When will Nathan Drahi from Sotheby’s get out of Hong Kong? Patrick Drahi’s Extremely Capitalistic Way of Art Dealing And Speculating With Sotheby’s

注意!ATTENTION!

All pictures and texts have to be understood in the context of “Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial-NoDerivative Works.” ここに載せた画像やテクストは、すべて「好意によりクリエーティブ・コモン・センス」の文脈で、日本美術史の記録の為に発表致します。 Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial-NoDerivative Works, photos: cccs courtesy creative common sense

All these texts and pictures are for future archival purposes, in the context of Japanese art history writings.

Important update to understand the context.

As I proclaimed here on ART+CULTURE

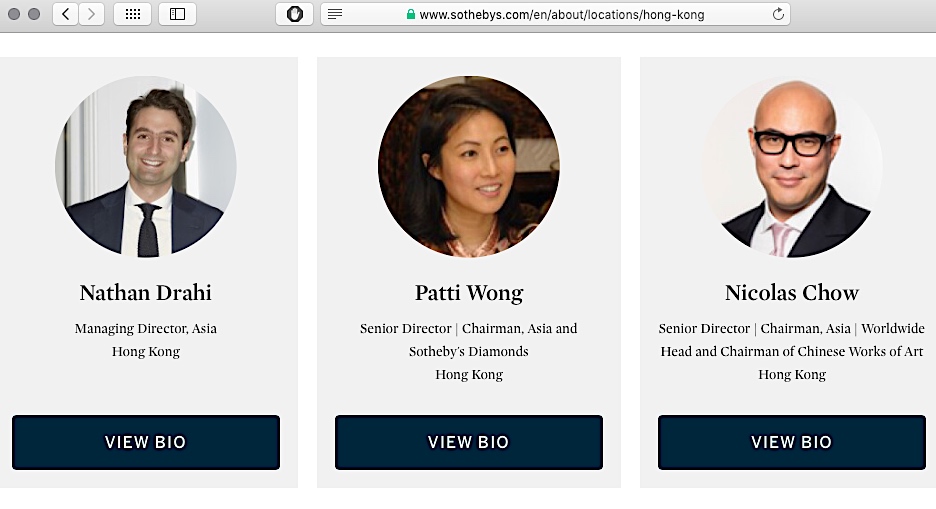

in 2022, Mr. Nathan Drahi was the wrong person to be CEO of Sotheby’s Asia in Hong Kong. Three years later, he has finally left Hong Kong.

Leaving a mess.

The following persons had been either “eliminated” by Sotheby’s or “rotated” for a lower salary:

Amy Cappellazzo

Kevin Ching

TERASE Yuki

Patti Wong

Brooke Lampley

Alex Branczik

Max Moore

Nathan Drahi

Felix Kwok

Hong Kong deserves better Asian art experts!

As a veteran artist in Japan, with quite idealistic opinions, it makes more and more difficult for me to agree with the actual tendencies of the global art world.

Two examples:

1) I am against the so-called “NFT works” by digital illustrators, like Beeple, to be recognised as art works, put into the canon of art history.

Check:

#USABS U.S. ARTY BULL SHIT. NFTデジタル・アーティスト ビープル:「美術史の流れを変えたい」や「悪役である」というメリット

#USABS。NFT Digital Artist Beeple: “I want to change the course of art history” and the merit of “being the bad guy”

https://art-culture.world/articles/nft-beeple-digital-artist-ビープル/

2) Every auctioneer applauded when Christie’s and Sotheby’s became private enterprises, so a more long-term strategy, not quarterly results, would benefit everyone involved.

At the moment, Christie’s Pinault’s engagements as a collector should be applauded. Showing his marvellous collection in different places around Europe is a win-win situation for all of us art lovers.

