Warhol’s works are protected by fair use because they are “transformative” of the original photo and “add something new to the world of art” Andy Warhol Prints

Today’s Art Newspaper’s article about Andy Warhol prints in the context of photography by other persons should be taken seriously. The whole issue on copyright regarding art and photography is becoming more and more obsolete.

Quote:

Dismissing Goldsmith’s copyright infringement claim, Judge John G. Koeltl ruled that Warhol’s works are protected by fair use because they are “transformative” of the original photo and “add something new to the world of art”, according to the court papers.

For the record, especially for my Japanese readers, I am posting the complete text.

Compare also the statement by Eikoh Hosoe regarding Mishima’s photographs.

三島由紀夫のホモエロティシズム写真作品 © 細江英公

MISHIMA Yukio’s homoerotic photoworks © Eikoh Hosoe

https://art-culture.world/articles/mishima-yukio-homoerotic-photoworks-eikoh-hosoe/

Or see also

リチャード・プリンス と著作権の問題:「元ソニック・ユースのキム・ゴードン」作 @ Blum & Poe 東京

Richard Prince and copyright issues: ‘ex Sonic Youth Kim Gordon’ @ Blum & Poe, Tokyo

https://art-culture.world/articles/richard-prince-and-copyright-issues-ex-sonic-youth-kim-gordon-blum-poe-tokyo/

Warhol’s Prince series ruled fair use by a New York judge in contested copyright case

The ruling settles a heated two-year legal battle between the artist’s foundation and photographer Lynn Goldsmith, who shot the original image in 1981

Margaret Carrigan

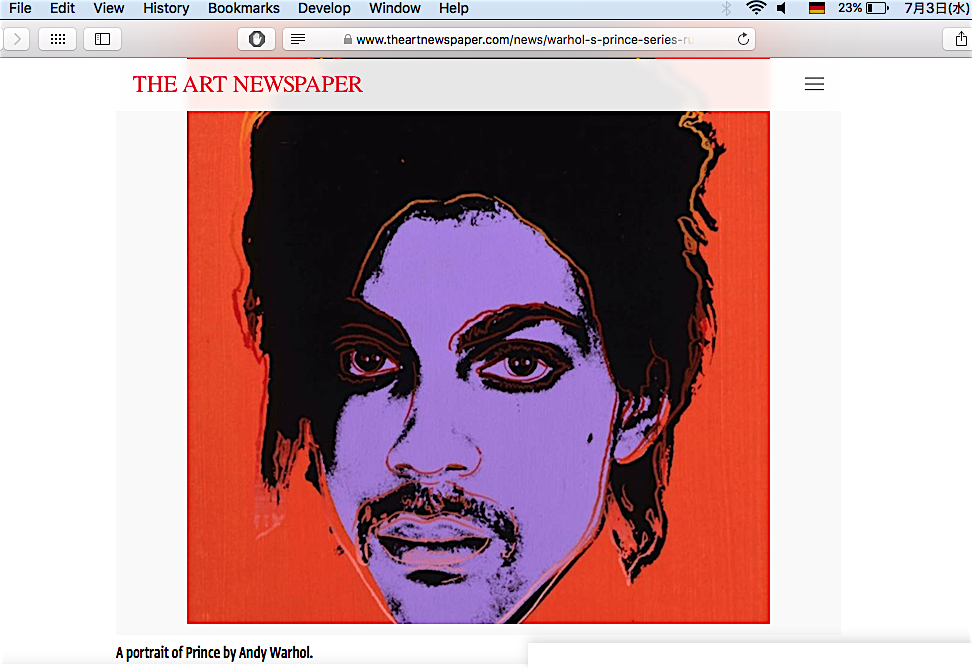

A portrait of Prince by Andy Warhol.

A New York federal judge ruled yesterday that a well-known Andy Warhol series, in which the artist modified a photograph of the pop music icon Prince, does not infringe the copyright of the photographer who took the original image.

The decision marks the end of a heated and potentially influential lawsuit brought in 2017 by the celebrity photographer Lynn Goldsmith against the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts after she claimed that Warhol violated the copyright of her photographs of Prince, taken in 1981, when they were used to make the artist’s screenprints.

