ゲニウス・ロキを巡って、エゴン・シーレ vs 亜 真里男 Genius loci: Egon Schiele vs Mario A

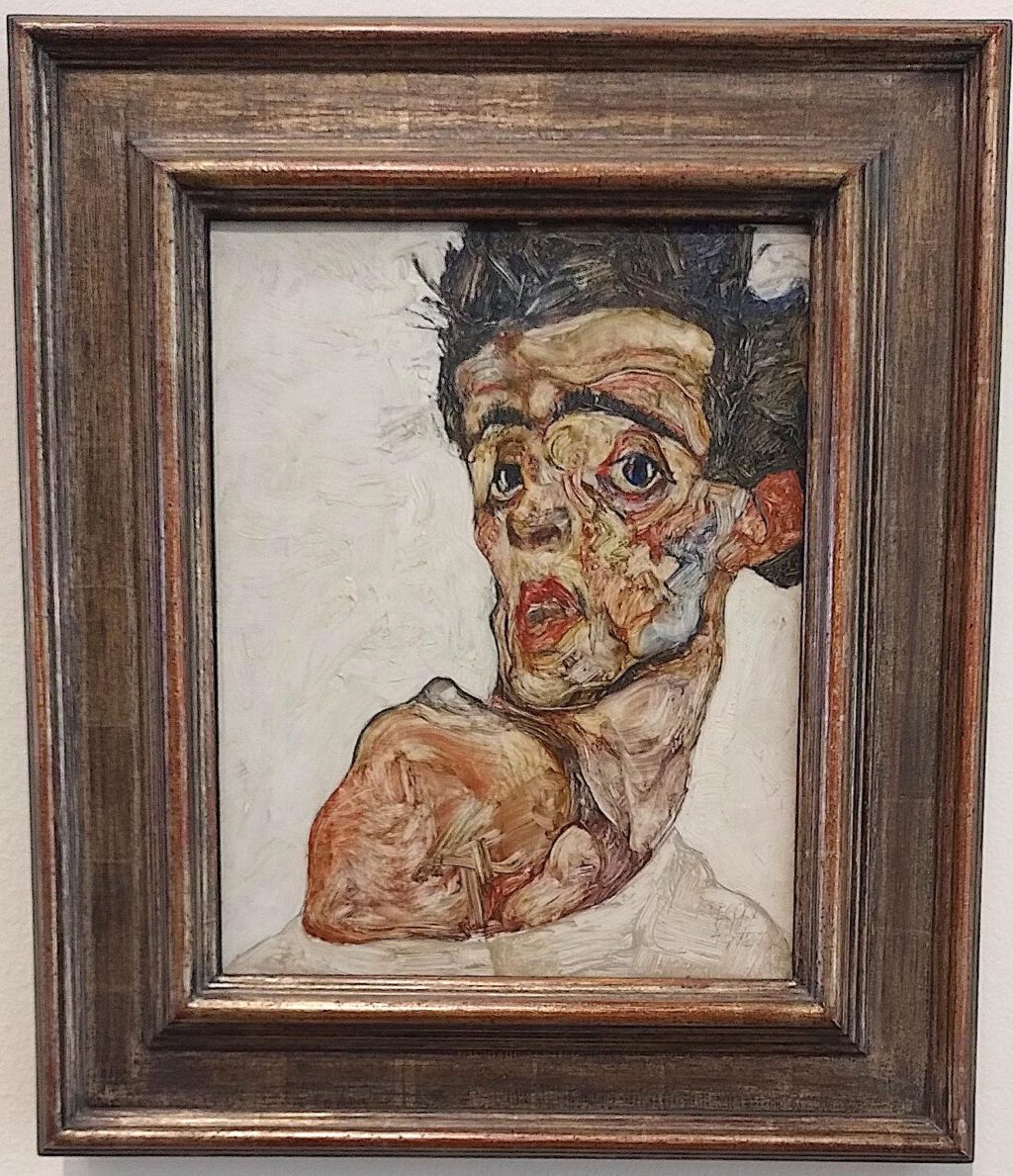

I develop strong emotional feelings to every artist who creates or reflects “la condizione umana”. In addition to Hans Bellmer or Otto Dix or Pierre Bonnard, Egon Schiele is also among my “genius loci”. Namely more about the ‘mental space’, in which their works occupy my brain, make me think, elaborate. It has been proven that there are numerous parallels between me and Egon Schiele. To write down an analytical art criticism of Egon Schiele’s Gesamtkunstwerk here would be presumptuous, since excellent texts have already been written worldwide.

See for example:

http://www.egon-schiele-jahrbuch.at/images/pdf/EGON%20SCHIELE%20JAHRBUCH,%20Band%20I,%202011.pdf

It would also go beyond the scope of the ART+CULTURE concept.

My attentive ART+CULTURE readers know about my artworks, consequently a bridge to Egon Schiele is mentally established. This associative curatorial practice on ART+CULTURE naturally involves a new form of perception, as I often track down unknown works and add them here. A luxury art experience that costs the reader no money. In the contemporary context, I try to introduce the artist personally.

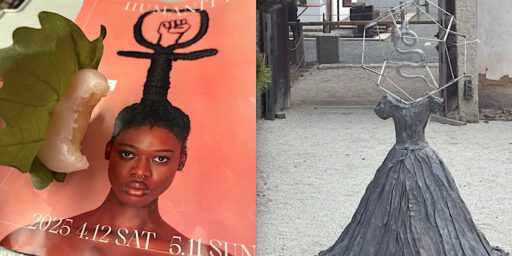

On the basis of my Japan-related artistic practice, a new perspective on Schiele’s can be opened, precisely because we both possess similar, analytical perspectives regarding humanity. Not to overuse the word “genius loci”, because it implies also the artist’s habitat: Schiele = Vienna, Me = Tokyo, I also find affinities to the concept of “spiritus loci”. Here, the mental leap, the connotation associated with the Japanese contemporary elitist art center can be pretty easily noticed.

On the human scale, for the artist it’s more or less about survival in a foreign but cosmopolitan, expensive Megapolis, which embodies the paradox allure of Contemporary Chaotic Charming Tokyo.

The existential, philosophical relationship between me and Japan, which one has grown fond of.

Since as a “Japanese” artist (nota bene: an artist from Japan) I also carry 500 years of “European” oil painting history on my shoulders, the scope of my influential work takes on a fateful component of Japanese art history.

Me, being part of Japanese art history.

May I quote art critic ICHIHARA Kentaro “Mario A. An Artist of Japan as an Eternal Revolutionary” and the late art critic NAGOYA Satoru “Mario A, one of the most brilliantly gifted–or perhaps I should say, the single most brilliantly gifted––oil painting artist in Japan”.

美術批評家 市原研太郎 「マリオ・A 永久革命家としての日本のアーティスト」,

美術批評家 名古屋覚により「日本で最も優れた油彩を制作する画家の一人、いや唯一の一人」.

In this context, the allegorical comparison to the above mentioned artists helps. The love towards Japonisme, the love about oil painting, the respectful love and appreciation of the (complicated) Human Experience. Monocausalities are deliberately scrambled to create a tension.

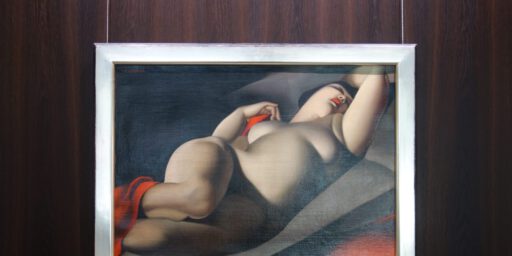

The artist embedded in self-consciousness. With all imaginable philosophical facets, innate sensuality, affectionate transference and eroticism included.

This is me. This is what I create.

Tokyo 2023

Mario A 亜 真里男

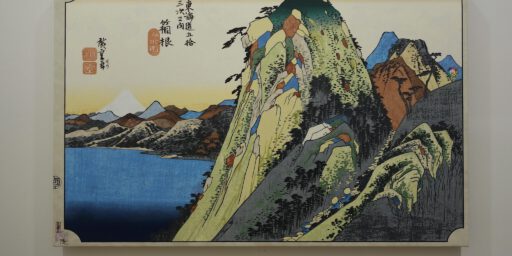

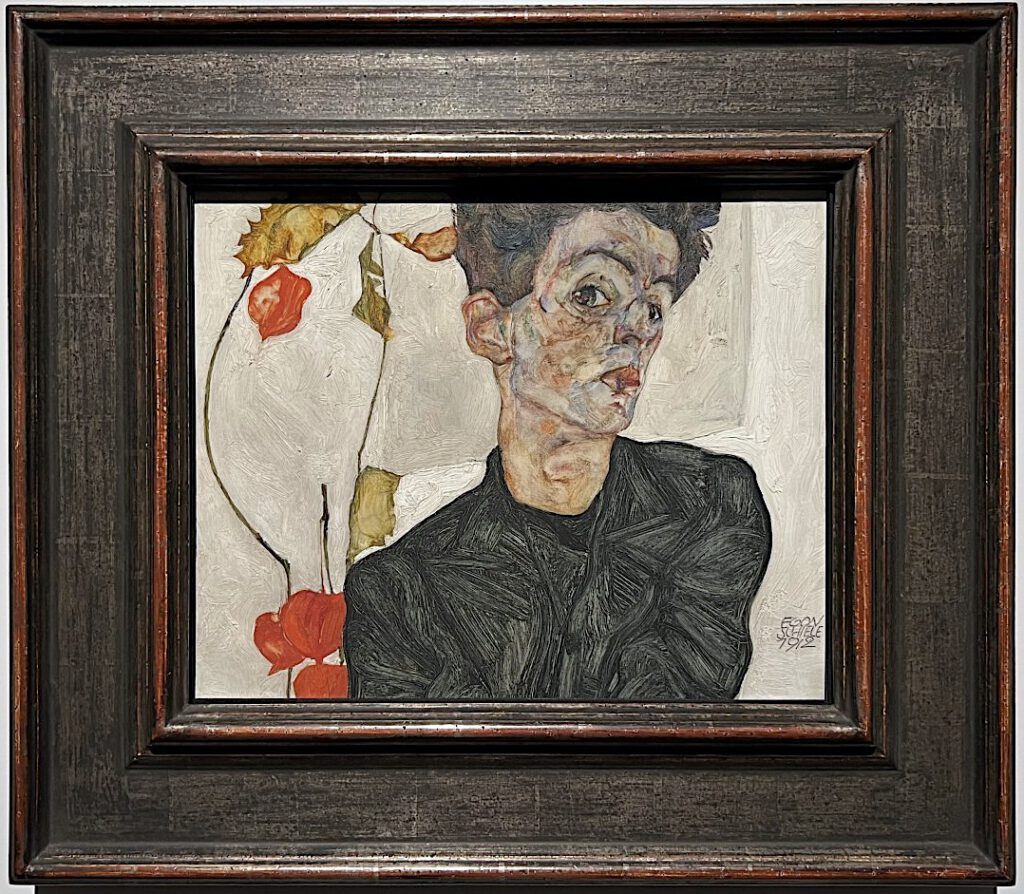

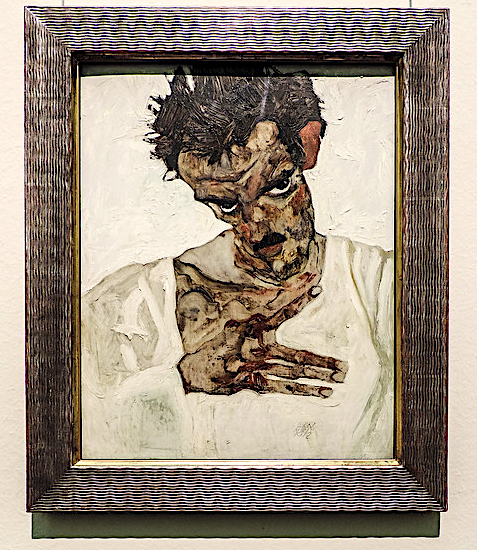

Egon Schiele “Self-Portrait with Chinese Lantern Plant” 1912, Oil, opaque color on wood, 32.4 x 40.2 cm

Egon Schiele “Stylised Flowers in Front of a Decorative Background” 1908, oil, gold and silver pigments