Check this out:

フランソワ・ピノーの三番目の刺激的な現代美術館、再建築 by 安藤忠雄

Exciting 3rd Contemporary Art Museum for François Pinault, rebuild by ANDO Tadao

https://art-culture.world/articles/francois-pinault-art-museum/

原口典之と関根伸夫のアート実践を考える

Thoughts on the artistic practice of HARAGUCHI Noriyuki and SEKINE Nobuo

https://art-culture.world/articles/haraguchi-noriyuki-sekine-nobuo-原口典之-関根伸夫/

現代美術コレクター、兼オークションハウス・クリスティーズ社長フランソワ・ピノー氏のコレクション展 in モナコ公国

Contemporary Art Collector, Christie’s Auction House Owner François Pinault Shows His Collection In The Principality of Monaco

https://art-culture.world/articles/pinault-collection-ピノー・コレクション/

However, Patrick Drahi demonstrated that he doesn’t like art. What a shame. A disaster for the Asian art market, too, with his amateurish, spoilt son Nathan Drahi, who is the wrong person in Hong Kong’s Sotheby’s.

Check this out:

Sotheby’s Harsh Reshuffle: After Amy Cappellazzo and Kevin Ching, Next Prominent Figure TERASE Yuki Bites the Dust

サザビーズのコンテンポラリーアート部門アジア地区部長・寺瀬由紀氏を巡って

https://art-culture.world/articles/terase-yuki-寺瀬由紀/

up-date 2024/6/26

From Sotheby’s: “After spending 3 years in HK leading the Modern & Contemporary art business in Asia and promoting an ever greater global integration of artists and collectors in the region, Alex Branczik and Max Moore will return to London and NY respectively, from October”.

https://x.com/enidtsui/status/1805824998441205839

(end of up-date)

Next One @ Sotheby’s: Hugely Popular Amy Cappellazzo Bites the Dust

What will happen @ Sotheby’s Japan?

https://art-culture.world/articles/amy-cappellazzo/

アジアのアートマーケットの中心的人物:26歳のネイサン ドライ氏、新CEO サザビーズアジア (サザビーズのオーナー パトリック・ドライの息子)

Key Person of Asia’s Art Market: 26 Years Old Nathan Drahi, New CEO Sotheby’s Asia (Son of Sotheby’s Owner Patrick Drahi)

https://art-culture.world/articles/key-person-of-asia-art-market/

Hong Kong Spring Luxury Sales | A Virtual Exhibition Tour

Link_as_archive_https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9JZ28D2I4e4

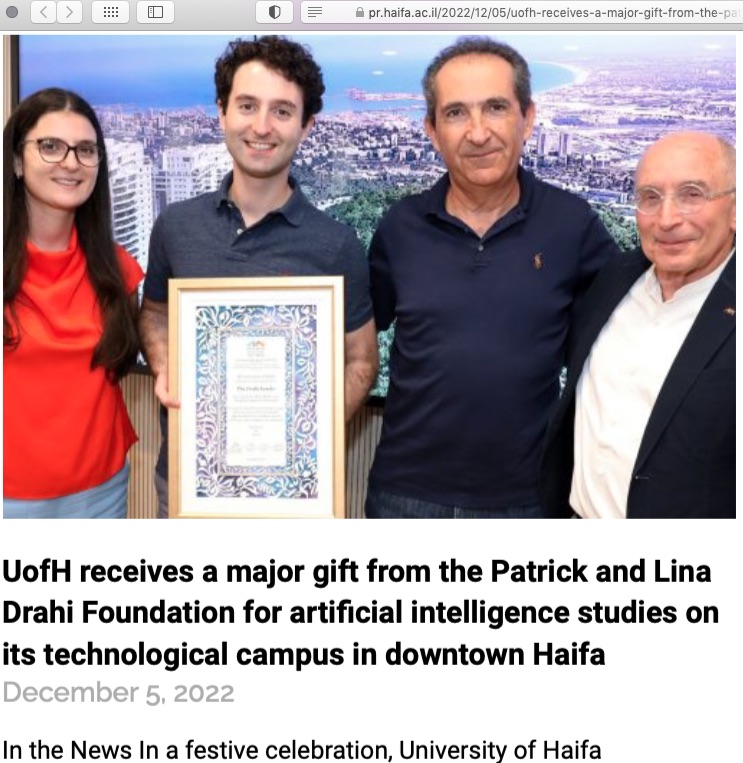

French-Israeli telecoms billionaire Patrick Drahi has selected Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley to pursue the IPO for around 5 billion US Dollars.