Dismissing Goldsmith’s copyright infringement claim, Judge John G. Koeltl ruled that Warhol’s works are protected by fair use because they are “transformative” of the original photo and “add something new to the world of art”, according to the court papers. The 16-piece Prince Series, made by Warhol in 1984 for Vanity Fair, also does not present “market substitutes for her photograph”.

“We’re pleased that the court recognised Warhol’s invaluable contribution to the arts and upheld these works,” says Luke Nikas of the law firm Quinn Emanuel, which represents the Warhol Foundation.

Goldsmith granted Vanity Fair a one-time license to use her photograph of Prince as source material for Warhol’s illustration in 1984. In 2016, the Foundation licenced one of those portraits to Condé Nast for $10,000 for the cover of a magazine dedicated to Prince published shortly after the musician’s death. Goldsmith says she learned of Warhol’s series from online images posted after Prince died, though the portraits—a dozen of which were sold—have been exhibited in museums, including four in the Andy Warhol Museum.

When the lawsuit was filed two years ago, it immediately sparked debate about what constituted artistic appropriation versus copyright infringement. Goldsmith claimed that the Foundation violated her exclusive rights under copyright law to reproduce, display, licence and distribute works derived from her photograph. A ruling in its favour “would give a free pass to appropriation artists” and destroy licensing markets for commercial photographers, according to the initial court filings. The Warhol Foundation entreated the Manhattan federal court to “stay on the right side of history” and “reject” what it called Goldsmith’s “effort to trample on the First Amendment and stifle artistic creativity”.

In addition to declaratory judgment, the foundation is seeking retribution in the form of money, including the cost of the suit and attorneys’ fees. Monday’s ruling states that a “holistic weighing” of fair use factors “points decidedly in favour” of the foundation, which must submit proposed judgement by 8 July; Goldsmith must submit any objections by 10 July.

https://www.theartnewspaper.com/news/warhol-s-prince-series-ruled-fair-use-by-new-york-judge

up-date 2019/7/3:

Andy Warhol’s Prince Portraits Are ‘Fair Use’ of Lynn Goldsmith Photo, Federal Judge Rules

BY Annie Armstrong POSTED 07/02/19 2:03 PM

quotes:

The fight largely centered on whether Warhol had sufficiently transformed the original photograph so as to quality as fair use. Weighing aspects of the world like color and shading, the judge wrote that the Warhol “works are transformative, and therefore the import of their (limited) commercial nature is diluted.” (Goldsmith had argued that Warhol had improperly benefited from his use of the photograph.)

The opinion lays out several differences between Goldsmith’s portrait and Warhol’s iterations. “These alterations result in an aesthetic and character different from the original,” the judge wrote, adding, “The humanity Prince embodies in Goldsmith’s photograph is gone. Moreover, each ‘Prince Series’ work is immediately recognizable as a ‘Warhol’ rather than a photograph of Prince.”

Luke Nikas, a lawyer from the Warhol Foundation, told ARTnews this morning over email, “Warhol is one of the most important artists of the 20th century, and we’re pleased that the court recognized his invaluable contribution to the arts and upheld these works.”

http://www.artnews.com/2019/07/02/andy-warhol-prince-series-fair-use-lynn-goldsmith-portrait/

Judge: Andy Warhol didn’t violate Prince picture copyright

By LARRY NEUMEISTER

July 2, 2019

quote:

“The Prince Series works can reasonably be perceived to have transformed Prince from a vulnerable, uncomfortable person to an iconic, larger-than-life figure,” the judge said. “The humanity Prince embodies in Goldsmith’s photograph is gone. Moreover, each Prince series work is immediately recognizable as a ‘Warhol’ rather than as a photograph of Prince — in the same way that Warhol’s famous representations of Marilyn Monroe and Mao are recognizable as ‘Warhols,’ not as realistic photographs of those persons.”

https://apnews.com/d14de100e0454e658238546e0e036fc2

Art and Law

The Andy Warhol Foundation Has Won Out Against a Photographer Who Claimed the Pop Artist Pilfered Her Portrait of Prince

Photographer Lynn Goldsmith has vowed to appeal.

