもたちが生まれ持って得るものが変わるだろう。

C dann wird Liebe zu unserm Erbe, und Wandel wird zum Geburtsrecht unserer Kinder.

D wird Liebe zu unsrem Vermächtnis und Veränderung zum Geburtsrecht unserer Kinder.

So let us leave behind a country

A だから私たちは 受け継いだ国よりも良い国を残そう

B だから、私たちに残された国よりも良い国を残そうではないか。

C So lasst uns ein Land hinterlassen,

D Lasst uns ein Land übergeben

better than the one we were left with

C das besser ist, als was man uns hinterlassen hat.

D das besser ist als das, das man uns überließ.

Every breath, my bronze-pounded chest.

A 高鳴る胸で呼吸するたびに

B ブロンズ色の私の胸が呼吸をするたび、

C Mit jedem Atem, meine bronzene Brust.

D Jeder Atemzug meiner bronze-gestählten Brust,

We will raise this wounded world into a wondrous one.

A 傷ついた世界を素晴らしき世界に変える

B 私たちは傷ついたこの世界を素晴らしいものへと変えていく。

C Wir erheben diese verwundete Welt zu einer wunderbaren.

D und wir werden diese verwundete Welt zur wunderschönen machen.

We will rise from the gold-limbed hills of the West.

A 私たちは西部の黄金の丘から立ち上がる

B 黄金の丘がある西の地から、私たちは立ち上がる。

C Wir stehen auf aus goldgliedrigen Hügeln des Westens.

D Erheben werden wir uns von den goldgliedrigen Hügeln des Westens.

We will rise from the windswept Northeast

A 祖先が革命を実現させた 風が吹き荒れる北東の地から立ち上がる

B 私たちの祖先が最初に革命を実現させたあの吹きさらしの北東の地から、私たちは立ち上がる。

C Wir stehen auf aus dem windgepeitschten Nordosten,

D Erheben werden wir uns im windgepeitschten Nordosten,

where our forefathers first realized revolution.

C wo unsere Vorfahren zuerst Revolution wahr gemacht haben.

D wo unseren Vorfahren zuerst die Revolution gelang.

We will rise from the lake-rimmed cities of the midwestern states.

A 湖に囲まれた中西部の町から立ち上がる

B 湖畔の街に囲まれた中西部の地から、私たちは立ち上がる。

C Wir stehen auf aus den Städten an Seen im Mittleren Westen.

D Erheben werden wir uns in den seengesäumten Städten des mittleren Westens.

We will rise from the sunbaked South.

A 太陽が照りつける南部から立ち上がる

B 日が照る南の地から、私たちは立ち上がる。

C Wir stehen auf aus dem sonnenverbrannten Süden.

D Erheben im sonnendurchglühten Süden.

We will rebuild, reconcile and recover

A 私たちは再建し、和解し、回復する

B 私たちは再建し、和解し、回復する。

C Wir bauen wieder auf, versöhnen, erneuern

D Aufbauen werden wir, versöhnen, wieder gesunden,

and every known nook of our nation.

A 国と呼ばれる、あらゆる場所で

B そして、私たちの国の隅という隅まで、

C jedes Eck, das jemand kennt an unserer Nation.

D und zwar jeden bekannten Winkel unserer Nation,

And every corner called our country.

C Und jede Ecke, die man unsere Nation nennt.

D jede Ecke, die unser Land genannt wird.

Our people diverse and beautiful will emerge,

A 多様で美しい人々が立ち上がる 打ちのめされても美しい人々が

B 多様で美しい国民が現れるだろう。打ちのめされて、それでも美しい姿で。

C Unser Volk so verschieden und schön kommt hervor,

D Und unser Volk wird sichtbar werden, so vielfältig und schön,

battered and beautiful.

C angeschlagen und schön.

D so angeschlagen und dennoch schön.

When day comes, we step out of the shade

A 一日が始まるとき

B 夜が明ける時、私たちは臆することなく、炎の影から一歩踏み出す。

C Wenn der Tag kommt, treten wir aus dem Schatten,

D Der Tag wird kommen, und wir treten heraus aus dem Schatten,

aflame and unafraid

A 私たちは真っ赤な炎のように輝き 恐れることなく暗がりから抜け出す

C entflammt und ohne Furcht.

D entflammt und ohne Furcht.

The new dawn blooms as we free it.

A 私たちが解き放てば、新たな夜明けは花開く

B 私たちが解放すれば、夜明けはどんどん膨らんでいく。

C Die Morgendämmerung blüht, wenn wir sie freilassen.

D Der neue Morgen strahlt, wenn wir ihn befreien.