Check:

https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2022/01/13/sothebys-selects-banks-initial-public-offering-five-billion

Means, Drahi would make a profit of around 1.3 billion US Dollars in just 3 years. Let’s say it bluntly: we artists feel annoyed, we’re just being fucked by the Drahi’s family.

I really hope, that young and unsympathetic Nathan Drahi will part from Hong Kong as soon as possible.

Up-date 2022/12/8:

Sotheby’s Chairman Patti Wong, Who Ushered House’s Growth in Asia, To Depart

ANGELICA VILLA, December 7, 2022

https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/sothebys-international-chairman-patti-wong-to-depart-1234649457/

Patti Wong, the Retiring Sotheby’s Rainmaker Who Made Hong Kong an Auction Mecca, Reflects on Asia’s Rise as a Market Powerhouse

In this exclusive interview with Patti Wong, the 30-year auction house veteran charts the rise of Asia and discusses how Hong Kong became an auction hub.

https://news.artnet.com/market/pro-qanda-patti-wong-sothebys-asia-2237659

up-date 2024/4/25

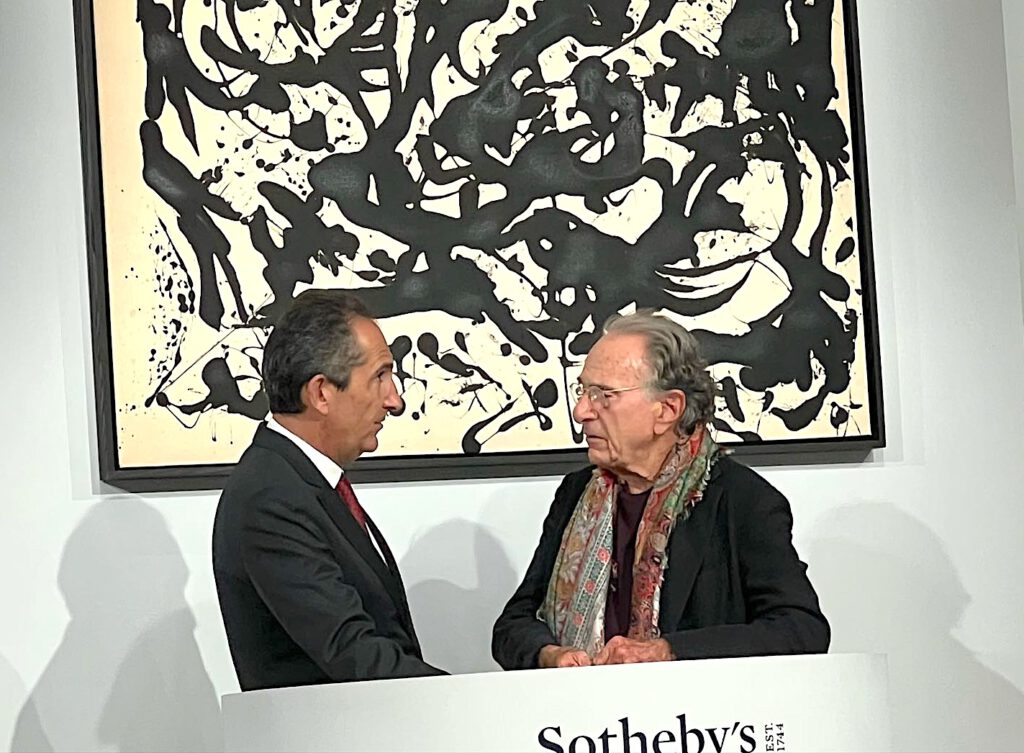

Daryl Wickstrom, Patti Wong and Philip Hoffman

PATTI WONG & ASSOCIATES

Previously, Patti Wong served as the International Chairman of Sotheby’s Worldwide and Chairman of Sotheby’s Asia. During her more than 30 years at the auction house, Patti played a leading role in the development of the art market in Asia, building some of the most significant collections in the region. Daryl Wickstrom, Patti’s business partner, spent more than 20 years at Sotheby’s, focusing on key growth areas, including Asia, where he was based for seven years during a time of exponential growth in the region. Patti and Daryl will be joined by a talented team of specialists and support personnel from around the world. Lisa Chow, another Sotheby’s veteran of 20 years, will serve as the firm’s Managing Director.