Sarah Cascone, July 2, 2019

quote:

Goldsmith claims to have spent $400,000 in legal bills to date, and expects to accrue costs in excess of $2.5 million. To help offset her legal costs, she’s taken out a loan and launched a GoFundMe campaign that has raised $17,000 to date.

https://news.artnet.com/art-world/andy-warhol-prince-copyright-case-1590703

Prince – Purple Rain (Official Video)

up-date 2021/3/27

US court sides with photographer in fight over Warhol art

A U.S. appeals court sided with a photographer Friday in a copyright dispute over how a foundation has marketed a series of Andy Warhol works of art based on one of her pictures of Prince.

The New York-based 2nd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that the artwork created by Warhol before his 1987 death was not transformative and could not overcome copyright obligations to photographer Lynn Goldsmith. It returned the case to a lower court for further proceedings.

In a statement, Goldsmith said she was grateful to the outcome in the 4-year-old fight initiated by a lawsuit from the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts. She said the foundation wanted to “use my photograph without asking my permission or paying me anything for my work.”

“I fought this suit to protect not only my own rights, but the rights of all photographers and visual artists to make a living by licensing their creative work — and also to decide when, how, and even whether to exploit their creative works or license others to do so,” Goldsmith said.

Warhol created a series of 16 artworks based on a 1981 picture of Prince that was taken by Goldsmith, a pioneering photographer known for portraits of famous musicians. The series contained 12 silkscreen paintings, two screen prints on paper and two drawings.

“Crucially, the Prince Series retains the essential elements of the Goldsmith Photograph without significantly adding to or altering those elements,” the 2nd Circuit said in a decision written by Judge Gerard E. Lynch.

A concurring opinion written by Circuit Judge Dennis Jacobs said the ruling would not affect the use of the 16 Warhol Prince series works acquired by various galleries, art dealers, and the Andy Warhol Museum because Goldsmith did not challenge those rights.

The ruling overturned a 2019 ruling by a judge who concluded that Warhol’s renderings were so different from Goldsmith’s photograph that they transcended copyrights belonging to Goldsmith, whose work has been featured on over 100 record album covers since the 1960s.

U.S. District Judge John G. Koeltl in Manhattan had concluded that Warhol transformed a picture of a vulnerable and uncomfortable Prince into an artwork that made the singer an “iconic, larger-than-life figure.”

In 1984, Vanity Fair licensed one of Goldsmith’s black-and-white studio portraits of Prince from her December 1981 shoot for $400 and commissioned Warhol to create an illustration of Prince for an article titled “Purple Fame.”

The dispute emerged after Prince’s 2016 death, when the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts licensed the use of Warhol’s Prince series for use in a magazine commemorating Prince’s life. One of Warhol’s creations was on the cover of the May 2016 magazine.

Goldsmith claimed that the publication of the Warhol artwork destroyed a high-profile licensing opportunity.

Attorney Luke Nikas said the Warhol Foundation will challenge the ruling.

“Over fifty years of established art history and popular consensus confirms that Andy Warhol is one of the most transformative artists of the 20th Century,” Nikas said in a statement. “While the Warhol Foundation strongly disagrees with the Second Circuit’s ruling, it does not change this fact, nor does it change the impact of Andy Warhol’s work on history.”

Attorney Barry Werbin, who represented Goldsmith in the lower court, called Friday’s ruling “a long overdue reeling in of what had become an overly-expansive application of copyright “transformative” fair use.”

“The decision helps vindicate the rights of photographers who risk having their works misappropriated for commercial use by famous artists under the guise of fair use,” he said.

The three-judge 2nd Circuit panel said its ruling should help clarify copyright law. It cautioned against judges making “inherently subjective” aesthetic judgments, saying they “should not assume the role of art critic and seek to ascertain the intent behind or meaning of the works at issue.”

It repeatedly compared the copyright issues to what occurs when books are made into movies. The movie, it noted, is often quite different from the book but yet retains copyright obligations.

The appeals court also said the unique nature of Warhol’s art should have no bearing on whether the artwork is sufficiently transformative to be deemed “fair use” of a copyright, a legal term that would free an artist from paying licensing fees for the raw material it was based on.

“We feel compelled to clarify that it is entirely irrelevant to this analysis that “each Prince Series work is immediately recognizable as a ‘Warhol,’” the appeals court said. “Entertaining that logic would inevitably create a celebrity-plagiarist privilege; the more established the artist and the more distinct that artist’s style, the greater leeway that artist would have to pilfer the creative labors of others.”