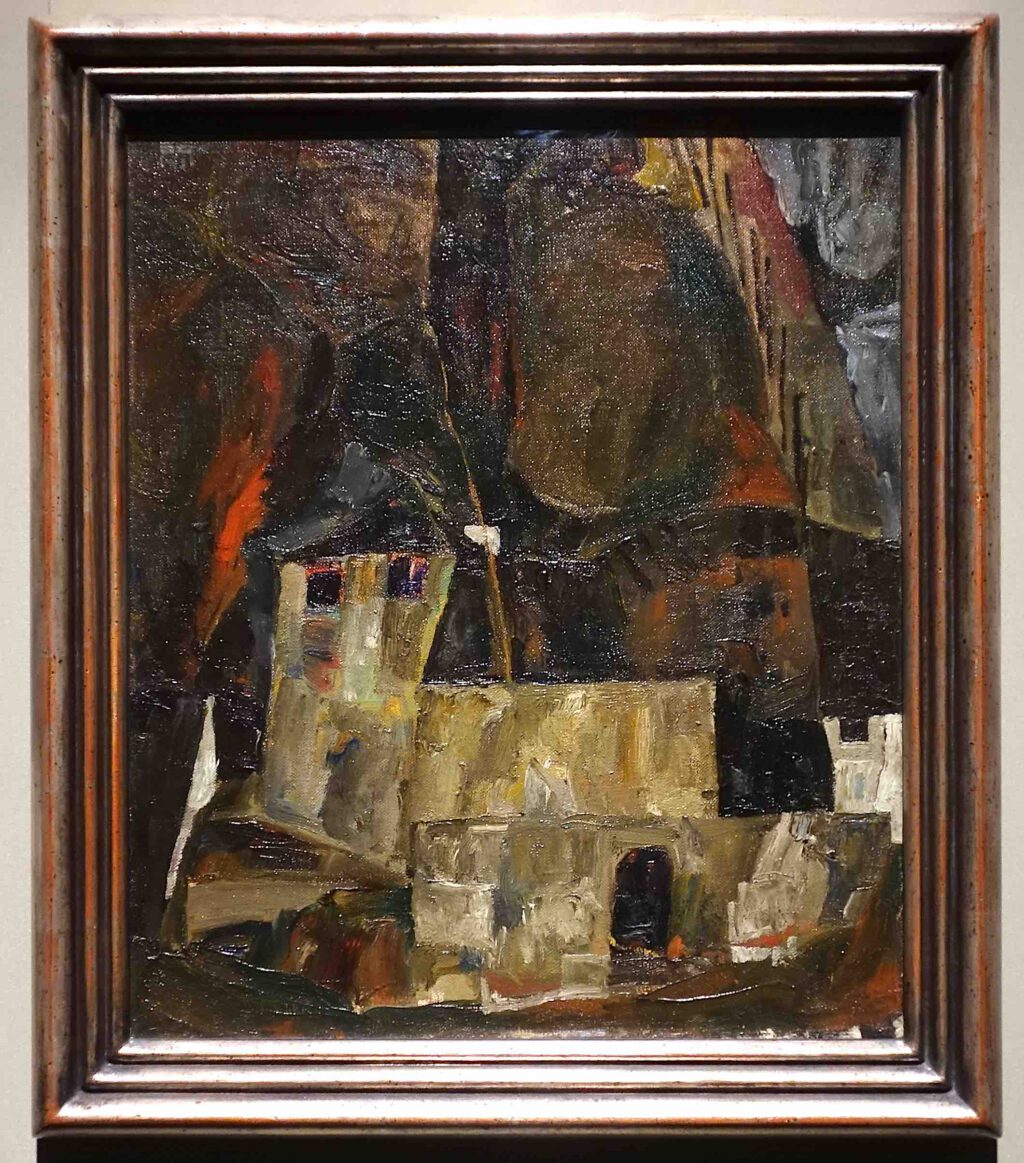

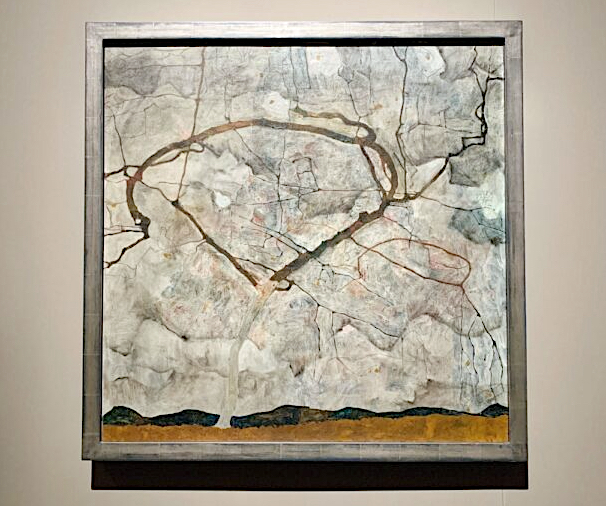

Egon Schiele “House and Wall in Hilly” 1911, oil on canvas

Egon Schiele “Mutter mit Kind” 1912, Öl auf Leinwand

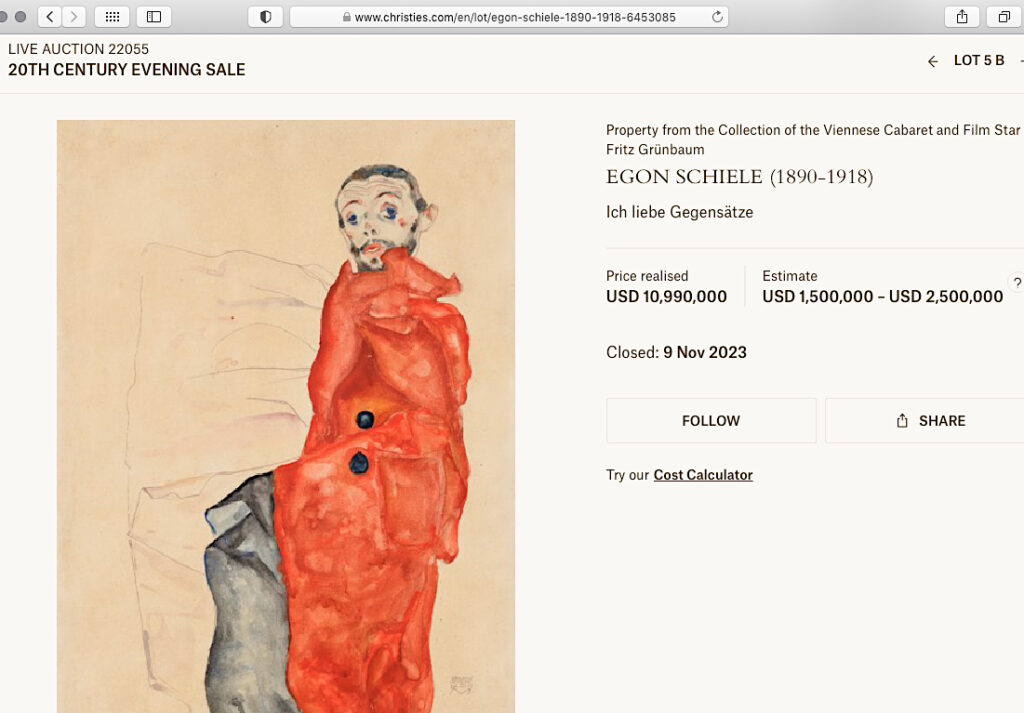

up-date 2023/11/10

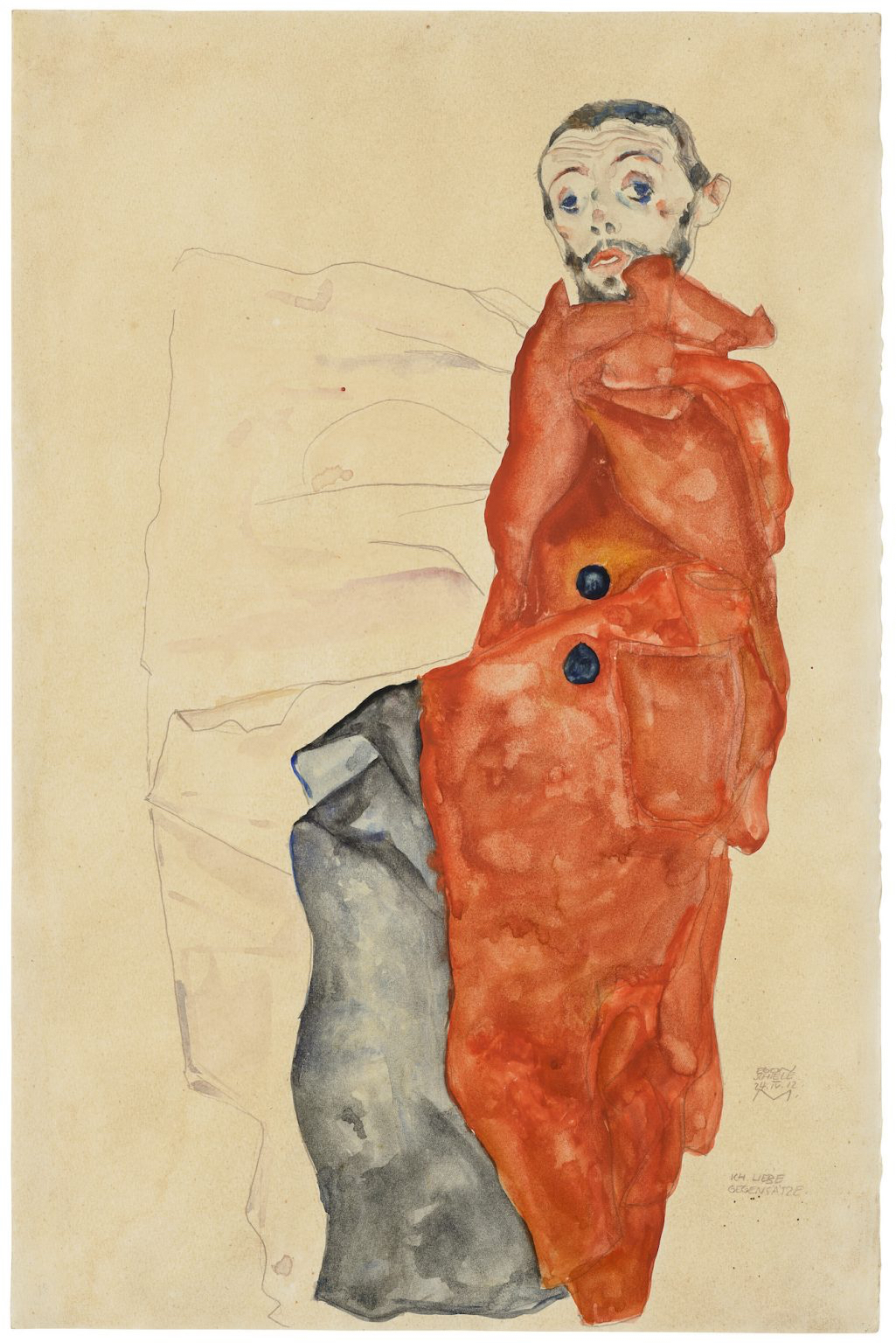

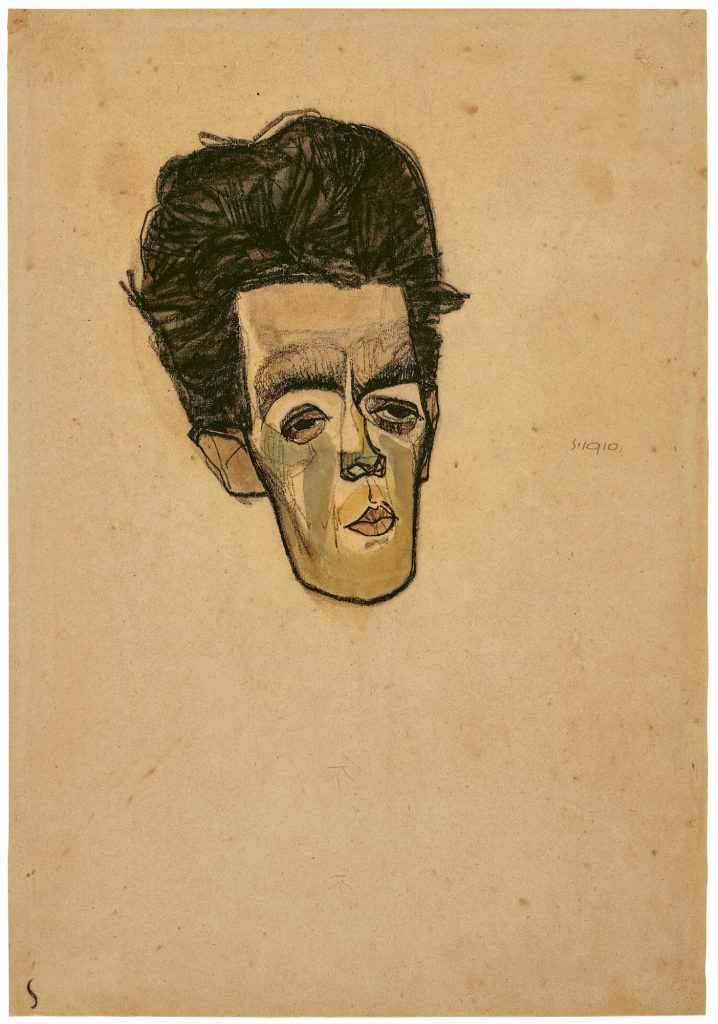

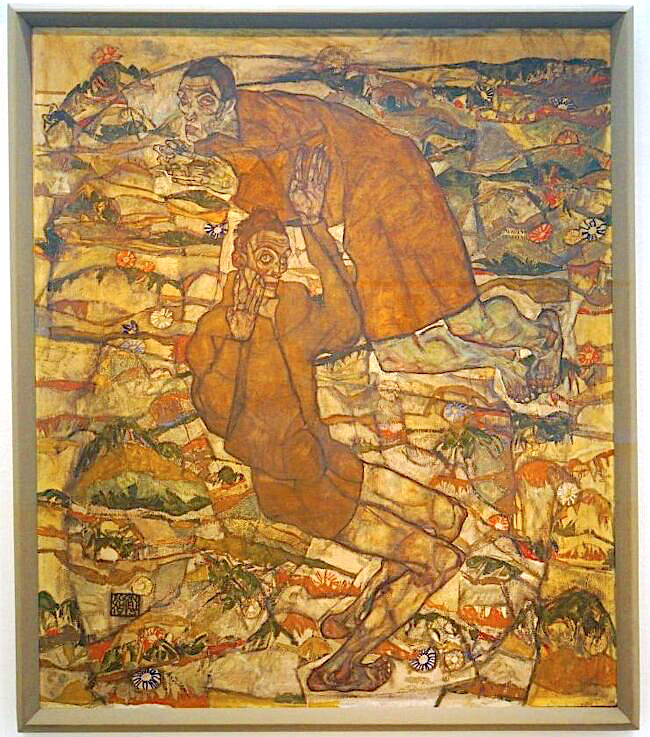

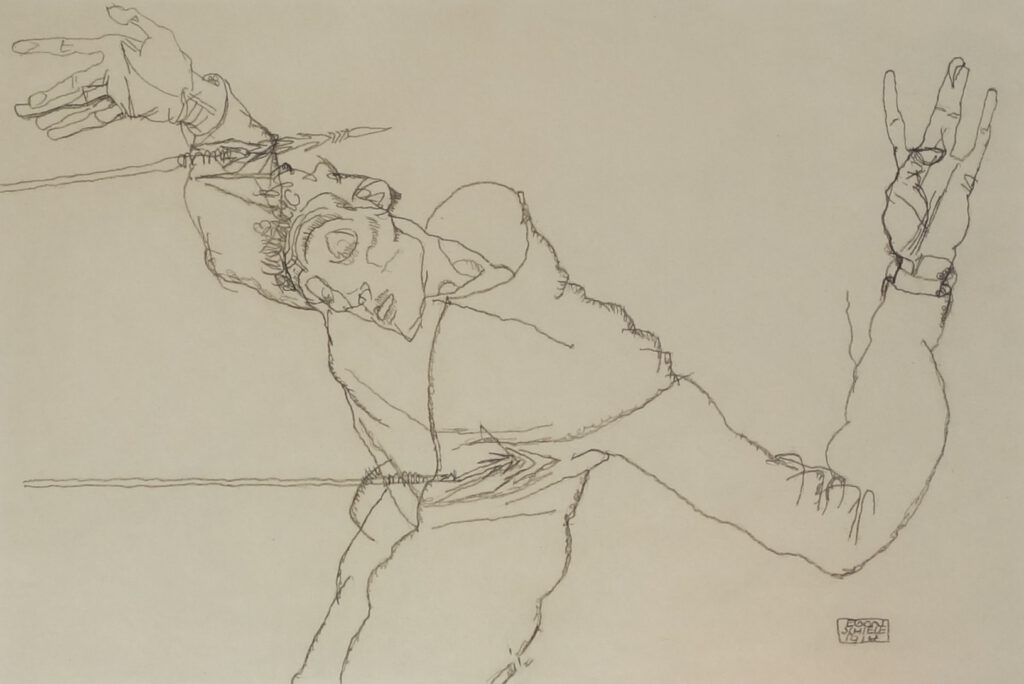

LIVE AUCTION 22055

20TH CENTURY EVENING SALE

LOT 5 B

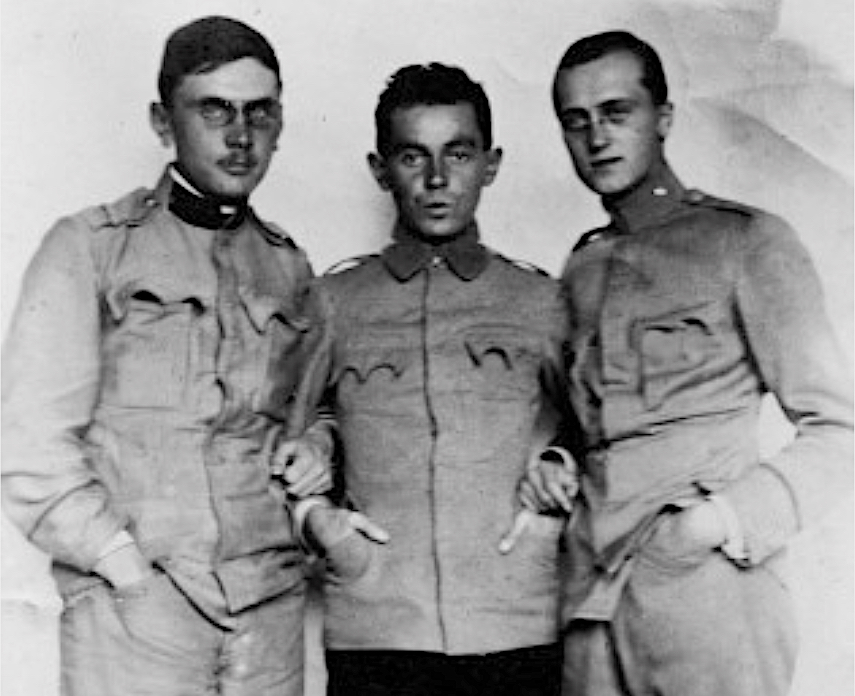

Property from the Collection of the Viennese Cabaret and Film Star Fritz Grünbaum