For there was always light.

A 光はいつもそこにある

B 光はいつもそこにある。

C Denn da war immer Licht,

D Denn immer ist Licht,

If only we’re brave enough to see it.

A 私たちにそれを見る勇気があれば

B 私たちに、光を見る勇気があれば。

C wenn wir nur mutig genug sind, es zu sehen,

D wenn wir nur mutig genug sind, es zu sehen,

If only we’re brave enough to be it.

A 私たちに光になる勇気があれば

B 私たちが、光になる勇気があれば。

C wenn wir nur mutig genug sind, es zu sein.

D nur mutig genug, es zu sein.

The Story Behind TIME’s Amanda Gorman Cover

Amanda Gorman’s eloquent poetry at Joe Biden’s presidential Inauguration soothed many Americans still reeling just two weeks after pro-Trump supporters staged an insurrection at the Capitol.

“We will rebuild, reconcile and recover

and every known nook of our nation

and every corner called our country,

our people diverse and beautiful will emerge,

battered and beautiful.”

This week, Gorman—the youngest Inaugural poet in U.S. history—is featured on TIME’s cover, where the 22-year-old wears a bright yellow familiar from January’s event.

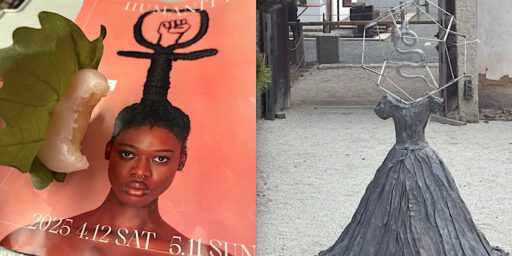

Conceptual artist Awol Erizku captured Gorman for TIME in what he hoped would be a “very timely arrival portrait.”

“I was interested in allowing her to own the space that she’s in right now,” Erizku says. “We were going for timelessness, something that felt classical” and tied in to the “resurgence of a Black renaissance.”

Awol Erizku’s portrait of Gorman is an “indirect nod” to Maya Angelou. “It needed a layer of depth that only poetry can explain,” he says. “I was interested in allowing her to own the space that she’s in right now.”

It was a special moment for him, too. “Like many who witnessed the recent presidential Inauguration, I was captivated by her poem and her exquisite delivery,” says Erizku, who is based in Los Angeles and has exhibited at institutions including New York City’s Museum of Modern Art and the Studio Museum in Harlem. “For TIME, I wanted to extricate her from the political dimension and immerse it in a more cosmic atmosphere to add to the weight of her words.”

In a separate image featured inside the magazine, Gorman holds a white birdcage in a nod to the birdcage ring she wore on inauguration day. (That ring was a gift from Oprah, referring to previous inauguration poet Maya Angelou’s poem, “I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings.”)

“It needed a layer of depth that only poetry can explain,” Erizku says of the image.

A team of Black creative professionals prepared Gorman for the portraits: Jason Bolden styled her, Autumn Moultrie did her makeup, Khiry provided jewelry and the dress was from Greta Constantine.

The magazine package also features typography from Tré Seals, the founder of Vocal Type foundry, who specializes in making type inspired by communities of color and social justice movements. “When a singular perspective dominates an industry, regardless of any advancements in technology, there can be (and has been) only one way of thinking, teaching and creating,” Seals says. His bold, declarative typography, in a font called Neue Black, opens the package with its defining statement: “THE RENAISSANCE IS BLACK.”

up-date 2021/3/2

‘Shocked by the uproar’: Amanda Gorman’s white translator quits

Mon 1 Mar 2021

International Booker winner Marieke Lucas Rijneveld will not translate inaugural poet’s work into Dutch after anger that a Black writer was not hired

The acclaimed author Marieke Lucas Rijneveld has pulled out of translating Amanda Gorman’s poetry into Dutch, after their publisher was criticised for picking a writer for the role who was not also Black.

Dutch publisher Meulenhoff had announced Rijneveld, winner of the International Booker prize, as the translator of the Joe Biden inaugural poet’s forthcoming collection, The Hill We Climb, last week. But the move quickly drew opprobrium. Journalist and activist Janice Deul led critics with a piece in Volkskrant asking why Meulenhoff had not chosen a translator who was, like Gorman, a “spoken-word artist, young, female and unapologetically Black”.

“An incomprehensible choice, in my view and that of many others who expressed their pain, frustration, anger and disappointment via social media,” wrote Deul. “Isn’t it – to say the least – a missed opportunity to [have hired] Marieke Lucas Rijneveld for this job? They are white, nonbinary, have no experience in this field, but according to Meulenhoff are still the ‘dream translator’?”