Another case, 2022/7/8

French Court Tosses Out Sculptor’s Lawsuit Over Authorship of Maurizio Cattelan Works

July 8, 2022

A French judge has dismissed a lawsuit over whether Maurizio Cattelan could be considered the true author of some of his most famous sculptures.

Sculptor Daniel Druet had sued Cattelan’s gallery, Perrotin, and the Monnaie de Paris, the art space that mounted a Cattelan show in 2016. Druet claimed that he was the true maker of nine of Cattelan’s works, among them Him, a famed 2001 sculpture of a kneeling Adolf Hitler.

The Paris court that issued the decision said that Druet, a maker of wax effigies, was effectively working for hire when Cattelan asked him to help produce the works and was therefore not the author of these objects.

The judgement reads, in part, “Daniel Druet was in no position – nor did he seek to do so – to take the slightest part in the choices relating to the scenic setting of the said effigies (choice of building and size of the rooms housing a given character, direction of the gaze, lighting, even the destruction of a glass roof or the parquet floor to make the staging more realistic and striking) or the content of the possible message to be conveyed through this staging.”

Druet and Emmanuel Perrotin, the founder of the Paris-based gallery that represents Cattelan, agreed that the terms of the agreement between the sculptor and Cattelan were blurry. But the two diverged on whether that should ultimately matter when it comes to determining who was the true author of these works.

According to Le Monde, Druet must pay 10,000 euros to Perrotin and the Monnaie de Paris. It wasn’t immediately clear whether he intended to appeal the decision, the French publication said.

Pierre-Yves Gautier and Pierre-Olivier Sur, two lawyers representing Perrotin, said in a statement, “beyond this court decision, it is conceptual art that is now protected by the rule of law.”

https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/maurizio-cattelan-authorship-lawsuit-dismissed-1234633671/

up-date 2023/5/19

May 18, 2023

SUPREME COURT RULES AGAINST WARHOL FOUNDATION IN LANDMARK COPYRIGHT CASE

The US Supreme Court today ruled 7-2 against the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts regarding the question of whether Warhol’s use in his own work of a photo of the musician Prince by Lynn Goldsmith constitutes fair use. The decision had been hotly anticipated in the wake of the Court’s October 12, 2022, hearing of the case, which Goldsmith originally launched six years ago in New York State.

Goldsmith alleged that the late Pop artist illegally used her 1981 photo of the Royal Purple One in his 1984 “Prince Series,” a series of sixteen screen prints featuring the rock icon’s visage. Warhol created the series while on assignment for Vanity Fair, whose parent company, Conde Nast, licensed the photo from Goldsmith for onetime use, paying her $400. A single work from the series, Purple Fame, ran in the magazine, and the photographer was credited. According to Goldsmith, Warhol did not seek her permission to use her photo for the sixteen-part series, nor did he offer her credit or recompense. She was moved to sue when, following Prince’s untimely 2016 death, Vanity Fair ran another work from the series, Orange Prince, in a commemorative issue, paying the Warhol Foundation $10,000 for the privilege, but failing to credit or compensate Goldsmith.

A New York federal district judge originally ruled in favor of Warhol on the grounds that the Pop artist’s work was sufficiently transformative and thus fell within the realm of “fair use.” Goldsmith appealed and was allowed to continue her suit. “The district judge should not assume the role of art critic and seek to ascertain the intent behind or meaning of the works at issue,” wrote Judge Gerard Lynch of the US Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. “That is so both because judges are typically unsuited to make aesthetic judgments and because such perceptions are inherently subjective.”

Writing for the majority, Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor noted that “Lynn Goldsmith’s original works, like those of other photographers, are entitled to copyright protection, even against famous artists.”

In a statement provided to Artforum, Warhol Foundation president Joe Wachs said: “We respectfully disagree with the Court’s ruling that the 2016 licensing of Orange Prince was not protected by the fair use doctrine. At the same time, we welcome the Court’s clarification that its decision is limited to that single licensing and does not question the legality of Andy Warhol’s creation of the Prince Series in 1984. Going forward, we will continue standing up for the rights of artists to create transformative works under the Copyright Act and the First Amendment.”

The case has been closely watched, as it is expected to have wide-ranging repercussions for artists whose work is themed around appropriation. The decision comes just days after a court ruled that two suits against noted appropriation artist Richard Prince could proceed. Those cases involve Prince’s unauthorized use of Instagram photos, and likewise center on issues of transformation and fair use.