EGON SCHIELE (1890-1918)

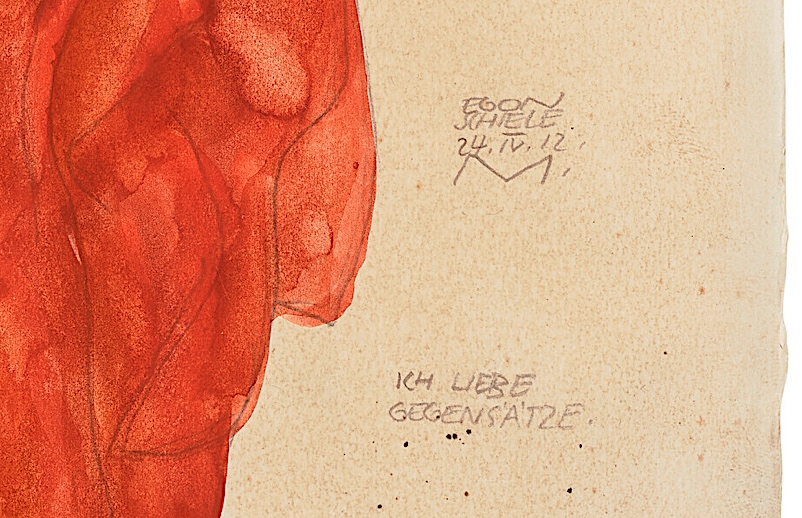

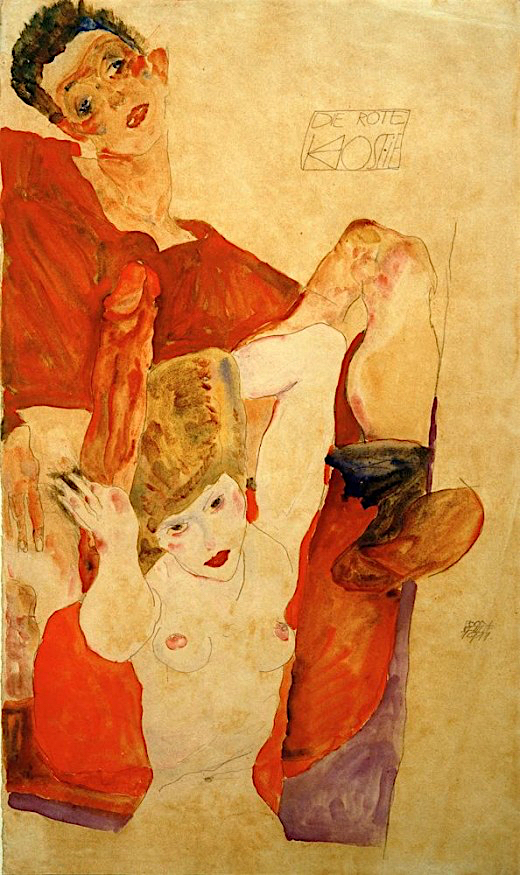

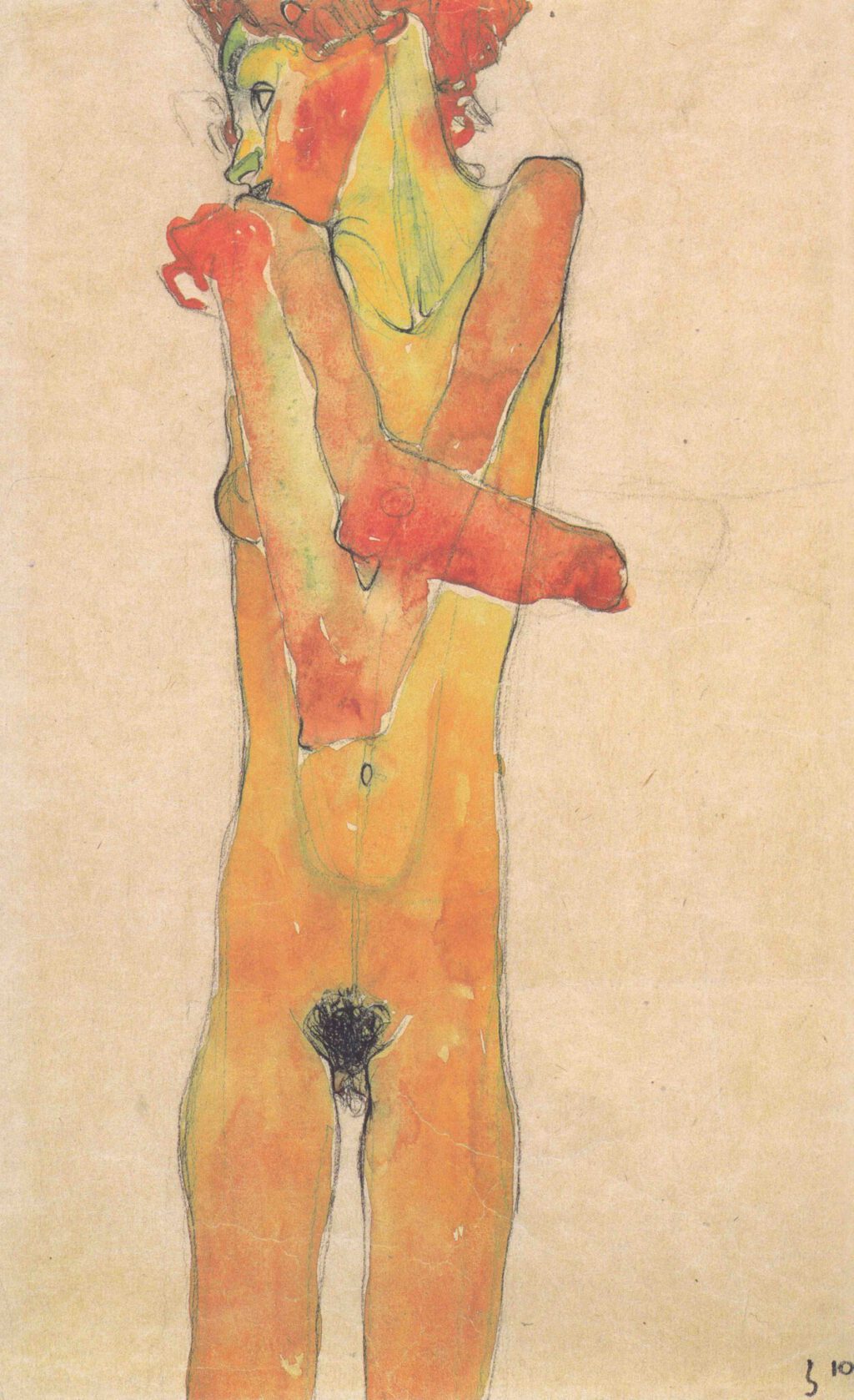

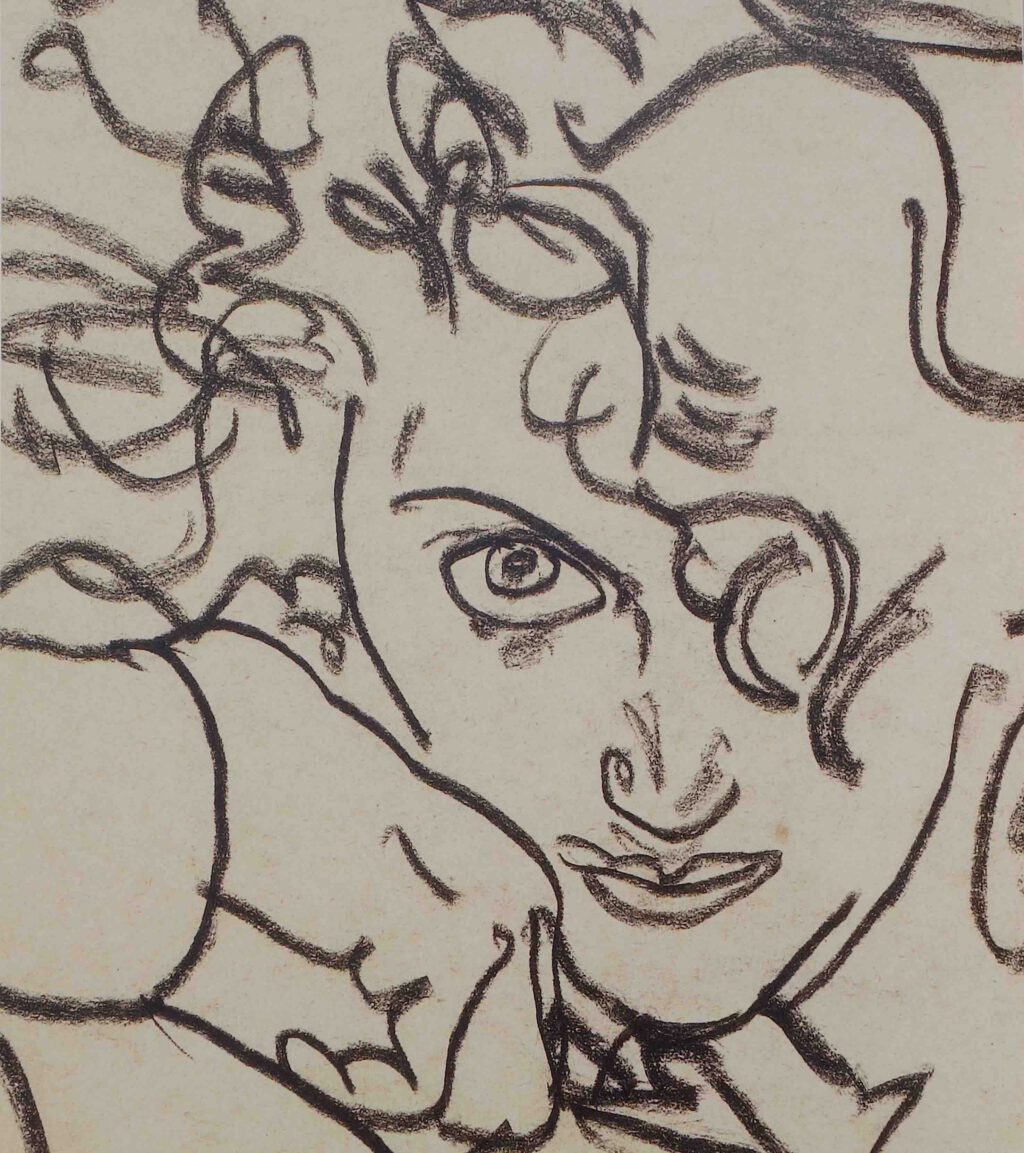

Ich liebe Gegensätze

Estimate: USD 1,500,000 – USD 2,500,000

Price realised: USD 10,990,000

Closed: 9 Nov 2023

https://www.christies.com/en/lot/egon-schiele-1890-1918-6453085

End of up-date

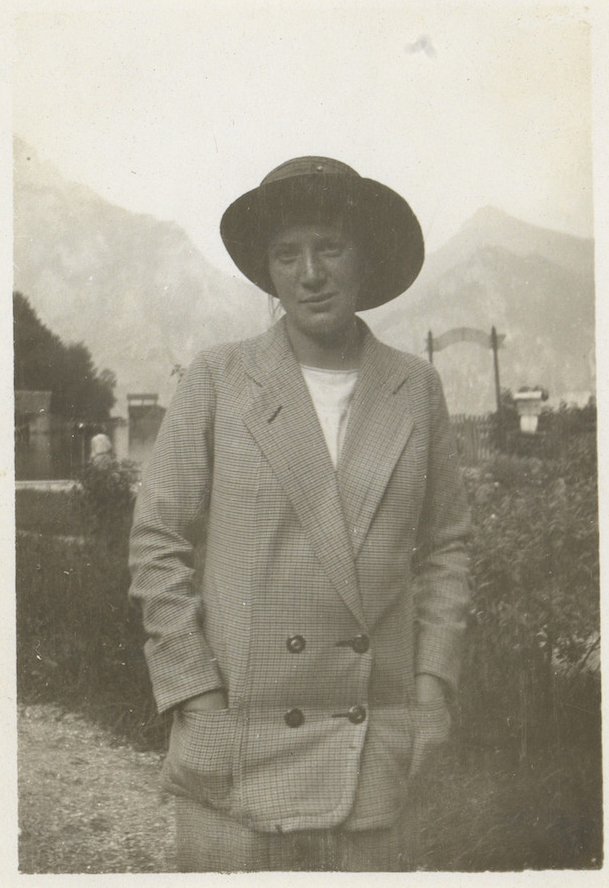