Rijneveld had previously welcomed the assignment, saying that “at a time of increasing polarisation, Amanda Gorman shows in her young voice the power of spoken word, the power of reconciliation, the power of someone who looks to the future instead of looking down”. But in a statement, they subsequently announced their withdrawal from the project.

“I am shocked by the uproar surrounding my involvement in the spread of Amanda Gorman’s message and I understand the people who feel hurt by Meulenhoff’s choice to ask me,” Rijneveld wrote. “I had happily devoted myself to translating Amanda’s work, seeing it as the greatest task to keep her strength, tone and style. However, I realise that I am in a position to think and feel that way, where many are not. I still wish that her ideas reach as many readers as possible and open hearts.”

Meulenhoff said it was Rijneveld’s decision to resign, and that Gorman, who is 22, had selected the 29-year-old herself, as a fellow young writer who had also come to fame early. “We want to learn from this by talking and we will walk a different path with the new insights,” said the publishing house’s general director Maaike le Noble. “We will be looking for a team to work with to bring Amanda’s words and message of hope and inspiration into translation as well as possible and in her spirit.”

“Thank you for this decision,” Deul wrote on Twitter.

Gorman, the first national youth poet laureate in the US, gave a tour-de-force performance of her poem The Hill We Climb at Biden’s January inauguration, hailed by names from Michelle Obama to Oprah Winfrey. Her forthcoming books, The Hill We Climb and children’s book Change Sings, subsequently shot to the top of book charts.

up-date 2021/3/28

Amanda Gorman’s poetry united critics. It’s dividing translators.

Hadija Haruna-Oelker, a Black journalist, has just produced the German translation of Amanda Gorman’s “The Hill We Climb,” the poem about a “skinny Black girl” that for many people was the highlight of President Joe Biden’s inauguration.

So has Kübra Gümüsay, a German writer of Turkish descent.

As has Uda Strätling, a translator, who is white.

Literary translation is usually a solitary pursuit, but German publisher Hoffmann und Campe went for a team of writers to ensure the translation of Gorman’s poem — just 710 words — wasn’t just true to Gorman’s voice. The trio was also asked to make its political and social significance clear and to avoid anything that might exclude people of color, people with disabilities, women or other marginalized groups.

“It was a gamble,” Strätling said of the collaborative approach.

For nearly two weeks, the team debated word choices, occasionally emailing Gorman for clarifications. But as they worked, an argument was brewing elsewhere in Europe about who has the right to translate the poet’s work.

“This whole debate started,” Gümüsay said, with a sigh.

It began in February when Meulenhoff, a publisher in the Netherlands, said it had asked Marieke Lucas Rijneveld, a writer whose debut novel won last year’s Booker International Prize, to translate Gorman’s poem into Dutch.

Rijneveld was the “ideal candidate,” Meulenhoff said in a statement. But many social media users disagreed, asking why a white writer had been chosen when Gorman’s reading at the inauguration had been a significant cultural moment for Black people.

Three days later, Rijneveld quit. (Rijneveld declined an interview request for this article.)

In March, the debate reignited after Victor Obiols, another white translator, was dropped by the Catalan publisher Univers. Obiols said he was told his profile “was not suitable for the project.” (A Univers spokeswoman declined to comment.)

Literary figures and newspaper columnists across Europe have been arguing for weeks about what these decisions mean, turning Gorman’s poem into the latest flash point in debates about identity politics across the continent. The discussion has shone a light on the often unexamined world of literary translation and its lack of racial diversity.

“I can’t recall a translation controversy ever taking the world by storm like this,” Aaron Robertson, a Black Italian-to-English translator, said in a phone interview.

“This feels something of a watershed moment,” he added.

On Monday, the American Literary Translators Association waded into the furor. “The question of whether identity should be the deciding factor in who is allowed to translate whom is a false framing of the issues at play,” it said in a statement published on its website.

The real problem underlying the controversy was “the scarcity of Black translators,” it added. Last year, the association carried out a diversity survey. Only 2% of the 362 translators who responded were Black, a spokeswoman for the association said in an email.

In a video interview, the members of the German team said they, too, felt the debate had missed the point. “People are asking questions like, ‘Does color give you the right to translate?’” Haruna-Oelker said. “This is not about color.”

She added: “It’s about quality, it’s about the skills you have, and about perspectives.” Each member of the German team brought different things to the group, she said.