Up-date 2023/6/2

Why Andy Warhol’s ‘Prince’ Is Actually Bad, and the Warhol Foundation v. Goldsmith Decision Is Actually Good

Ben Davis, June 1, 2023

Quotes:

…

Do we actually believe, when it comes to “fair use,” in a “celebrity-artist exception?”

…

Because the art world often trades in unique works that “comment” on the more pervasive popular culture, it instinctively assumes a defensively maximalist posture on appropriation (as opposed to the photography world, which has always been instinctively anti). And because Kagan’s dissent amounts to an extended defense of the value of Andy Warhol’s art, she has been seen as speaking for people who “get art.” Honestly, though, I think Kagan leaves out a major, obvious fact about this Warhol “Prince” artwork, thereby sidestepping the major creative questions at play.

And that is that it is a pretty bad Warhol. I actually think that’s important.

Is It (Good) Art?

I mean, really, look at it. For the Pop art fans out there—do you truly think this “Prince” is Warhol working at the peak of his powers? Obviously not.

Kagan begins her text with an extended description of a totally different Warhol work, his much more famous Marilyn (1964). She describes in detail the process of creative transformation that went into taking a publicity photo and making it into the famous canvas known everywhere today. Kagan cites the idea of Marilyn as “a biting critique of the cult of celebrity, and the role it plays in American life.” She talks about the critical value of Warhol’s art: “He manifested, in short, the dehumanizing culture of celebrity in America.”

And then Kagan simply says, “As with Marilyn, similarly with Prince.” The dissent will go on, over and over through its many pages, to say that Sotomayor and the other justices just don’t get the deep, critical take on the modern condition embedded in Warhol’s “Prince” series. She speaks of the “conveyance of new messages about celebrity culture and its personal and societal impacts” in his Prince canvases. She goes so far as to reference the “dazzling creativity in the Prince image.”

But, sorry, no. The Prince image is hack work. That is not an opinion of the “‘I could paint that’ school of art criticism”; it’s a common critical take on the late Warhol. The guy fell off as he got older.

The ‘60s Warhol of the the Marilyns and Jackies, the “Deaths and Disasters,” the “Thirteen Most Wanted,” Coca-Colas and Soup Cans—he’s witty and innovative here, using relatively low-fi means of silkscreen and artistic reframing, recoloring, and repetition to give a sense of distracted, channel-surfing glamour to the original images.

Late period Warhol is a different matter. There, he’s a bit adrift, living off of his previous glories to pay for his lavish lifestyle and many pet projects (e.g. Interview magazine). His “Society Portrait” era had his assistants churning out huge numbers Warhol-ized portraits at $25,000 a pop for any low-level celebrity or thirsty socialite who wanted one, as a money-making scheme. (He charged an additional $15,000 for extra panels.)

The 1984 Prince portrait was an even lower kind of hack work building on top of those mass-produced portraits, applying his by-then-signature style to a topical subject, to order. Kagan is appalled that the majority acts as if Warhol was just applying a Warhol “Instagram filter”—but that’s not too far from what he was doing in this case.

The Question of the Hack

Does it matter, though? Quality is subjective. Mediocre art has a right to exist too. And the late Warhol has its apologists. I just think that the magic of the name “Warhol” is clouding people’s perceptions of the kinds of arguments that need to be made about these particular works.

What if the name were “Mr. Brainwash” instead?

A decade ago, the much-loathed street artist lost a lawsuit for his appropriation of a famous 1977 photo of Sid Vicious, by Dennis Morris, the band’s photographer. The case was very similar. Brainwash made multiple Sid Vicious-based works he sold as part of his show “Life Is Beautiful,” doing different things to them—but at least one basically looked like the same photo, slightly recolored, but with a little paint thrown on it. The judge in that case said that “Most of the Defendants’ works add certain new elements, but the overall effect of each is not transformative” (similarly, Sotomayor cautions that the recent decision “does not mean that all of Warhol’s derivative works, nor all uses of them, give rise to the same fair use analysis.”)