Wally Neuzil 1913

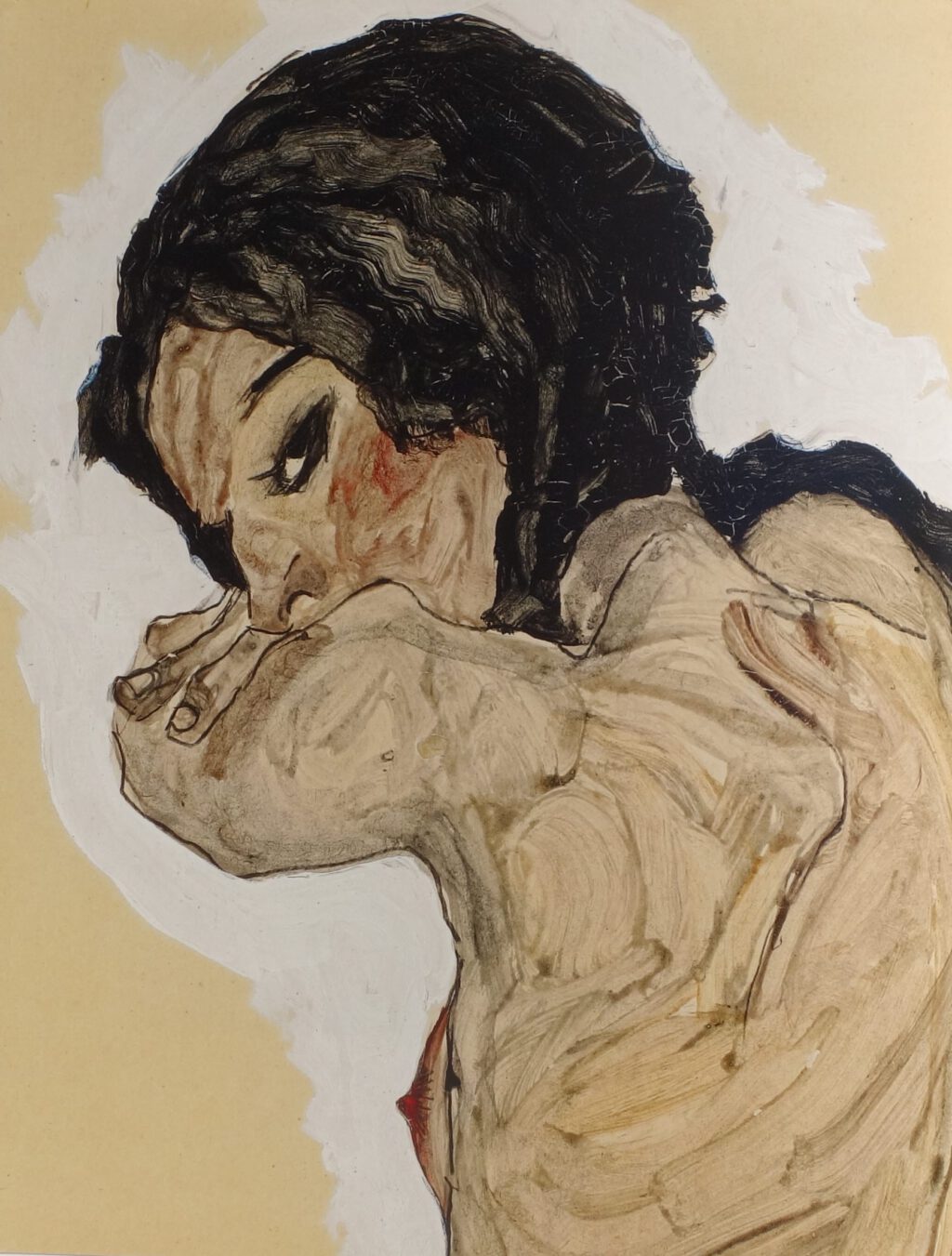

Egon Schiele “Bildnis Wally Neuzil” 1912, Öl auf Holz, 32 x 39,8 cm

Egon Schiele und Wally Neuzil 1913

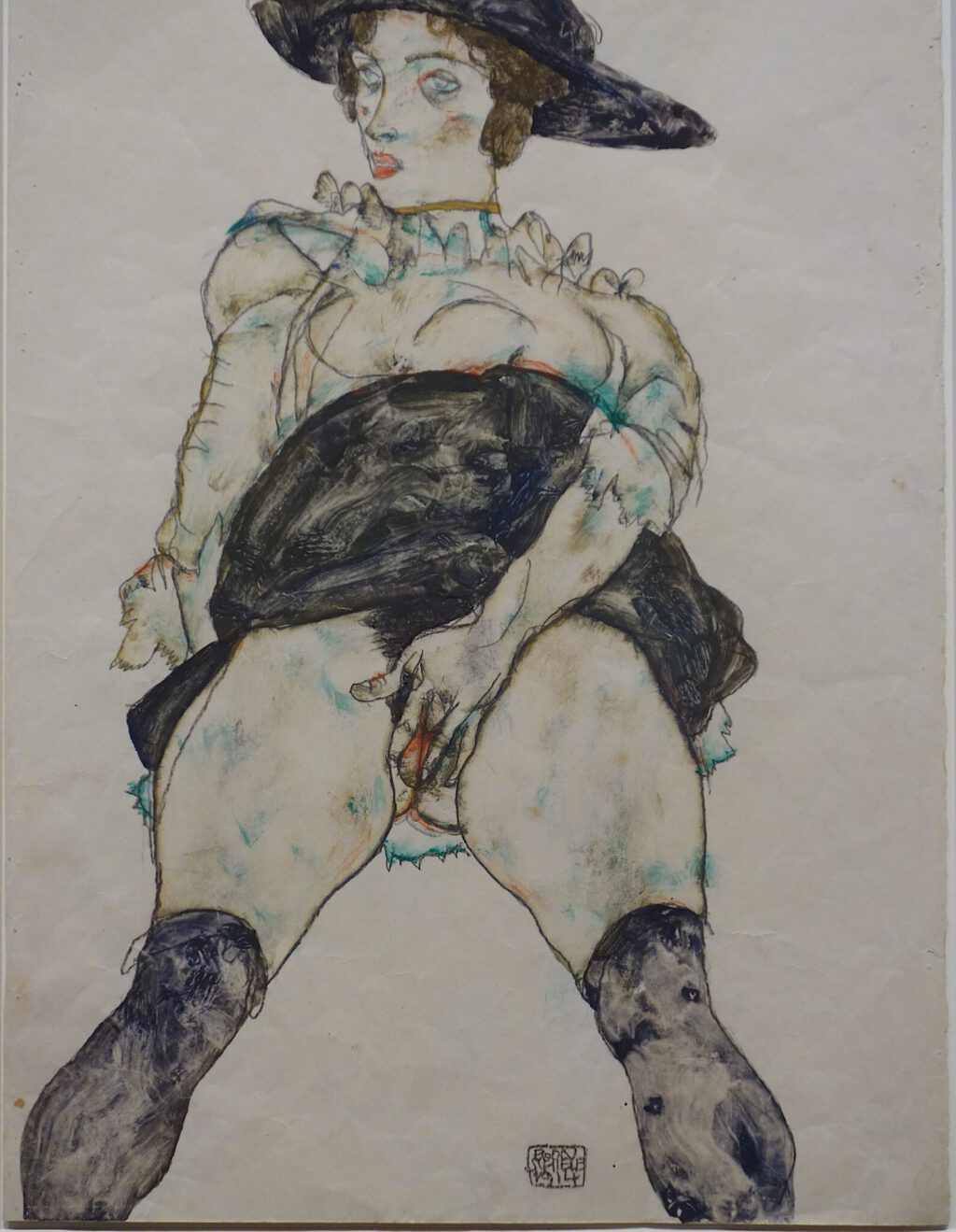

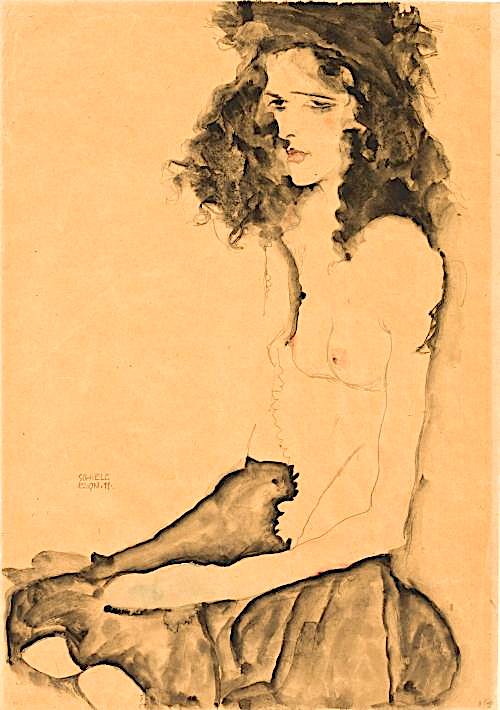

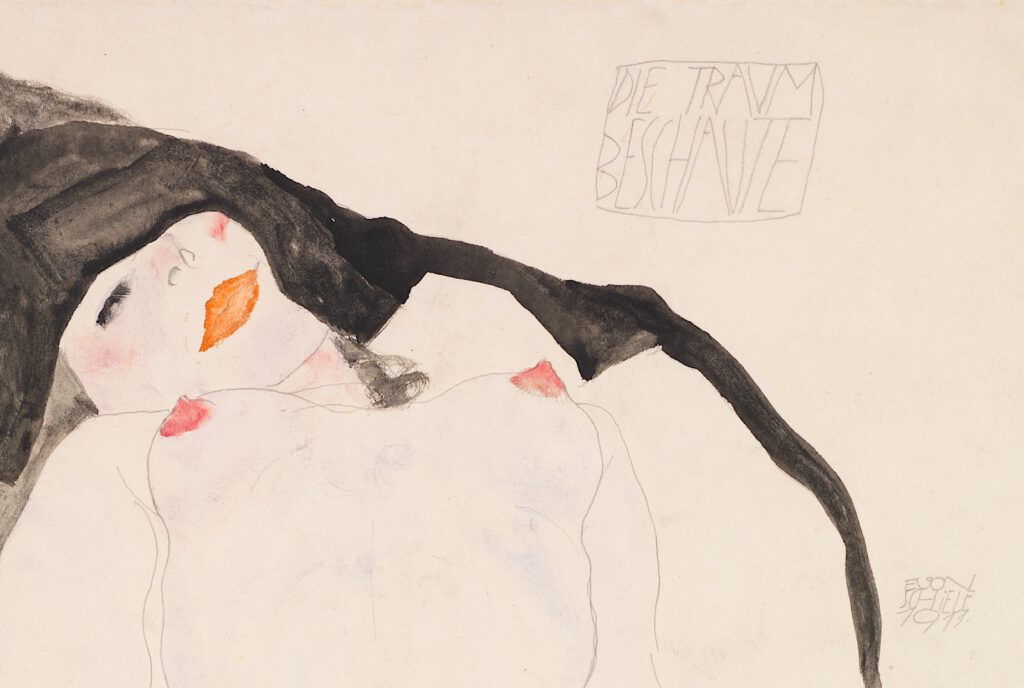

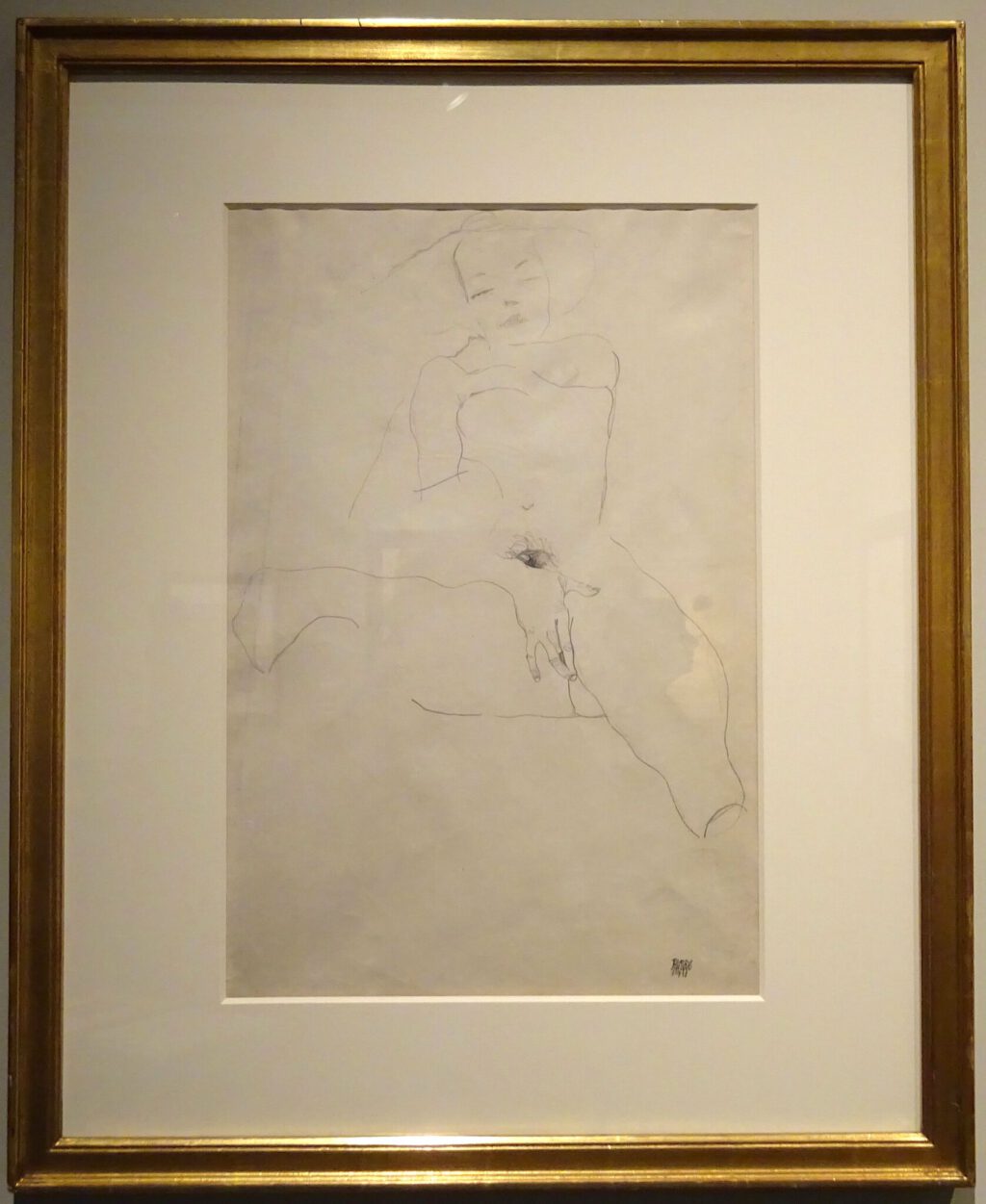

Egon Schiele “Woman with Hat Masturbating (Wally Neuzil)” 1914, Gouache and pencil on paper