The team spent a long time discussing how to translate the word “skinny,” without conjuring images of an overly thin woman, Gümüsay said, and they debated how to bring a sense of the poem’s gender-inclusive language into German, in which many objects — and all people — are either masculine or feminine. “You’re constantly moving back and forth between the politics and the composition,” Strätling said.

“To me it felt like dancing,” Gümüsay said of the process. Haruna-Oelker added that the team tried hard to find words “which don’t hurt anyone.”

But whereas the German translators were happy to engage with the identity politics, others expressed frustration at the translator departures and their implications. Nuria Barrios, the translator of the poem’s Spanish edition, who is white, wrote in the newspaper El País that Rijneveld’s stepping down from the project was “a catastrophe.”

“It is the victory of identity politics over creative freedom,” she wrote, adding: “To remove imagination from translation is to subject the craft to a lobotomy.”

Some Black academics and translators have also expressed concern. “There is a tacit idea that we are supposed to be especially concerned about the ‘appropriateness’ of a translator’s identity in the particular case of blackness,” John McWhorter, a professor of English and comparative literature at Columbia University, said in an email.

Other differences between writers and their translators — such as wealth levels, or political views — were not sparking concern, McWhorter added. “Instead, our sense of ‘diversity’ is narrower than that word implies: It’s only about skin color,” he said.

Couching the discussion in terms of appropriateness was “really ridiculous,” said Janice Deul, a Black Dutch journalist and activist who on Feb. 25 wrote an opinion piece for De Volkskrant, a Dutch newspaper, calling Rijneveld’s appointment “incomprehensible.” The following day, Rijneveld resigned.

“This is not about who can translate, it’s about who gets opportunities to translate,” Deul said. She listed 10 Black Dutch spoken-word artists who could have done the job in her article but said all of them had been overlooked.

The one opinion missing in all of this is, of course, Gorman’s. Viking is releasing “The Hill We Climb” in the United States on Tuesday. Apple TV Plus on Friday began streaming her interview with Oprah Winfrey, but she has not commented on the debate her work has spurred. Her spokeswoman didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Gorman, or her agent, Writers House, which represents the translation rights, appeared to have influence on who was selected. Aylin LaMorey-Salzmann, the editor of the German edition of “The Hill We Climb,” said that the rights owner had to agree to the choice, which had to be someone of similar profile to Gorman.

Irene Christopoulou, an editor at Psichogios, the poem’s Greek publisher, was still waiting for approval for its choice of translator. The translator was a white “emerging female poet,” Christopoulou said in an email. “Due to the racial profile of the Greek population, there are no translators/poets of color to choose from,” she added.

A spokeswoman for Tammi, the poem’s Finnish publisher, said in an email that “The negotiations are still going on with the agent and Amanda Gorman herself.”

Several European publishers named Black musicians as their translators. Timbuktu, a rapper, has completed a Swedish version, and Marie-Pierra Kakoma, a singer better known as Lous and the Yakuza, has translated the French edition, which will be published by Editions Fayard in May.

“I thought Lous’ writing skills, her sense of rhythm, her connection with spoken poetry would be tremendous assets,” Sophie de Closets, a publisher at Fayard, said in an email explaining why she chose a pop star.

Issues of identity “should definitely be considered” when hiring translators, de Closets added, but that went beyond race. “It is the publisher’s responsibility to look for the ideal combination between one given work and the person who will translate it,” she said.

Haruna-Oelker, one of the German translators, said one disappointing outcome of the debate in Europe was it had diverted attention from the message of Gorman’s poem. “The Hill We Climb” spoke about bringing people together, Haruna-Oelker said, just as the German publisher had done by assembling a team.

“We’ve tried a beautiful experiment here, and this is where the future lies,” Gümüsay said. “The future lies in trying to find new forms of collaboration, trying to bring together more voices, more sets of eyes, more perspectives to create something new.”

https://artdaily.cc/news/134289/Amanda-Gorman-s-poetry-united-critics–It-s-dividing-translators-#.YGBvXC2B2Rs

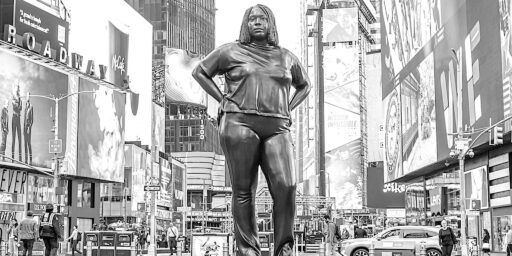

up-date 2021/9/15

Amanda Gorman reimagines the Statue of Liberty, wearing Vera Wang for the Met Gala 2021. Her gorgeous gown reportedly features more than 3,000 individually hand-stitched crystals.