Source_https://twitter.com/enidtsui/status/1783519602871263457/photo/1

(End of up-date)

Up-date 2023/8/11

Billionaire Drahi vows speedy asset sales to cut debt at Altice

August 8, 2023

Summary

– Altice France pledges to do “whatever it takes” to cut debt

– Mentions sale of non-core assets, such as data centres

– Aims to raise about 3 billion euros – Drahi

– Partnerships, cash from other businesses among options – Drahi

PARIS, Aug 8 – French-Israeli billionaire Patrick Drahi vowed on Tuesday to slash debts at Altice France, home to the country’s second-biggest telecoms operator, by selling assets within a year.

Drahi, under pressure after his right-hand man was arrested over allegations of corruption, is striving to boost creditors’ confidence in the financial reliability of his sprawling media-to-cable empire, whose combined debts total $60 billion.

At Altice France, one the three separate entities composing the Altice group, falling sales and core operating profits in the second quarter have added to the concerns, with net debt rising close to 24 billion euros ($26 billion).

Assets will be sold within Altice France or outside France to repay debt, Drahi told investors on a conference call.

“(The aims is) to raise, one way or another, 3 billion (euros) of equity, plus or minus,” Drahi said.

“We have lots of options: one, is asset disposals, bringing cash; two, lot of people are calling to be partners with us; and three, bringing cash from our other businesses,” Drahi added, as analysts pressed him to provide details on the deleveraging plan.

Altice France’s net leverage ratio at end of June was 6.3 times its yearly core operating profits.

There are active discussions for the potential sale of Altice France’s date centres, senior adviser Dennis Okhuijsen said on the same call, adding he was confident about giving an update on potential sales during third quarter results.

In its second quarter earnings presentation on Tuesday, Altice France, home to France’s second-biggest telecoms firm SFR, said it would do “whatever it takes” to reduce leverage.

Altice France’s net debt was close to 24 billion euros at the end of June, up from 23.6 billion at end of March, the group said.

It posted a 5.7% fall in core operating profits in the second quarter. Total earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation (EBITDA) fell to 1.02 billion euros from 1.08 billion euros a year earlier. Total revenues fell by 2.6% to 2.77 billion euros.

Drahi told investors on Monday he felt “shocked” and “betrayed” by an ongoing corruption probe at its Portuguese unit Altice Portugal

Altice’s co-founder Armando Pereira was placed under house arrest in Portugal last month while an investigation is conducted. Pereira has denied any wrongdoing.

($1 = 0.9141 euros)

https://www.reuters.com/business/media-telecom/billionaire-drahi-vows-speedy-asset-sales-cut-debt-altice-2023-08-08/

Factbox: A breakdown of Patrick Drahi’s $60 billion debt at Altice

August 8, 2023

PARIS, Aug 8 – French-Israeli billionaire Patrick Drahi is facing renewed questions over the $60 billion pile of debt that allowed him to build his media and telecoms empire, after a corruption probe targeting his most trusted lieutenant shook his Altice group.

Spread across three separate entities, all controlled by Drahi, parts of the debt will soon have to be refinanced and maturities extended in the context of rising interest rates.

The debt burden is distributed as follows:

ALTICE INTERNATIONAL: net debt of 8.6 billion euros ($9.45 billion) at end of June.

* The smallest of the three Altice group entities is home to Portugal’s biggest telecoms firm and has a net leverage ratio of 4.8 times core operating profits.

* The unit is at the centre of a corruption probe in Portugal which led to right-hand man and Altice co-founder Armando Pereira being placed under house arrest last month.

* Altice International faces large maturities starting in 2025 and amounting to 2.13 billion euros in 2027 alone.

* Moody’s, which cut Altice International’s long-term debt rating to B3 from B2 in June, said last month that the probe created “uncertainty that is likely to affect investors’ confidence” as the group faces close to 800 million euros of debt repayment in 2025.

* S&P revised its outlook on the entity from negative to stable in April after Altice International posted “solid” growth in sales and core operating profits.

ALTICE FRANCE: net debt of 23.9 billion euros ($26.17 billion) at end of June.