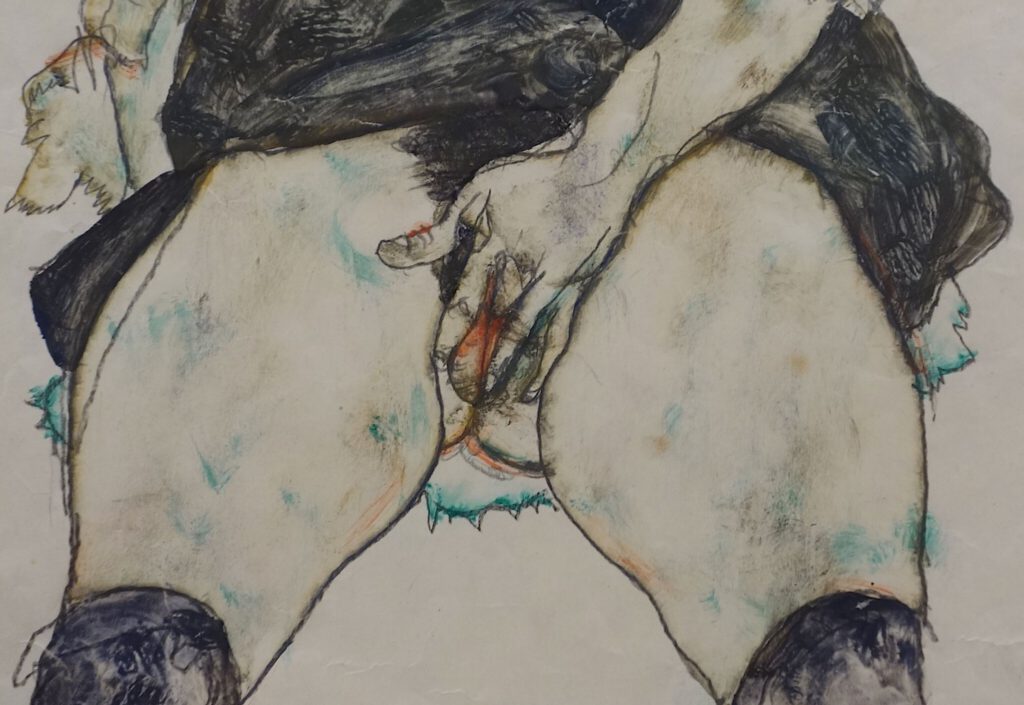

Egon Schiele “Woman with Hat Masturbating (Wally Neuzil)” 1914, Gouache and pencil on paper, detail

Egon Schiele “Woman with Hat Masturbating (Wally Neuzil)” 1914, Gouache and pencil on paper, detail

The Art Institute of Chicago

PROVENANCE

Fritz Grünbaum (1880–1941), Vienna, by 1925 [Vienna 1925]; by descent to his wife, Elizabeth (née Herzl; 1898–1942); by descent to her sister, Mathilde Lukacs, Brussels [letter from Eberhard Kornfeld, Sept. 28, 2002]; sold, Gutekunst & Klipstein, Bern, 1956, lot. 39. Galerie St. Etienne, New York, by 1957. David Kimball. Leo Askew. Sold by B. C. Holland, Chicago, to the Art Institute, 1966.

https://www.artic.edu/artworks/25342/russian-war-prisoner

up-date 2023/9/14

WARRANTS EXECUTED. In the New York Times, Tom Mashberg has the scoop that the Manhattan district attorney’s office seized Egon Schiele works that it has determined were stolen during the Holocaust from three art museums—the Art Institute of Chicago, the Carnegie Museum in Pittsburgh, and the Allen Memorial Art Museum at Oberlin College in Ohio. The pieces were once held by the Jewish art collector Fritz Grünbaum , who was forced into signing away his power of attorney while held at the Dachau concentration camp. Grünbaum’s heirs have been attempting to reclaim a number of works from his collection in civil proceedings in U.S. courts. The Allen did not comment, the Carnegie said it would “cooperate fully with inquiries from the relevant authorities,” and the Art Institute said, “We are confident in our legal acquisition and lawful possession of this work,” noting that it was “defending our legal ownership” in civil litigation.

…..

From the website “Collection Grünbaum – Art stolen from Fritz Grünbaum”

quotes:

Provenance:

As per Catalog: „Egon Schiele“ Würthle Gallery, Vienna 1925: Sammlung Fritz Grünbaum

As per Jane Kallier: Egon Schiele, The Complete Works 1998, New York: Gutekunst & Klipstein, Bern; Galerie St. Etienne, New York; David Kimball; Leo Askew; B. C. Holland Gallery, Chicago; Eugene Solow

As per Sophie Lillie. A Legacy Forlorn. The Fate of Egon Schiele ́s Early Collectors, in: Egon Schiele: The Ronald S. Lauder and Serge Sabarsky Foundation, New York 2005, S. 122 f:

…Grünbaum can be confirmed as the Owner …

As per Correspondence Kornfeld/Bratschi (handed over by Thomas Buomberger Delivery to Bern by M. Lukacs, April 24th 1956 for purchase (May 22nd, 1956): BookkeepingNr. 36765

As per Ownership History by The Art institute of Chicago:

Fritz Grünbaum (1880‐1941), Vienna, by 1925 [according to Lillie in Arnbom and Wagner‐Trenkwitz 2005, p. 151]; by descent to his wife, Elizabeth (née Herzl; 1898–1942); by descent to her sister, Mathilde Lukacs, Brussels [all early provenance is according to a letter from Eberhard Kornfeld, Sept. 28, 2002]; sold, Gutekunst & Klipstein, Bern, 1956, lot. 39. Sold, Galerie St. Etienne, New York, 1957, no. 25. David Kimball. Leo Askew. Sold by B. C. Holland, Chicago, to the Art Institute, 1966.

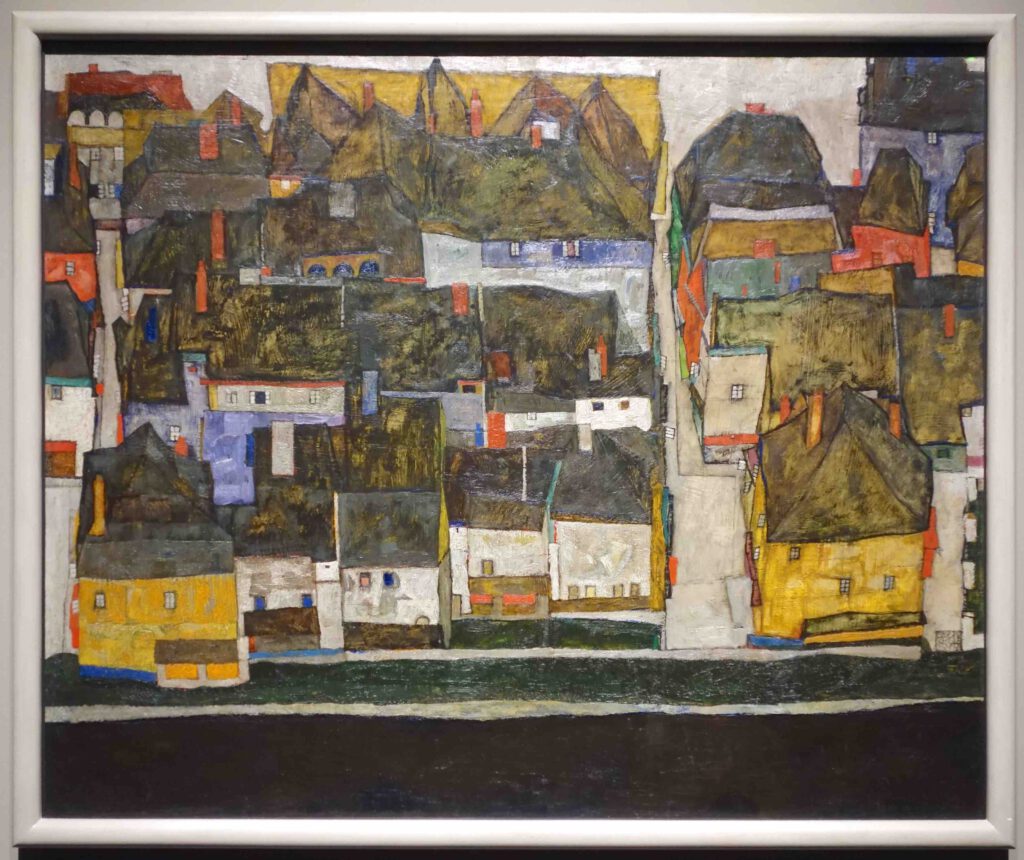

The law firm of Dunnington Bartholow & Miller LLP is leading efforts to recover Fritz Grunbaum’s stolen art collection on behalf of his heirs. On August 4, 2016, Justice Charles Ramos (Supreme Court, New York County) in a case captioned Reif v. Nagy permitted the heirs’ claims to proceed against London art dealer Richard Nagy and denied the application of the art title insurance company ARIS to intervene in the action. This case is currently proceeding. In 2014, as commemorated in a ceremony featuring former District Attorney Robert Morgenthau at the Museum of Jewish Heritage – A Living Memorial To The Holocaust, Dunnington negotiated the restitution and auction of Schiele’s Town on the Blue River at Christie’s auction house in a very successful sale. The high auction price shows that it pays to do the right thing. The heirs would appreciate any information about the artworks stolen from Fritz Grunbaum while he was in the Dachau Concentration Camp and would appreciate any persons of good faith voluntarily stepping forward to return these

artworks. The heirs call on art historians and experts in the museum community to have the courage to release scholarly reports on the stolen items in museum collections and to call on the governments of Austria and the United States to work towards taking these stolen artworks out of museum collections.

https://www.collectiongruenbaum.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/JK-1839.pdf

New York Times, Sept. 13, 2023

Schiele Works Believed to Be Stolen Are Seized From U.S. Museums

Manhattan prosecutors contend that the art in question belongs to the heirs of a collector who was a Holocaust victim.

New York investigators on Wednesday seized three artworks from three out-of-state museums that they said had been stolen from a Jewish art collector killed during the Holocaust and rightly belonged to the Nazi victim’s heirs.

The Manhattan district attorney’s office issued warrants to the Art Institute of Chicago, the Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh, and the Allen Memorial Art Museum at Oberlin College in Ohio, for works by the 1900s Austrian Expressionist Egon Schiele. According to the warrants, “there is reasonable cause to believe” that the works constitute stolen property.

A correction was made on Sept. 13, 2023

Earlier versions of this article and its headline incorrectly described the status of legal proceedings involving three out-of-state museums. The Manhattan district attorney’s office seized works by Egon Schiele under a warrant stating that the art was believed to be stolen. The prosecutors did not file criminal charges against the institutions.

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/09/13/arts/design/nazi-stolen-schiele-works-seized.html

quotes from artnet 2023/9/14:

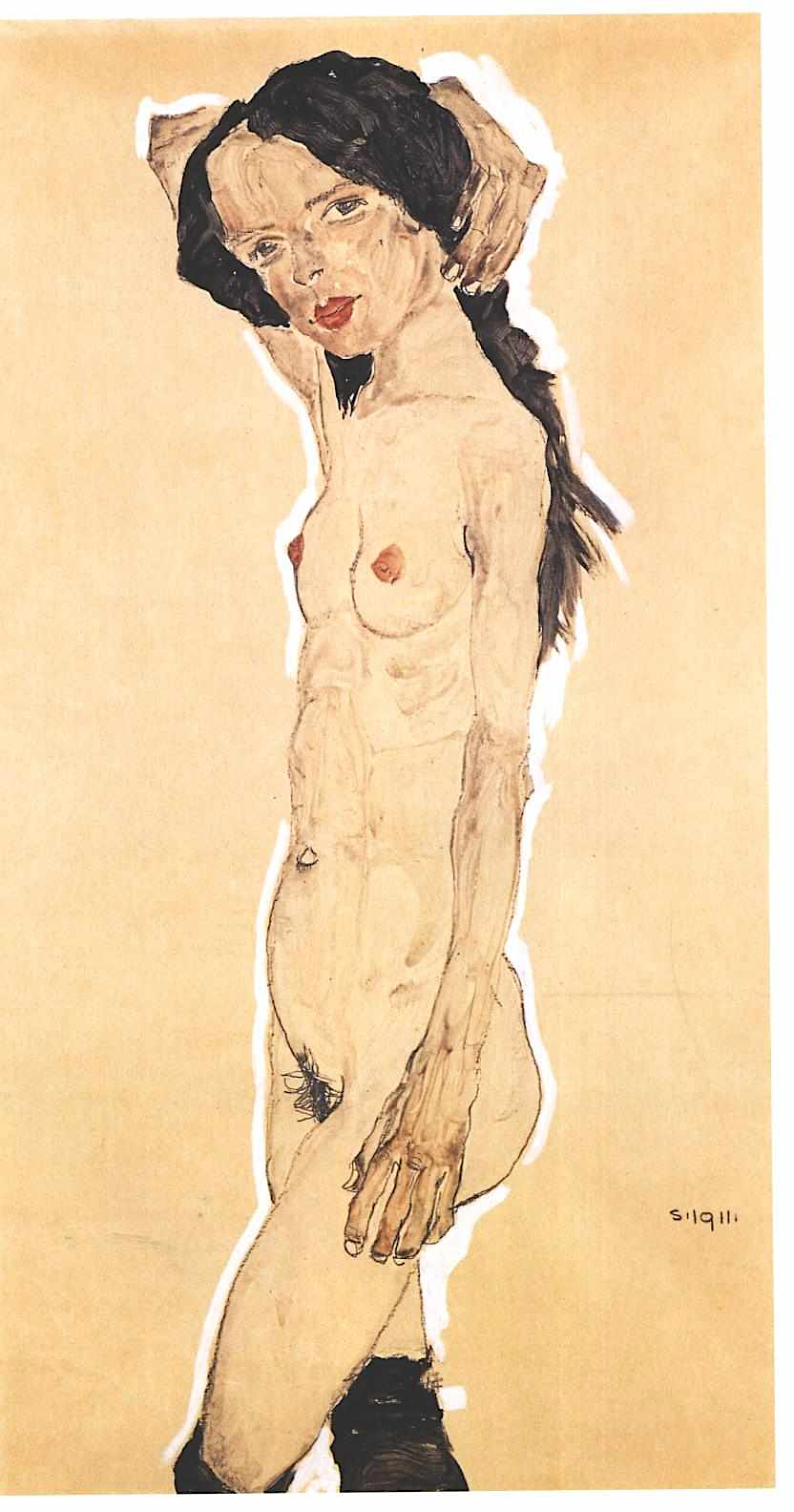

Bragg’s team, the New York Times reports, issued warrants to three out-of-state museums that owned the works: the Art Institute of Chicago, for Schiele’s Russian War Prisoner (1916); the Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh, for Portrait of a Man (1917); and the Allen Memorial Art Museum at Oberlin College, for Girl With Black Hair (1911). The warrants, which Artnet News reviewed, allow for the institutions to hold onto the artworks for now.

Valued between $1 million and $1.5 million each, the two watercolors and a pencil drawing are among roughly a dozen Schiele artworks that Grünbaum’s heirs are attempting to recover through a series of ongoing civil lawsuits. Plaintiffs in the cases are David Fraenkel and Timothy Reif, both co-trustees of Grünbaum’s estate, and Milos Vavra.

The descendants, who say that the Nazis forced Grünbaum into signing an unlawful power of attorney in 1938, while he was detained at Germany’s Dachau concentration camp, previously recovered two Schiele watercolors—Woman in a Black Pinafore (1911) and Woman Hiding Her Face (1912)—from London-based art dealer Richard Nagy. (The artworks were sold in November at Christie’s for $500,000 and $2.5 million, respectively.)

full text:

https://news.artnet.com/art-world/manhattan-da-seizes-schiele-works-2362637

From the website “Collection Grünbaum – Art stolen from Fritz Grünbaum”

quotes:

During his lifetime, Fritz Grünbaum was a well-known art collector, especially of Austrian modernist art, whose artworks were featured in famous catalogues and exhibitions. His collection extended to over 400 pieces, 80 of them have been works made by Egon Schiele (1890-1918).