In any case, Mr. Brainwash lost, but he tried to defend himself with exactly the same arguments about his work that Kagan imputes to Warhol’s “Prince”: that his color choices were meaningful and that the work was somehow “commentary on Sid Vicious’s persona and on the nature celebrity generally.” The judge noted that this appeared to be a “post-hoc rationalization,” and found unconvincing Brainwash’s defense that “no evidence about transformativeness was submitted prior to the reply because Defendants considered the transformative nature of the work self-evident.”

Essentially, the message was: If you are going to use the “fair use” defense to commercialize someone else’s copyrighted work, you have to at least pretend to try.

At that time, due to Mr. Brainwash’s rep as a high-test hack, few were sympathetic to him in the art world. (If you want to see just how low-effort appropriation art can be, go watch Mr. Brainwash’s assistants talk about his process in Exit Through the Gift Shop—it’s at about the hour mark.)

The question of eager, un-creative uses of appropriation by powerful artists who are out of ideas and would like to coast on other people’s unique works is as important to address as the question of actual creative uses of appropriation!

Stressing the “Use” in Fair Use

And there’s a good chance that Warhol Foundation v. Goldsmith would not even have affected the Brainwash case. The Court ducked the question of whether Warhol could make art out of Goldsmith’s photo (it “expresses no opinion as to the creation, display, or sale of the original Prince Series works”). It chose instead to focus on the novel-to-this-case question of licensing.

…

Interestingly, although Kagan cites art critic and philosopher Arthur Danto on the second page of her dissent as an authority on the value of Warhol, I think Danto would agree that “use” is a key category. Danto’s entire philosophical argument, which emerged from his consideration of Warhol’s Brillo Boxes, was that the contextual “world” around an image is what made its meaning. The importance of visual transformation of the kind Kagan spends her time trying to vindicate in Warhol’s case was what he was arguing against, actually.

… And We Have to Talk About A.I. and Appropriation

Look, I’m not really equipped to elucidate the finer-grained legal questions. There really are unscrupulous people looking to exploit every angle. But to turn over all my cards, I think that the reason that I am more responsive to the majority here is that the topic of the hour is generative A.I. art.

…

The subsequent decades of rapid technological transformation—prior to A.I.—already not only created an explosion of creative new forms of copying, but also eroded the potential for a stable creative career (something Astra Taylor explored in some passionate depth some time ago.) In the last 10 years, the realization has really set in that the maximalist “free culture is by definition good and progressive” position is not sustainable for most working creatives.

The new wave of generative A.I. is essentially a doomsday device crafted to demolish every form of stable protection for unique creative works. Trained on unthinkably huge amounts of often copyrighted materials, and capable of creative feats at speed, it sells the magical ability to target anything and remix it just enough so that you don’t need to worry about credit or compensation for any original labor, for whatever “use” you want.

It is very hard to regulate this technology. Still, the law is one of the only tools we might have to claw back shreds of value for original creators as every work of human creation is cheerfully dumped into the universal sausage grinder of Silicon Valley capital.

Tech companies were certainly watching Warhol Foundation v. Goldsmith in advance. According to Bloomberg, they are now pondering what effects it might have for the A.I. generators. Of course, the actual decision to my eye seems deliberately specific—and so far not even the threat of humanity’s complete extermination has been enough to slow the corporate A.I. juggernaut. So I am not that optimistic about any meaningful change of course.

But reading the Kagan/Sotomayor back-and-forth has hit home to me that it’s not going to help the creative industries in navigating this perilous terrain if they remain completely attached to an automatic romanticization of Warhol-ian appropriation. It might actually be useful to think in a nuanced way about how the Warhol of 1964 is different than the Warhol of 1984 if we are going to find a way through the world of 2024.

full text:

https://news.artnet.com/opinion/warhol-foundation-v-goldsmith-fair-use-2311801

up-date:

The Supreme Court’s Warhol Decision Just Changed the Future of Art

May 26, 2023

For close to 30 years—up until last week—courts have wrestled with the question of when artists can borrow from previous works by focusing in large part on whether the new work was “transformative”: whether it altered the first with “new expression, meaning or message” (in the words of a 1994 Supreme Court decision). In blockbuster case after blockbuster case involving major artists such as Jeff Koons and Richard Prince, lower courts repeatedly asked that question, even if they often reached disparate results.