* Home to France’s second-biggest telecoms firm SFR, Altice France’s debt reflects net leverage of 6.3 times the entity’s yearly core operating profits.

* The next sizable repayment is due in 2025, with 1.64 billion euros worth of secured bonds and secured loans.

* The biggest maturities are due from 2027, starting with 5.4 billion euros of repayments and peaking at 9 billion euros the year after.

* S&P and Moody’s both recently downgraded Altice France’s long-term debt rating, respectively to B- and B3 within the speculative range, citing the higher cost of refinancing in a context of rising interest rates and a weaker than expected operating performance.

ALTICE USA: consolidated net debt of $24.5 billion at end of June

* The New York-listed Altice entity has the highest net leverage ratio of the three, at 6.8 times its core operating profits at end of June.

* The next sizable maturity is due in 2025 with $1.6 billion worth of debt to be repaid then, before the $6 billion and $5.4 billion of repayments due in 2027 and 2028 respectively.

* S&P downgraded Altice USA’s long-term debt rating three times in less than a year, lastly to B from B+ in March. The credit rating firm warned it could lower the rating further if the net leverage ratio rose above 7 times core operating profits or if free operating cash flow turned negative.

https://www.reuters.com/business/media-telecom/breakdown-patrick-drahis-60-billion-debt-altice-2023-08-08/

up-date 2024/3/5

What’s Another $25 Billion on $100 Billion of Debt?

A potential deal between Charter and Altice USA would create a highly leveraged cable player. But the alternatives for both firms could be worse.

March 5, 2024

An ambitious deal may be brewing in the US cable industry, creating a behemoth carrying nearly $125 billion of debt. If Spectrum Internet owner Charter Communications Inc. wants to formalize a takeover of billionaire Patrick Drahi’s Altice USA Inc., it needs to be sure the benefits are worth the considerable financial stretch. The dilemma is that passing on a transaction carries risks of a different kind.

Charter’s stock and bond investors reacted nervously last month when Bloomberg News reported that management was weighing an offer for the US slice of Drahi’s telecoms empire. The company already carries nearly $100 billion of net debt. Its main shareholder is Liberty Broadband Corp., a vehicle of cable tycoon John Malone, himself no stranger to leverage.

more @

https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2024-03-05/drahi-s-altice-and-charter-cable-deal-may-be-worth-the-debt?

2024/4/10 up-date:

Financial engineering to dig into the pocket change and reduce debt cost!

Sotheby’s, the auction house owned by telecom billionaire Patrick Drahi, plans to borrow about $500 million through bonds backed by personal loans made to art collectors

By Charles E Williams and Carmen Arroyo

Bloomberg, April 9, 2024

Sotheby’s Plans $500 Million Bond Sale Secured by Art, Collectibles

– Barclays may start premarketing process as soon as Wednesday

– More issuers have been pursuing niche types of securitizations

Sotheby’s, the auction house owned by telecom billionaire Patrick Drahi, plans to borrow about $500 million through bonds backed by personal loans made to art collectors.

Barclays Plc is the sole structuring agent of the asset-backed security and may start premarketing the deal as soon as Wednesday, according to people with knowledge of the matter. BNP Paribas SA and Morgan Stanley are also joint leads on the transaction, according to a company filing.

more @

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-04-09/patrick-drahi-s-auction-house-sotheby-s-plans-securitized-bond-sale

Billionaire Drahi Leaves Creditors Flummoxed With His ‘Bully-Boy’ Moves

Drahi risks burning bridges with creditors, who over decades bankrolled his debt-fueled empire-building, creating one of Europe’s most leveraged companies.

By Benoit Berthelot and Irene Garcia Perez

Bloomberg, April 10, 2024

Patrick Drahi was uncharacteristically chatty on that mild March day at the headquarters of his flagship company Altice France in the south of Paris. The tycoon had just agreed to sell his media operations to fellow French billionaire Rodolphe Saadé for €1.55 billion ($1.68 billion), and was bidding adieu to managers and anchors of the news channel BFMTV.