This collection disappeared during NAZI time and 25% of the collection appeared on the art market in the early 1950, through Swiss Art dealer Eberhard Kornfeld.

https://www.collectiongruenbaum.com

up-date 2023/11/8

Were these artworks looted? After seizures and lawsuits, some still debate

quotes:

Instead, many embraced an alternative account told by a Swiss gallerist. He said that in 1956, 15 years after Grünbaum’s death in the Dachau concentration camp, he had come into possession of dozens of Grünbaum’s Schieles.

The gallerist, Eberhard Kornfeld, said Grünbaum’s sister-in-law had approached him, looking to sell a bunch of the Schiele artworks. Kornfeld said he bought most of the 81 Grünbaum Schieles from her and put 65 of them up for sale, an event that eventually led to more sales and resales and caused the Grünbaum Schieles to end up in collections around the world.

…

William Charron, the lawyer who represents the Leopold Museum, declined to be interviewed. But in its court filings, the museum has argued that the plaintiffs are too late in making their claim and that the federal court in Manhattan where the heirs filed their lawsuits does not have jurisdiction.

…

Kornfeld, however, has said that, instead of being diffused in multiple sales, that most of the Grünbaum Schieles were maintained as a collection, one ultimately held by Grünbaum’s sister-in-law who was herself persecuted by the Nazis and fled Vienna for Brussels in 1941. By Kornfeld’s account, the Schiele works escaped with her.

At Kornfeld’s sale in 1956, Otto Kallir, a Viennese Jewish art dealer who had helped Grünbaum buy some of the Schieles decades before, bought 18 of them, including “Dead City III.” Kallir, who fled Vienna, opened a gallery on West 57th Street in New York, Galerie St. Etienne, and later swapped “Dead City III” and three other Schiele artworks with Rudolf Leopold, a Viennese ophthalmologist who had one of the world’s best Schiele collections. Kallir received six Schiele watercolors and two drawings, plus a Gustav Klimt portrait in the exchange. Leopold later sold his vast art collection to the Austrian government, which built the Leopold Museum in Vienna.

…

The Grünbaum heirs face an uphill legal battle in the case against Austria because of the difficulties of suing a sovereign nation in U.S. courts. Typically, the courts have not allowed lawsuits against sovereign nations except in instances where there has been a viable claim that international law was violated or where nations had waived their sovereign immunity.

The Grünbaum heirs have asserted that there has been such a waiver, but Austria and its museums deny that. The case involving Austria is on a delayed schedule because of the intricacies of lawsuits involving sovereign nations, but the Art Institute case has moved forward in recent weeks as the parties debate whether the district attorney’s office, because of its seizure order, should now be a party to the suit.

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

https://artdaily.cc/news/163839/Were-these-artworks-looted–After-seizures-and-lawsuits–some-still-debate

