The Trauma of Modern China ...and its impact on Post-Modern Japan

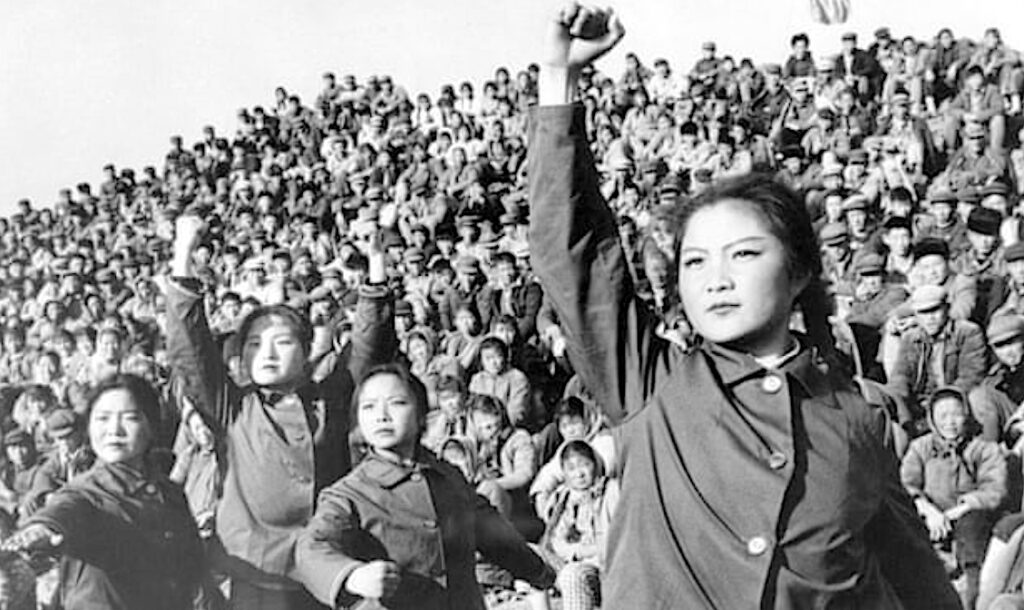

‘In the early stages of the Cultural Revolution, Red Guards – often teenage boys and girls – beat victims to death.’ Red Guard members pictured in 1966. Photograph: Universal History Archive/UIG/Getty Images

In West-Berlin I had been approached by fellow students to read die Mao Bibel.

Myself is the first person in the world, who published a text-photo-book on North- and South-Korea. In my book “Berlin, a winter’s tale after the wall”, essay by Wim Wenders, my point of view on former East Germany becomes crystal clear.

In the 80’s I took the Trans Siberian Railway from Berlin to Nakhodka (via Moscow, Irkutsk, Vladivostok).

In the same period, I travelled alone, by local train, in mainland China.

One of the best exercises to understand Chinese society is to observe the same person discuss “freely” the 2 million Chinese dead during the ‘Cultural Revolution’ with a fellow Chinese and right after that with a foreigner.

As a back-packer I travelled in the 90’s around South-East Asia.

Later I could visit Guam, Saipan and the Marshall Islands.

Here on ART+CULTURE I was not afraid in pointing out OE Kenzaburo’s problematic statement after his visit to China.

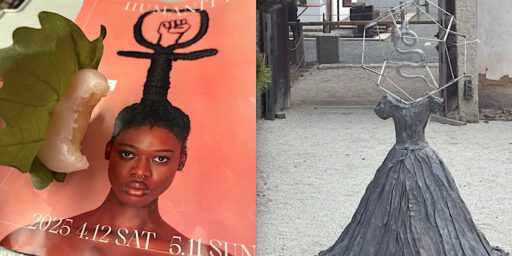

Lately, I have criticised the political agenda by fellow artist IIYAMA Yuki. As I was a soldier in the Bundeswehr, I’m wondering why my fellow artists fear of getting recruited via their “My Number” card. A war against China seems, in their view, imminent.

The funny thing is, that Japanese artists are extremely nationalistic. Japanese artists’ psychosomatic comparison with “Picasso” (THE reference in the so-called “Western Art”), who was partly of Arabic origin, with North African roots, and can NOT be called a WHITE painter, is the norm here in Japan.

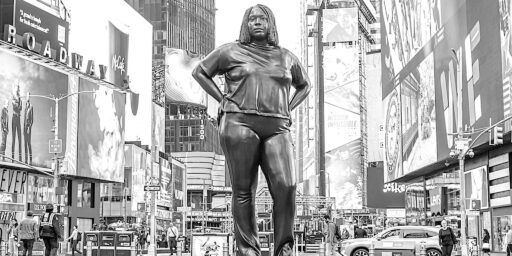

Feminism is been treated badly in Japan. A “Western” thing, they say.

Chinese and Koreans behave and act very nationalistic, too.

The ‘Chinese Trauma’ of the “Cultural Revolution”, the proper clarification of its implications is missing. Comparative studies between Japanese, North- and South-Korean and Chinese (Taiwanese) historians, a common (sense) language towards history writing: non-existent. A cat and mouse game by infantil Asian (mostly) men.

Mistrust and egocentrism between Asian neighbours predominate. Social behaviour between these Asian countries’ ordinary citizens completely divergent. The view about “a civilised person” and the “gender-related education” differs in each country. Racism? The norm.