Over bite-sized appetizers and sparkling water in a bright, glass meeting room overlooking a terrace, he told them he decided in July to cash in on the news channel, after Altice co-founder Armando Pereira was arrested in Portugal for alleged corruption. “When you have an apartment, and you realize the bathroom is worth more than the whole apartment, what do you do?” Drahi asked. He went on say that he’s been thinking about his succession and decided to start selling chunks of his empire, including the French media business, because his four kids told him they want to invest in other areas, according to people who were present but didn’t want to be identified describing a private event.

2024/5/4 up-date:

Smart Money’s Appetite for Art-Backed Debt Investing: Sotheby’s Announces $700M Art Loan Securitization to High Demand

As alternative investments gain popularity among private clients, fine art is quietly emerging as a favorite asset class.

By Rebecca Fine

These days, it seems like every asset manager is offering advice to their private clients about how to build a portfolio of alternatives. J.P. Morgan says the typical range among their private bank clients is 15 percent to 30 percent of their overall portfolio. “That said, some clients with significant resources and an inclination to plan multi-generationally do allocate 50 percent or more to alternatives; much like some large endowments.” Blackrock advises incorporating private credit, and Goldman Sachs Asset Management says the conversation has shifted from the “case for investing in alternatives” to “how to invest in alternatives.”

Art investment is a favorite of the ultra-high-net-worth and their banks

As alternative investments gain popularity among private clients, one asset class is quietly emerging as a favorite: fine art. Increasingly, ultra-high-net-worth (UHNW) individuals are leveraging their art collections to access liquidity and diversify their portfolios. For an asset class that has not been traditionally viewed as a staple of an overall portfolio, this may come as a surprise. According to Deloitte, 84 percent of UHNW and high-net-worth (HNW) clients have a significant portion of their overall wealth invested in art. Sixty-three percent of wealth managers (in private banks and family offices) have integrated art into their wealth management offerings, according to a Deloitte survey in 2023.

Their private banks have a history of investing in art that dates back to the Renaissance, when Italian bank Monte dei Paschi di Siena began building its corporate art collection in 1472. Financial institutions like Deutsche Bank, JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America, have world-renowned art collections; UBS counts 30,000 artworks in its collection.

Art collectors are increasingly using art financing

Collectors buy art they fall in love with, made by artists whose artworks and messages resonate with them. But because primary prices are so high, they can’t (and don’t generally) ignore the fact that it is also an investment. Traditionally, art collectors have viewed their acquisitions as long-term investments, tying up significant capital in illiquid assets. Resales are sometimes not even a real consideration. However, a growing number of financially sophisticated collectors are realizing that the equity hanging on their walls can be unlocked and redeployed—without having to sell treasured pieces. This is where art financing comes in.

Art loans are available from several private banks, certain auction houses and specialist art lenders (including Athena Art Finance). I wrote for the 2023 Deloitte Private and ArtTactic Art & Finance Report about the myriad reasons clients take out art-secured loans, the growth and the evolution of the art lending market. Even as credit markets have tightened, art lending has proliferated. Sotheby’s Financial Service, which began lending in 1988, stated recently that its art loan portfolio grew more than 100 percent over the last two years and is at its highest-ever portfolio balance.

Art-backed debt is an attractive portfolio diversifier and a way to earn passive income

Having bundled portfolios of art-backed loans for investors for more than five years, Yieldstreet has been waiting for the broader market to take notice. Moreover, given art’s low correlation to many important asset classes, it is an ideal choice for portfolio diversification, as long as the underlying loans are carefully underwritten and serviced by experienced art finance professionals.

A year ago, in Reasons to Love Investing in Art-Backed Debt, I explained how portfolios of art-backed debt offer investors an uncorrelated asset class with attractive yields and solid principal protection—without the costs associated with owning physical art or concerns of whether the art will appreciate in value over time. Then, in The Holy Grail for Passive Income: Art-Debt Investing, I took a deeper dive into the fundamentals of art-debt investing, focusing on the types of questions that investors should ask as they consider these investments to earn passive income.

Now, with Sotheby’s Financial Services’ historic $700 million securitization of its art loan portfolio, art debt has come into its own as an investable asset with a public rating.