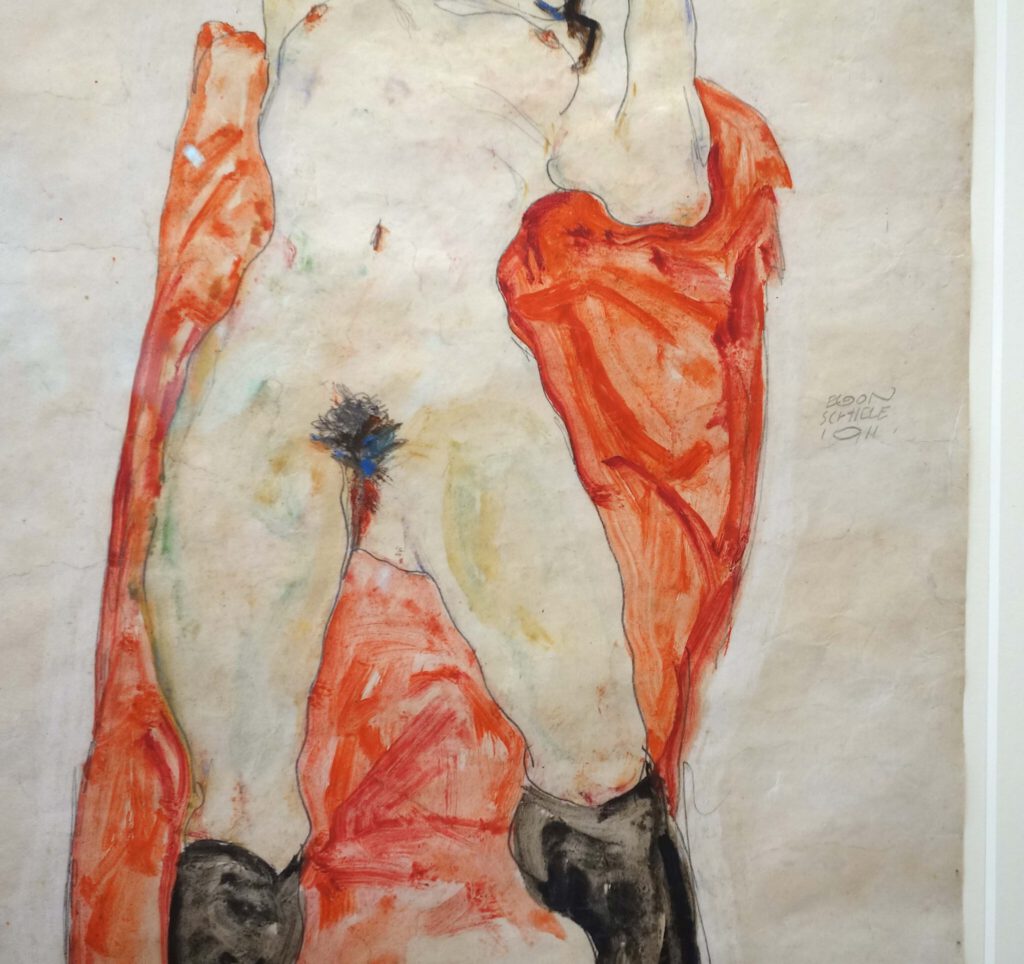

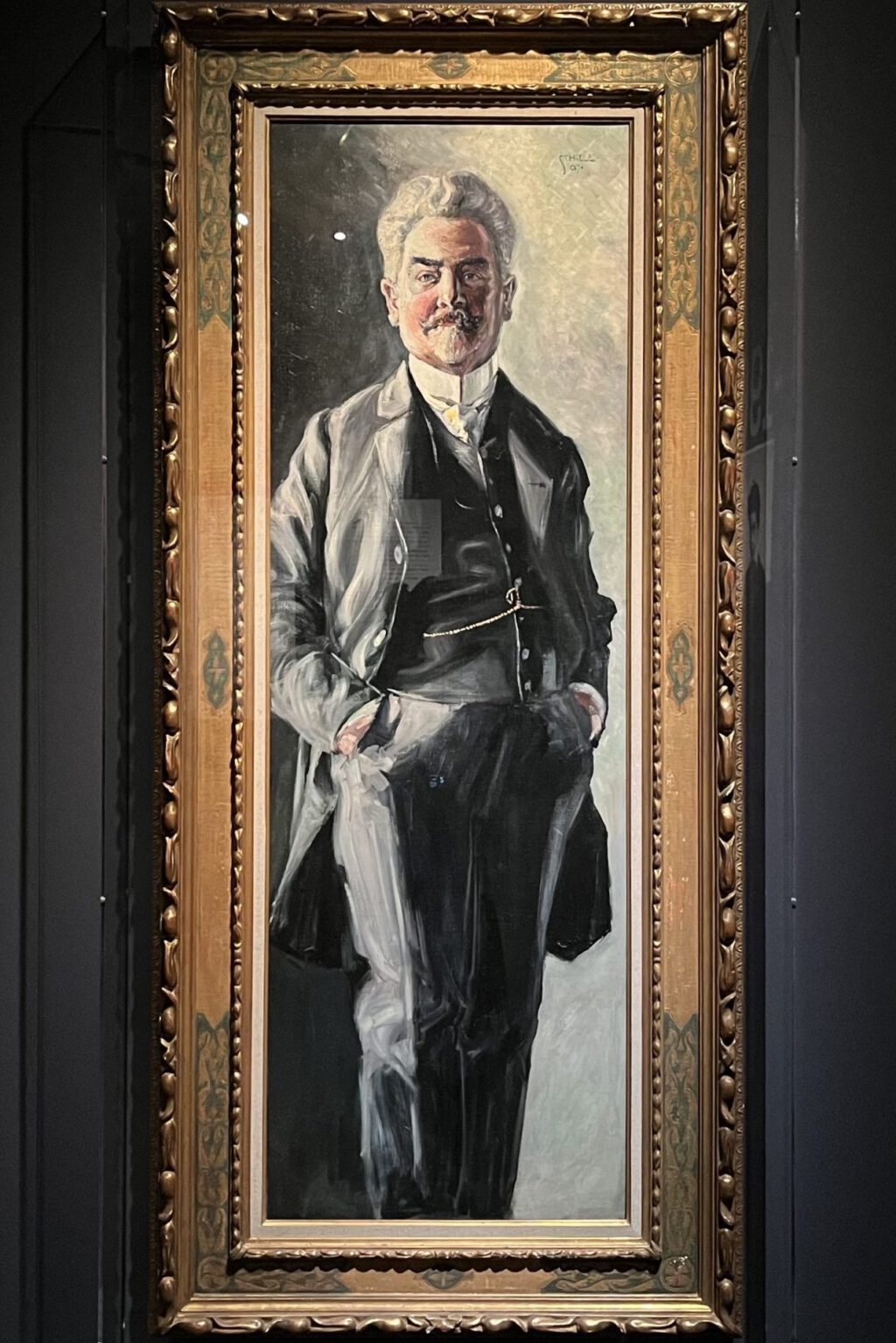

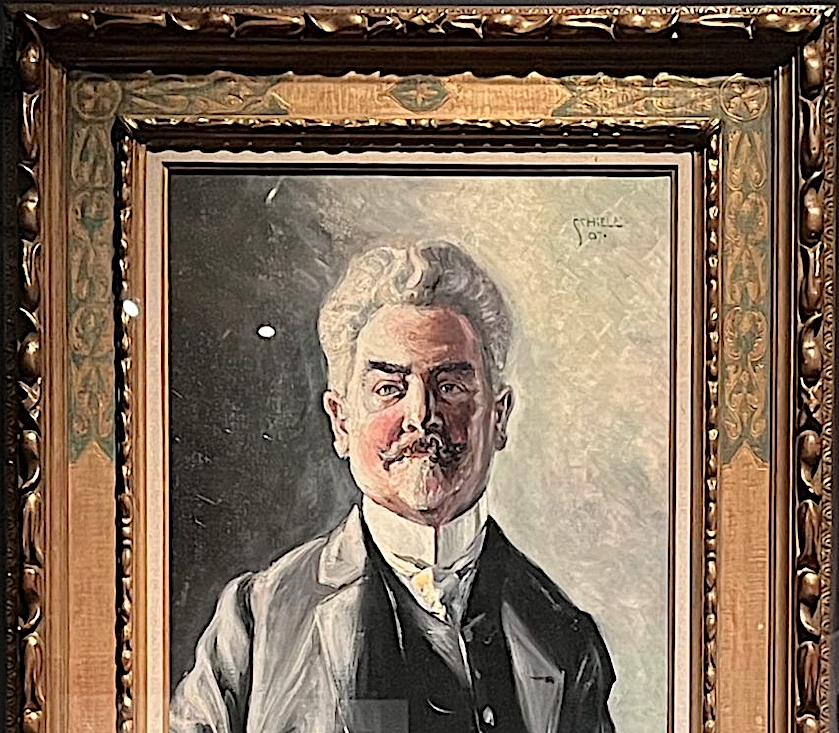

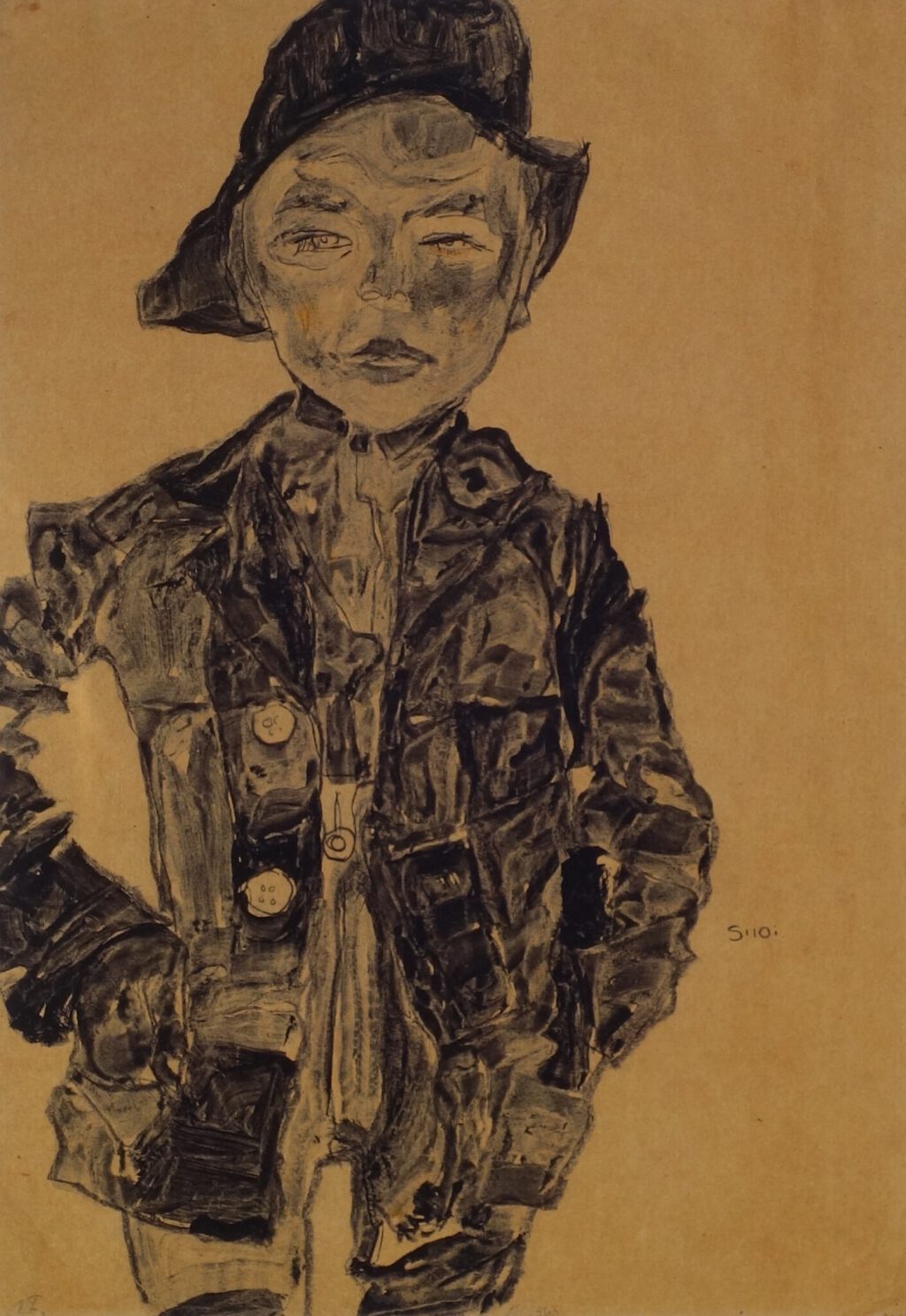

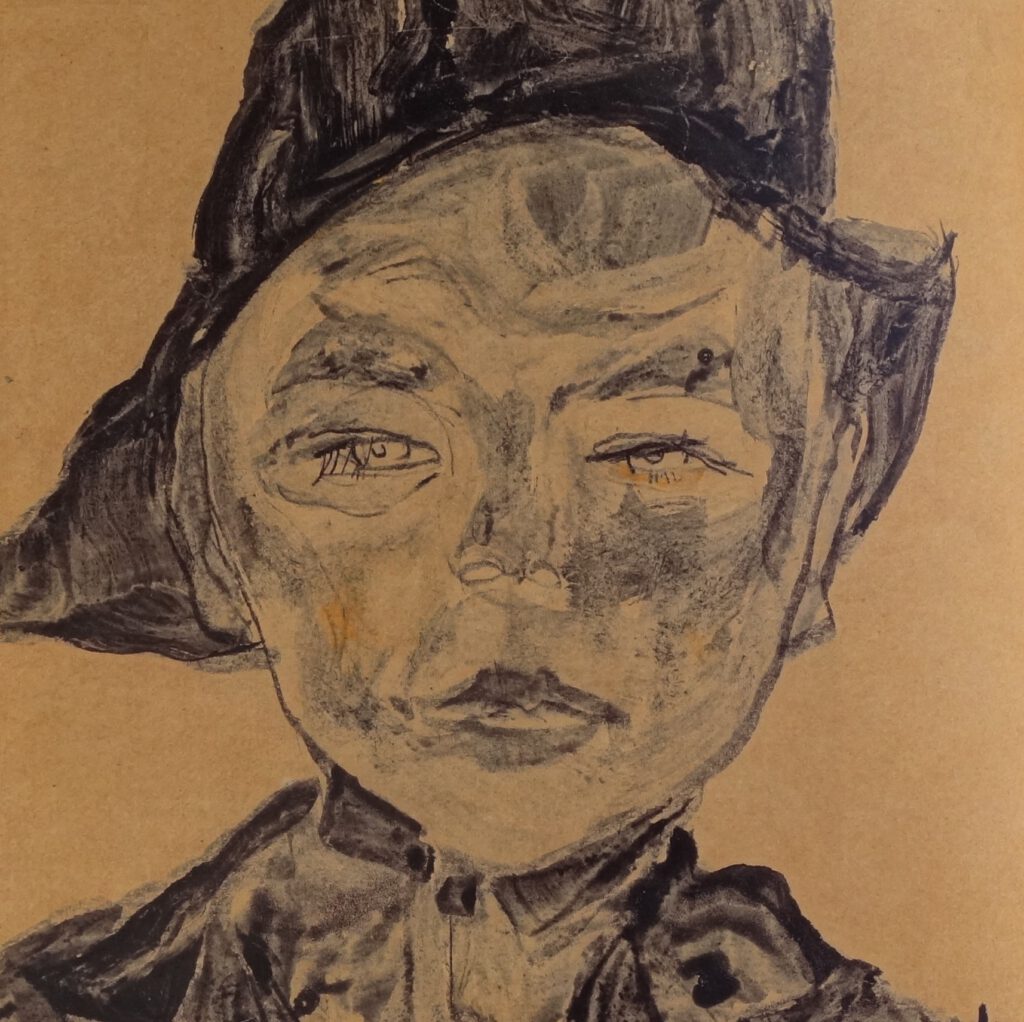

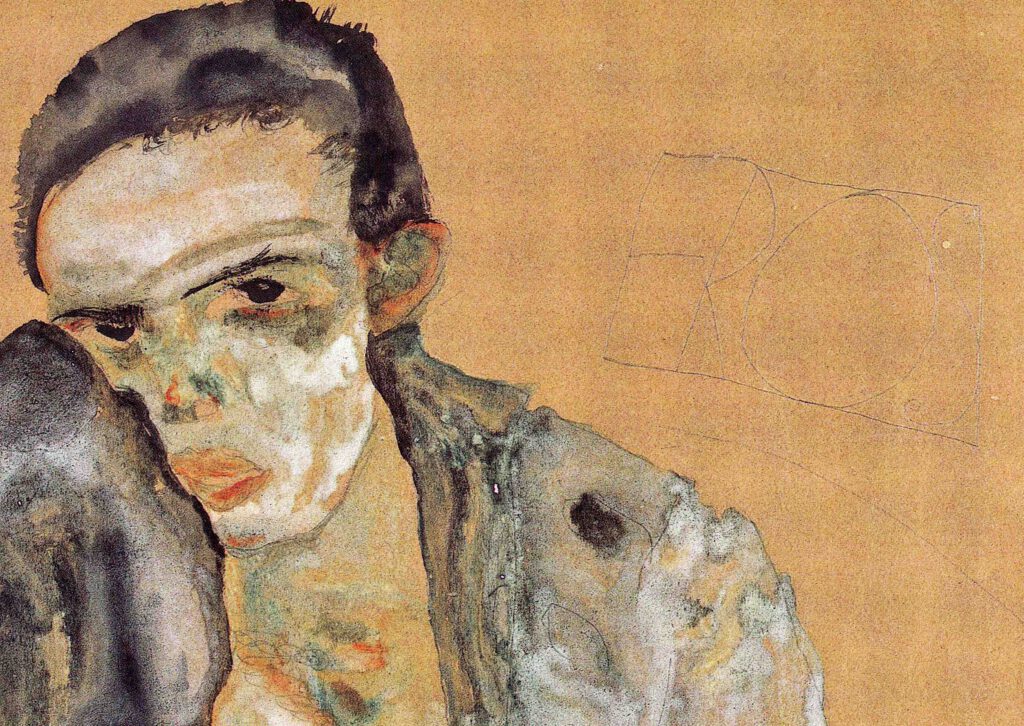

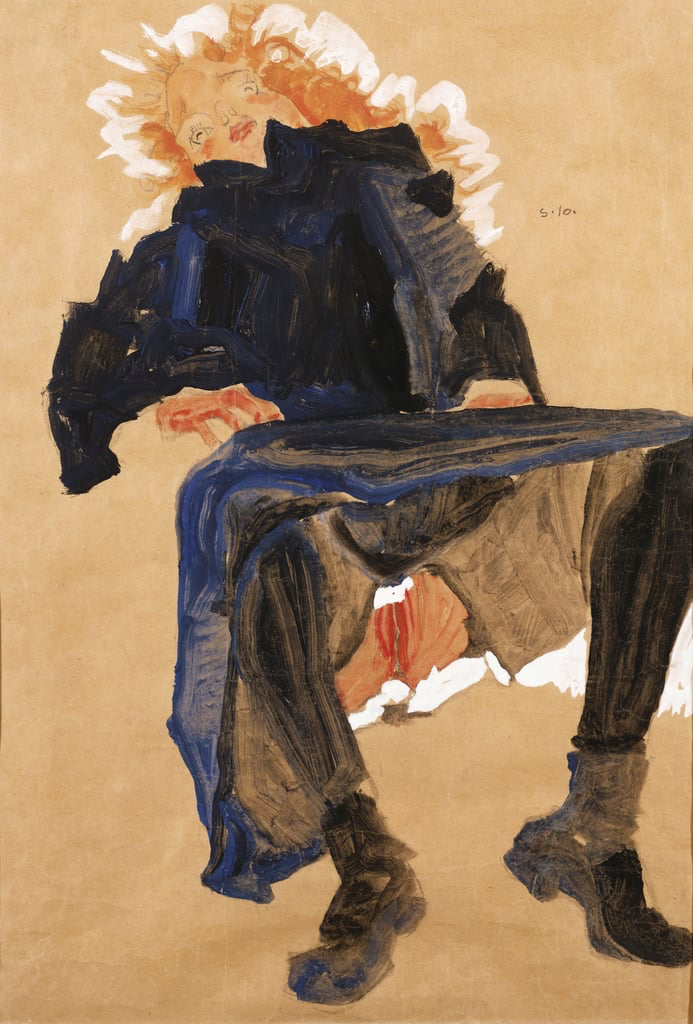

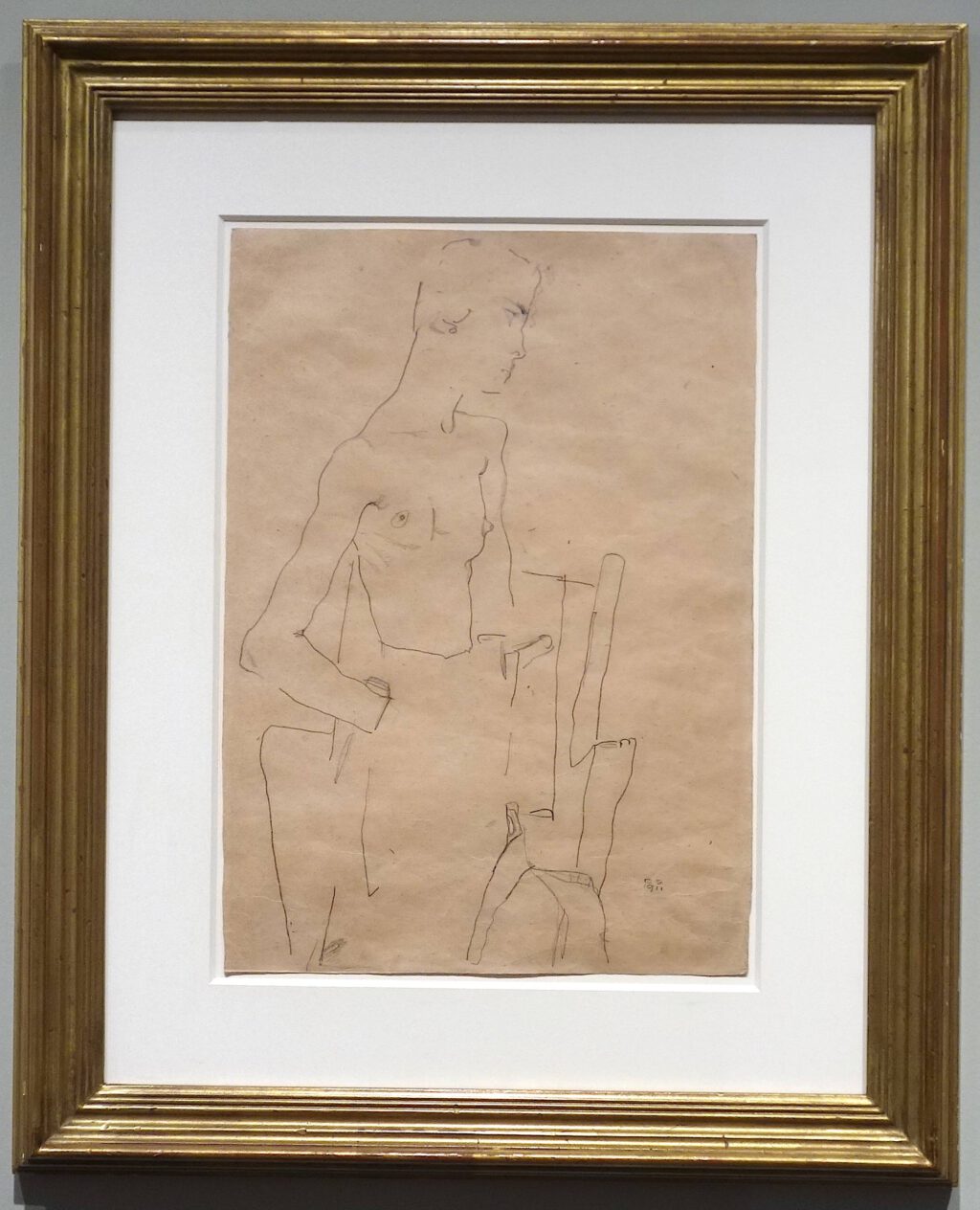

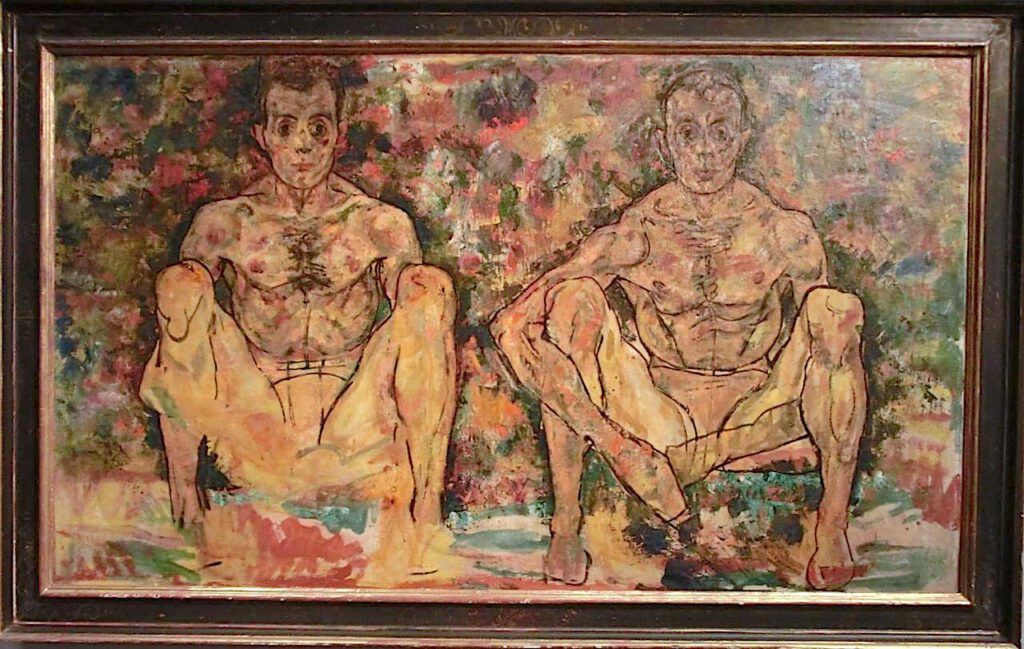

Egon Schiele – Reinerbub (Bildnis Herbert Reiner) (1910)

Above photograph taken in 2018 by me. Later, in 2022 sold @ Christie’s for 403.200 US$.

LIVE AUCTION 20989, IMPRESSIONIST & MODERN WORKS ON PAPER SALE, LOT 626

PROPERTY OF A PRIVATE CALIFORNIA COLLECTOR

EGON SCHIELE (1890-1918)

Bildnis eines Herren (Carl Reininghaus)

gouache, watercolor and black Conté crayon on paper

17 3/8 x 12 1/4 in. (44.2 x 31.1 cm.)