To understand the highly problematic behaviour by Chinese in communicating with “same passport” Chinese, “not-same passport” Chinese, North Koreans, South Koreans, Japanese, “Zainichi” North-Koreans, “Zainichi” South-Koreans, “Zainichi” ‘Taiwan-Chinese’, “Zainichi” ‘Mainland-Chinese’, neighbouring South-East-Asians, “People of Colour, etc., etc. “, I recommend to read today’s critique by Tania Branigan about the actual Netflix film “3 Body Problem”.

For the academic reader, English speaking historian, I would like to recommend “Collective Killings in Rural China during the Cultural Revolution” by Yang Su (Cambridge, 2010).

Netflix’s 3 Body Problem is sci-fi. But beyond the alien threat lies the trauma of modern China | Tania Branigan

Though Liu Cixin’s revered trilogy has been westernised for TV, it dares to trace the scars of the Cultural Revolution

Wed 3 Apr 2024

It has brain-bending physics, mysterious visitors and futuristic technology. Yet viewers of the new Netflix sci-fi epic 3 Body Problem could be forgiven for some confusion as its opening scenes unfold. A drama about coming contact with aliens catapults us back to China in 1966, at the height of the Cultural Revolution: we see an eminent physicist viciously attacked by zealots before a howling crowd. As incongruous as it seems, this moment is central to understanding the book on which the show is based.

Liu Cixin’s The Three-Body Problem has been a multimillion-seller at home and abroad, earning praise from Barack Obama and others. The show takes liberties with the author’s text, replacing key characters with multiracial friends who studied physics together at Oxford to make it more “global” (read: more western). That’s annoyed many in China, despite Liu’s blessing. But the show is strikingly faithful to the historical scenes – and those scenes point to the lasting impact of this pivotal moment in China’s history.

The decade-long Cultural Revolution was a time of extraordinary violence and unpredictability: an estimated two million people died, from top political leaders to infants. Tens of millions more were hounded. In the early stages, Red Guards – often teenage boys and girls – beat victims to death. Revered scholars were prime targets. Some family members watched helplessly as victims suffered (like the physicist’s daughter); others betrayed their parents or spouses under pressure (like his wife). 3 Body Problem captures the sadism in its specific details, down to the humiliating dunce caps placed on victims’ heads and the excruciatingly painful “airplane” position that they were forced into: bent double with arms held out behind them.

The scene is central to the story that unfolds over Liu’s trilogy of novels. But it is more than just a way to drive the plot, or to humanise a key character. Liu grew up in the Cultural Revolution. As a young child, he was sent away to grandparents when his parents’ workplace was engulfed by fighting between warring factions.

Survivors I have met remain deeply scarred by what they witnessed, what was done to them and what they did to others. Those years bred profound cynicism and fear. The sense of an individual’s puniness against vast forces, and of an apparently hopeless existential struggle; an awareness of impossible moral choices; profound pessimism about human nature; a fixation on the importance of reason; the idea that speech is dangerous – all of these themes within Liu’s work are preoccupations shared by others who lived through the era. In the world he depicts, characters discover that generosity and humanity may not merely be irrelevant, but actively threatening to the one thing that counts – survival – as the scholar Chenchen Zhang discusses in a perceptive essay exploring why rightwing nationalists are among those who have embraced his work.

In the Chinese text, however, the historical scenes appear partway through: Liu has said that his publishers feared censors would take exception otherwise. While the Cultural Revolution is not utterly taboo in China, it is highly, and increasingly, sensitive. And neither the book nor the Netflix series refer to the movement’s origins: it was unleashed by Mao Zedong to reassert his political supremacy and, secondarily, to remould the people. Without that crucial context, which would not be tolerated in China, the Cultural Revolution is just a story of youthful fanaticism, human unreason and weakness.

Liu’s depiction of a civilisation alternating between stable and chaotic eras also evokes the widely shared fear of turmoil left by the events of the Sixties, ironically fostered by the party as a way of defending the political status quo. (He told one interviewer that “if China were to transform into a democracy, it would be hell on Earth”.) But instability and fragmentation are persistent anxieties throughout Chinese history, and in many ways the most obvious parallel for Liu’s central conflict is the confrontation between 19th century Qing dynasty China and the imperial powers whose advanced militaries allowed them to carve it up. What China calls the “century of humiliation” began with Britain and the opium wars and concluded with the end of the brutal Japanese occupation in 1945. Many Chinese readers also see an allegory of their country’s current struggle with the US as the two battle for technological superiority.

Chinese writers have addressed contemporary concerns through sci-fi for over a century. Like historical fiction, it allows them greater latitude, especially at a time of more stringent censorship. Of course, it does novelists a disservice to treat their work as a cypher: Liu stresses he is not using fiction to disguise a critique of the present. He is truly passionate about science – as his dense technical passages make clear – and has lived through extraordinary leaps in knowledge; he compares China’s recent flourishing in sci-fi to the “golden age” of the genre in America, where scientific innovations spurred authorial invention.

But while fiction doesn’t simply encode the real world, it does reflect and refract its concerns. (The book’s reiterated theme of ecological despoliation also makes the climate crisis loom large for the reader). Liu has written, of the Cultural Revolution and other childhood experiences, that “In this book, a man named ‘humanity’ confronts a disaster, and everything he demonstrates in the face of existence and annihilation undoubtedly has sources in the reality that I experienced.” His trilogy is rooted in the events of 1966, even as it stretches into a distant future.

• Tania Branigan is foreign leader writer for the Guardian and author of Red Memory: The Afterlives of China’s Cultural Revolution

ここに載せた写真とスクリーンショットは、すべて「好意によりクリエーティブ・コモン・センス」の文脈で、日本美術史の記録の為に発表致します。

Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial-NoDerivative Works

photos: cccs courtesy creative common sense