On April 23, Sotheby’s Financial Services launched a securitization program consisting of $700 million of asset-backed notes backed by art-secured loans. Sotheby’s securitization of its art loan book is a landmark in art’s financialization, transforming what was otherwise perceived as a less illiquid and non-income-producing asset into an institutionalized financial product. It is a powerful demonstration of the great demand for art financing and it puts to bed questions about whether art is a credible asset class. As managers for pension funds, endowments and family offices demonstrated their excitement to finally incorporate art into their investment portfolios, Sotheby’s quickly increased its offering from $500 million to $700 million to match the intense demand.

At a high level, securitization is a financial process whereby contractual debt obligations (here, art-backed loans) are pooled together to be repackaged into interest-bearing securities and then sold to institutional investors. The techniques used to mitigate the credit risk profile of asset-backed securities (e.g., over-collateralization or structuring into tranches that reflect the credit quality of the underlying assets and the attendant risks), the many parties involved in securitization and the reasons originators seek to securitize its assets are beyond the scope of this article.

How did the credit ratings agency get comfortable with this new asset class?

In the Sotheby’s pre-sale document from the ratings agency, Morningstar DBRS, they explained a number of key considerations (which closely track my prior article for Observer):

Track record of the art lender: While the ratings agency did not comment on specifics around Sotheby’s underwriting of the binary risks associated with lending against fine art (such as title, authenticity, attribution), the ratings agency explained that it got comfortable with a 10-year look back at loan performance during economic cycles, including a corporate earnings recession from 2014-15, and the financial crisis of 2007-09. “What we found is that the performance has generally been fairly consistent,” said Doo-Sik Nam, a senior vice president for U.S. asset-backed securities credit ratings at Morningstar DBRS.

Valuations of the art collateral: Morningstar DBRS gained comfort with 10-plus years of auction data, detailing the way that Sotheby’s Financial Services evaluates art and determines high and low estimates for individual works.

Characteristics of the portfolio and diversification as a risk mitigant: According to Morningstar DBRS, the portfolio, valued at $1.4 billion, is comprised of 89 loans that are secured by 2,484 works of fine art and collectibles. By genre, the breakdown is as follows: 43 percent of the collateral is in Contemporary Art, 21 percent is Old Master paintings, 15.57 percent is Impressionist and Modern Art, 5.25 percent is Latin American Impressionist and 3.72 percent is Chinese works of art. According to Bloomberg, one third of the portfolio consists of artworks by the following five artists: Rembrandt, Warhol, Picasso, Basquiat and Kahlo. It has also been reported that the collateral includes “collectibles, design furniture, coins, books, jewelry, watches, wine or other spirits”. Investors can learn more about the portfolio from the offering materials (for example, borrower concentrations, artwork concentrations, artist concentrations, etc.).

Saleability and liquidity of the art loan collateral: It is worth noting here that, as an auction house, Sotheby’s is also the sales agent in the event of a default, which greatly facilitates liquidation.

Sotheby’s securitization program is not the first time that investors have been able to invest in diversified portfolios of art-backed loans

While Sotheby’s bonds are available only to institutional investors (such as pension funds and endowments), for more than five years, Yieldstreet has been offering accredited investors (individuals who meet certain wealth and income thresholds) access to diversified portfolios of the art-backed loans underwritten by Athena Art Finance, with minimums as low as $10,000. Since 2019, Yieldstreet has launched eight art debt funds, five of which have fully matured.

Yieldstreet’s art debt offerings provide an opportunity for individual investors to participate in highly diversified portfolios of art-secured loans. Yieldstreet investors receive monthly passive income through notes that synthetically link to the underlying borrowers’ payments of interest and principal. Like Sotheby’s offering, the diversified art-debt offerings consist of pools of art-backed loans, and as such, investors are not investing directly in artworks. What’s more, these investments specifically do not depend on any appreciation of the artworks’ values.

In the coming years, as UHNW collectors increasingly use leverage to grow their collections and recapitalize their investments in art, I expect that art-debt investment offerings will proliferate in an effort to meet the insatiable demand of savvy investors seeking access to the rarified world of art finance.