Executed in 1910

Price realised

USD 403,200

Estimate

USD 300,000 – USD 500,000

Closed:

19 Nov 2022

https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-6397292

In case of censorship:

Link_https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Wq-ZE457g8Q

Egon Schiele (österr. Maler)

“Egon Schiele”

Doku Österr. 2018 von Herbert Eisenschenk.

Aufnahme: ARTE 21.10.2018.

Einsamkeit, Neugierde am Okkulten, Ablehnung, Verehrung. Lust und Laster, Verdammung, Bestrafung. Nicht zu vergessen der kurze und kometenhafte Aufstieg in die strahlenden Höhen des Künstlerolymps, der sinnlos erscheinende frühe Tod, schließlich die Gegenwart mit Verehrungs- und Heiligsprechungstendenzen. Dies sind die Bausteine des kurzen Lebens von Egon Schiele. Sie und seine bis heute schwer zu entschlüsselnde Kunst bilden bis heute, 100 Jahre nach seinem Tod, jenes Material, aus dem die Legenden der Unerreichbaren gefertigt sind. Aber wer sich die Mühe macht, sich nicht von dieser affektbeladenen Fassade einschüchtern zu lassen, sondern hinter diese zu blicken, dem sollte es auch gelingen, in seiner Kunst die Seele des Menschen Schiele zu erkennen. Diese Begegnung mag verstören: Das, was sie uns mitzuteilen hat, wurde oft mit brutaler Ehrlichkeit auf Leinwände und Papier gebannt. Es ist weit entfernt von Schönheit und Harmlosigkeit angesiedelt.

Egon Schiele entkleidet die Gesellschaft und sich selbst nachhaltig und im doppelten Sinne. Wie Sigmund Freud drang auch er in jene Zonen des Menschseins vor, wo ästhetisches Empfinden eine untergeordnete Rolle spielt. Sein Blick legte die aus dem Verborgenen heraus wirkenden menschlichen Triebe genauso schonungslos frei, wie er menschliches Sein als Leidensweg des physischen und seelischen Schmerzes entzifferte.

100 Jahre nach Schieles Tod versucht die Dokumentation nicht das Genie zu huldigen, sondern die inneren Zusammenhänge aufzudecken, die Schieles unvergleichliches Werk erst ermöglichten.

Die Nackte Wahrheit – Wiener Skandale um 1900 – Egon Schiele

Junge Maler rebellieren in Wien um die Jahrhundertwende gegen den akademischen Kunstbetrieb und schockieren mit ihren Bildern die konservative Gesellschaft. Sie suchen nach neuen stilistischen Ausdrucksmöglichkeiten und greifen Tabu-Themen auf, wie Sexualität, Homoerotik und Geschlechterkampf. Die Ausstellung “Die nackte Wahrheit” im Wiener Leopold Museum zeigte die Besonderheit der Wiener Avantgarte-Künstler.

09.12.2022

EXPRESSIONISMUS AM FOLKWANG : Die Wunden, die der Kunst geschlagen wurden

Hat es jemals einen Kunstraub gegeben, der von seinen Tätern mit mehr Akribie dokumentiert wurde? Es ging um sechzehntausend Kunstwerke, fein säuberlich aufgelistet in zwei unscheinbaren Typoskripten, auf denen unter anderem der Name des Künstlers, der Titel des Kunstwerks, der Ort seines Raubs sowie sein weiteres Schicksal festgehalten wurden: „V“ steht für Verkauf, „T“ für Tausch“, „X“ für Vernichtung. Allein aus dem Essener Museum Folkwang, das 1922 aus der zunächst in Hagen beheimateten Sammlung von Karl Ernst Osthaus hervorgegangen war, verzeichnet die Inventarliste der Nationalsozialisten 1273 Kunstwerken, die als „entartet“ gebrandmarkt wurden, um sie beschlagnahmen und verkaufen zu können. Wohl kein anderes Museum hatte unter dieser Art der Devisenbeschaffungsmaßnahme unter dem Deckmantel einer kulturpolitischen Säuberungsmaßnahme stärker zu leiden als das Essener Haus, das sich der Moderne und zumal dem Expressionismus verschrieben hatte.

Heckel, Kirchner, Paula Modersohn-Becker, Munch oder Kokoschka, sie alle standen in persönlichem Kontakt mit Osthaus, der sich als Sammler und Museumsgründer rasch einen Namen gemacht hatte. Bereits 1906 hatte Heckel das Folkwangmuseum in einem Brief als „moderne und für uns mustergültige Einrichtung“ bezeichnet und als Ausstellungsort für die im Jahr zuvor begründete Künstlervereinigung „Die Brücke“ ins Auge gefasst. Auf Heckels Vorschlag, der „Brücke“ als passives Mitglied beizutreten, ging Osthaus nicht ein, doch 1907 und 1910 fanden zwei Gemeinschaftsausstellungen der Brücke-Künstler in Hagen statt. Als dann Henry van de Velde, der für Osthaus als Architekt, aber auch als wichtiger Berater aktiv war, 1912 das zehnjährige Jubiläum des Hagener Museums mit einer „Ehrengabe“ für Osthaus begehen wollte, beteiligten sich schon mehr als fünfzig Künstler bereitwillig mit eigenen Arbeiten an der Mappe, darunter Pechstein, Nolde, Schmidt-Rottluff, Kirchner, Kandinsky, Franz Marc und August Macke.

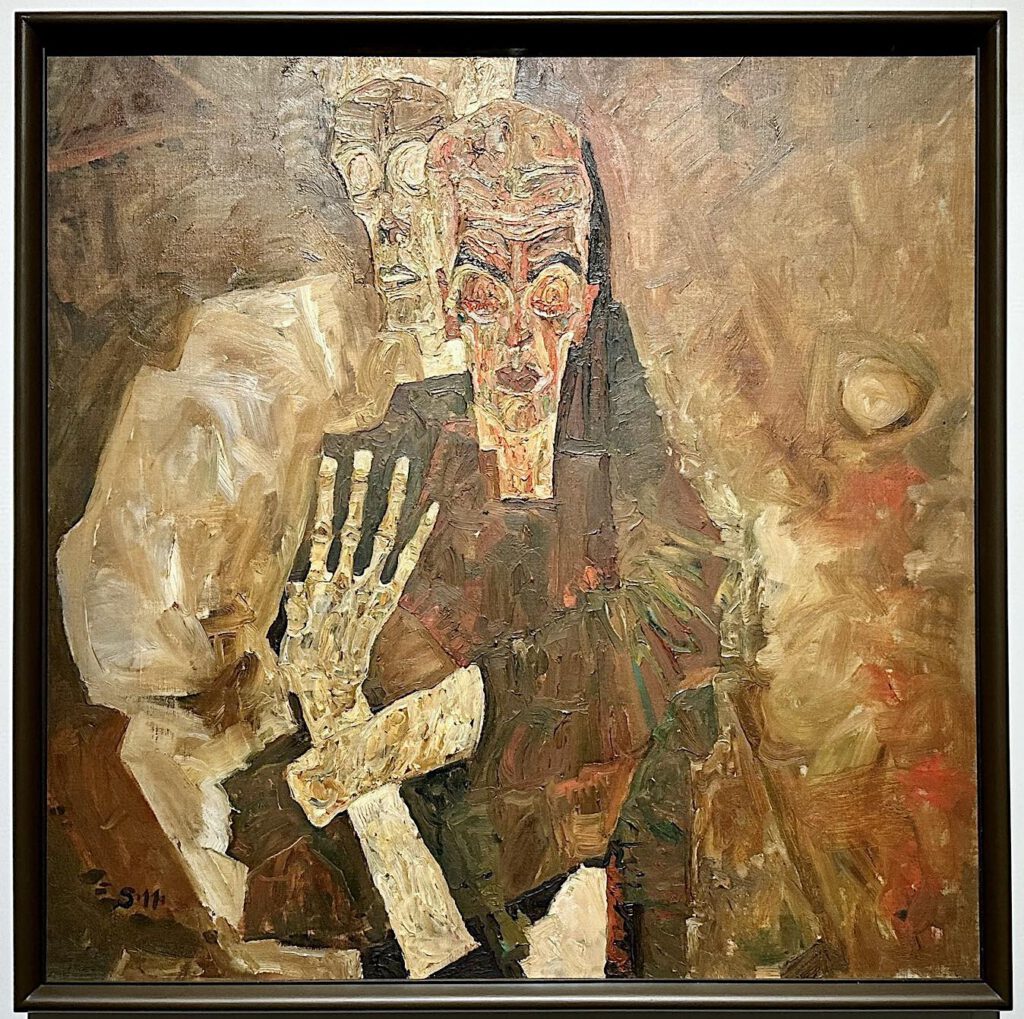

Das „beste moderne Museum“

Osthaus, der früh die französischen Vorläufer der deutschen Expressionisten für sich entdeckt hatte und sich entschieden für sie einsetzte, kaufte nicht nur mal kleinere, mal größere Arbeiten an, sondern suchte aktiv die Nähe der Künstler, indem er sie anschrieb, in ihren Ateliers besuchte, ihre Entwicklung aufmerksam verfolgte. Das Lob Egon Schieles, das Folkwang sei „das beste moderne Museum“, galt vor allem seinem Begründer.

Osthaus war kein Zauderer. Im Sommer 1910 sah er eine Ausstellung von Oskar Kokoschka bei Paul Cassirer in Berlin, im Dezember desselben Jahres war das Folkwang das erste Museum überhaupt, das ein Werk dieses Künstlers erwarb. Dabei setzte Osthaus sich nicht nur für lebende Künstler ein. Als erster deutscher Museumsdirektor kaufte er Werke van Goghs, und 1913, sechs Jahre nach ihrem Tod, ließ er eine Ausstellung mit (überwiegend verkäuflichen) Werken von Paula Modersohn-Becker ausrichten, die anschließend an vier weiteren Orten gezeigt wurde. Er selbst erwarb das berühmte „Selbstbildnis mit Kamelienzweig“, das noch heute zum Bestand des Folkwang gehört, sowie fünf Zeichnungen. Die Künstlerin selbst hatte das Folkwang zwei Jahre vor ihrem Tod besucht und berichtete darüber in einem Brief: „Das Schönste war für mich in Hagen das Museum eines Herrn Osthaus. Der hat die neuste Kunst um sich versammelt: Rodin, Minne, Maillol, Gauguin, van Gogh, einen alten Trübner, einen alten Renoir und viel anders Schönes“.

Als die Nationalsozialisten die Macht übernahmen, war Karl Ernst Osthaus seit zwölf Jahren tot. Sein Museum in Hagen, dessen Fortbestand nicht gesichert war, wurde mit dem Essener Kunstmuseum zusammengelegt, beide Häuser zusammen bildeten das neue Museum Folkwang in Essen, für das Edmund Körner einen Erweiterungsbau entwarf, dessen Festsaal Ernst Ludwig Kirchner ausgestalten sollte. Die entsprechende Korrespondenz zwischen Kirchner und Ernst Gosebruch als Museumsdirektor erstreckte sich über sieben Jahre.

Anrührende Korrespondenz zwischen Osthaus und Schiele

Briefe, Skizzen, Fotografien und andere Dokumente aus dem eigenen Archiv geben Aufschluss über zum Teil heikle Verhandlungen und Erwerbungsgeschichten, aber auch über gescheiterte Vorhaben und Projekte, etwa Kirchners nie ausgeführte Gestaltung und Ausmalung des Festsaals, dessen zentrales Motiv des „Farbentanzes“ er in drei Gemälden ausführte, die in der Ausstellung gezeigt werden. Besonders anrührend: die Korrespondenz zwischen Osthaus und dem jungen, stets in Geldnöten steckenden Egon Schiele, der seine Werke allerdings nicht verkaufen wollte: „Von Kaufen will ich nichts hören, von Bilder kaufen, das klingt ziemlich roh. – Wir tauschen! – Sie haben doch das nötige Geld und ich gebe Ihnen Bilder, wir tauschen. Kein Preis, nichts. Verstehen Sie mich?“

„Entdeckt – Verfemt – Gefeiert“, so der Titel der gut durchdachten Ausstellung zum Jubiläumsjahr, zeigt etwa 250 zum Teil großartige Kunstwerke, von Munch bis Münter, von Lehmbruck und Barlach bis Schiele. Aber im Zentrum steht das wechselvolle Schicksal des Expressionismus als einer Strömung, mit der das Museum auf eine geradezu existenzielle Weise verknüpft war. Bereits im Sommer 1933 wurde Ernst Gosebruch, der als vormaliger Direktor des Essener Kunstmuseums den von Osthaus eingeschlagenen Weg weiter verfolgt hatte, aus dem Amt gedrängt und durch Klaus von Baudissin ersetzt, der die Nationalsozialisten bei der Beschlagnahmeaktion von 1937 tatkräftig unterstützen sollte.

In einem der Nebenräume der Ausstellung sind Auszüge aus der Liste der beschlagnahmten Kunstwerke zu sehen, eine ganze Wand füllend, ins Gigantische vergrößert. Der Effekt ist erstaunlich: Das Dokument selbst ist völlig unscheinbar, aber die Vergrößerung führt die unheimliche Macht einer Bürokratie vor Augen, die Urteile nicht fällt, sondern vollstreckt und nicht selten in Form von Listen kodifiziert, um sich des Vollzugs zu rühmen.

Beschämend sind die Preise, die damals erzielt wurden. Oft liegen sie unter einer Reichsmark, betragen nur wenige amerikanische Cent oder Schweizer Rappen. Der internationale Kunstmarkt nahm regen Anteil, einige wenige Zwischenhändler wie Hildebrand Gurlitt wickelten die Geschäfte ab. Die Sammlung expressionistischer Kunst, die Karl Ernst Osthaus aufgebaut hatte, wurde in alle Winde zerstreut. Aber schon 1948 wurde im Folkwang wieder eine kleine Ausstellung mit Werken der Expressionisten gezeigt, 1958 wurde der Neubau des Museums mit einer Ausstellung zur „Brücke“ eröffnet, und noch in den Vierzigerjahren hatte man begonnen, die verlorenen Kunstwerke nach Möglichkeit noch einmal zu erwerben. Oft war das unmöglich, aber Werke wie „Kirchners Kaffeetisch“ oder August Mackes immer wieder hinreißende „Frau mit Sonnenschirm vor Hutladen“ konnten nach Essen zurückkehren. „Entdeckt – Verfemt – Gefeiert“ ist mehr als nur eine Jubiläumsausstellung, mit der das Museum sein hundertjähriges Bestehen in Essen feiert, es ist eine bedeutende Recherche nicht nur in eigener Sache. Sie führt uns das ganze Ausmaß der Wunden, die der Kunst zwischen 1933 und 1945 geschlagen wurden, noch einmal vor Augen.

Expressionisten am Folkwang. Entdeckt – verfemt – gefeiert. Im Folkwang Museum, Essen; bis zum 8. Januar 2023. Der Katalog kostet 38 Euro.

https://www.faz.net/aktuell/feuilleton/kunst-und-architektur/entdeckt-verfemt-gefeiert-expressionismus-am-folkwang-18512389.html