But in a major decision last week involving Andy Warhol, the Supreme Court pushed this pillar of copyright law to the background. Instead, the Court shifted the consideration away from the artistic contribution of the new work, and focused instead on commercial concerns. By doing so, the Court’s Warhol decision will significantly limit the amount of borrowing from and building on previous works that artists can engage in.

The case involved 16 works Andy Warhol had created based on a copyrighted photograph taken in 1981 by celebrated rock and roll photographer Lynn Goldsmith of the musician Prince. While Goldsmith had disputed Warhol’s right to create these works, and by implication the rights of museums and collectors to display or sell them, the Supreme Court decided the case on a much narrower issue.

When Prince died in 2016, the Warhol Foundation (now standing in the artist’s shoes) had licensed one of Warhol’s silkscreens for the cover of a special Condé Nast magazine commemorating the musician. Explicitly expressing no opinion on the question of whether Warhol had been entitled to create the works in the first place, the Court ruled 7-2 that this specific licensing of the image was unlikely to be “fair use” under copyright law.

This is not necessarily a problematic result, given that Goldsmith also had a licensing market. Yet despite the Court’s attempt to limit itself to the narrow licensing issue instead of deciding whether Warhol’s creation of the original canvases was permissible, the reasoning of the decision has far broader and more troubling implications.

To know what’s at stake, it’s important to understand the fraught doctrine of “fair use,” which balances the rights of creators to control their works against the rights of the public and other creators to access and build on them.

What’s sometimes lost is in this discussion is that copyright law’s purpose (perhaps surprisingly) is to benefit the public—benefit to an individual artist is only incidental. The theory behind the law is that if we want a rich and vibrant culture, we must give artists copyright in their work to ensure they have economic incentives to create. But by the same logic, fair use recognizes that a vital culture also requires giving room to other artists to copy and transform copyrighted works, even if the original creator of those works objects. Otherwise, in the Supreme Court’s words, copyright law “would stifle the very creativity” it is meant to foster. Thus, to win a fair use claim, a new creator must show that her use of someone else’s copyrighted work advances the goals of copyright itself: to promote creativity.

Unfortunately, the Warhol decision took this already complex area of law and made it even more complicated. Lower courts and legal scholars will be fighting for years about its applications. But one thing is clear: it is now far riskier for an artist to borrow from previous work.

Not only did the Court downgrade the importance of whether a new work is transformative, whether it “adds something new and important” (to use the Supreme Court’s words from a previous case). The Court also painted a bizarre picture of Warhol as an inconsequential artist. Surely the Justices of the Supreme Court know that Warhol changed the course of art history. But the Warhol who emerges in the majority opinion is a tame portraitist whose work is just not that different from the photographs on which it is based.

In the Justices’ formulation, Warhol is a “style,” an artist whose “modest alterations” of the underlying photograph brought out a meaning that was already inherent in it, whose work portrayed Prince “somewhat differently” from Goldsmith’s image. Justice Elena Kagan, in a scathing dissent, charged that the majority had reduced Warhol to an Instagram filter.

Nowhere in the majority opinion would you recognize Warhol as a once-radical artist, the one de Kooning drunkenly approached at a cocktail party to utter, “You’re a killer of art, you’re a killer of beauty.” Nowhere does one see the Warhol whom philosopher Arthur Danto called “the nearest thing to aphilosophical genius the history of art has produced.” That Warhol is the paradigm of an artist who brings new “meaning and message” to the work he copies, the very kind of artist that the now-diminished emphasis on transformative use was meant to protect.

Of course, this decision is not just about Warhol. For that matter, it’s not just about other pop artists, or about appropriation artists.

Any artist who works with existing imagery should now reconsider her practice. Hire a lawyer, maybe try to negotiate a license and be ready to move on if you get turned away or can’t afford the fee. The safest and cheapest route—a consideration particularly relevant to younger artists and those who are not rich and famous—is to just steer clear of referencing existing work. Maybe that’s the right direction for art; maybe copying and relying on past work should be discouraged. But given the centrality of allusion, emulation, and copying to the history of art, it’s hard to imagine that’s a good thing. This is particularly so in contemporary digital culture, where, as I have argued, copying has taken on even greater urgency in creativity. But like it or not, these are not questions that artists, critics, and art audiences get to decide. The Supreme Court just changed the future of art.

https://www.artnews.com/art-in-america/columns/supreme-court-andy-warhol-decision-appropriation-artists-impact-1234669718/