A lot of ink will be spilled about investing in art-backed debt portfolios; remember you heard it here first…

Rebecca Fine is the CEO of global art lender, Athena Art Finance, and the Managing Director of Art Investments at Yieldstreet, a private market alternative investments platform. She has over 25 years of experience in the art market and art finance.

https://observer.com/2024/05/smart-moneys-appetite-for-art-backed-debt-investing-sothebys-announces-700m-art-loan-securitization-to-high-demand/

Up-date 2024/5/23

After Kevin Ching, Amy Cappellazzo, Yuki Terase, Patti Wong, Sotheby’s looses also Brooke Lampley, who heads to Gagosian

Switching from an Auction House to a Commercial Gallery

https://art-culture.world/articles/brooke-lampley/

Up-date 2024/5/29

Sotheby’s Will Reportedly Lay Off Dozens of Employees in the UK

May 29, 2024

quotes:

The house is reportedly set to cut around 50 employees based in London, and per the Art Newspaper, similar layoffs may follow in New York and at other Sotheby’s locations in Europe.

A Sotheby’s representative did not immediately respond to request for comment on the Art Newspaper report, which stated that the auction house had entered a “consultation period” in which it would evaluate its financial future.

…

Last year, Sotheby’s laid off at least 10 senior employees, a cutback that also seemed to coincide with the departure of at least four people involved in NFT-related sales.

Since 2019, Sotheby’s has been held privately by Patrick Drahi. In the past few years, however, there have been rumors of possible financial changes at the auction house, including a potential plan to take Sotheby’s public once again that first made the press in 2021.

full text:

https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/sothebys-layoffs-uk-report-1234708237

2024/7/10 up-date:

Sotheby’s hands huge pay day to billionaire owner Patrick Drahi

10 July 2024

Sotheby’s paid a huge dividend to its billionaire owner Patrick Drahi despite a tick down in its financial performance amid reports a minority stake could be sold to ease debt concerns.

The UK arm of the auctions giant has paid £66m in dividends, according to newly-filed documents with Companies House, as its turnover and pre-tax profit dipped during its latest financial year.

The results show the Sotheby’s UK division reported a turnover of £144.8m for 2023, down from £150.9m.

Auction sales fell from £131.3m to £125.8m while private sales dipped slightly from £19.5m to £19m.

Sotheby’s pre-tax profit also went from £29.9m to £27.2m over the same period.

A dividend of £41m was paid during the year while £25m was paid in June 2024.

Sotheby’s was acquired in 2019 by French telecommunications billionaire Patrick Drahi through his company Bidfair for $3.7bn.

In a statement signed off by the board, Sotheby’s said: “The directors are satisfied with Sotheby’s result in 2023.

“The directors remain confident of Sotheby’s long-term success and continue to selectively invest in global initiatives.”

The results come after reports emerged towards the end of 2023 that bankers had sounded out potential buyers for a minority stake in Sotheby’s.

Drahi has come under pressure to sell assets at his indebted telecoms group Altice while those approached have included European billionaires and the Qatar Investment Authority, according to the FT.

The business was established in 1744 in London by Samuel Bake and is now headquartered in New York.

https://www.cityam.com/sothebys-hands-huge-pay-day-to-billionaire-owner-patrick-drahi/

up-date 2024/8/10

2024/8/9 ARTnews

Abu Dhabi Sovereign Wealth Fund to Acquire Minority Stake in Sotheby’s in $1 Billion Investment Deal

quotes:

“The additional capital and investment expertise will enable us to accelerate our strategic initiatives, expand our commitment to excellence in the art and luxury markets, and continue to innovate to better serve our clients around the world,” Sotheby’s CEO Charles Stewart said in a press release.

ADQ is a prominent sovereign wealth fund based in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates. It was established in 2018 as Abu Dhabi Developmental Holding Company (ADDH) and rebranded to ADQ in 2020. The partnership marks ADQ’s first venture into the cultural sector, reflecting its strategy of diversification and its commitment to bolstering arts and culture domestically. The involvement of ADQ, a major Middle Eastern player, is expected to further solidify Sotheby’s presence in the region, which is one of the fastest-growing markets for art and luxury.

up-date 2024/8/31

Sotheby’s earnings plunge as art market catches a chill

Arch-rival Christie’s also suffering from slowdown in auctions

Sotheby’s has reported an 88 per cent plunge in its core earnings and a 25 per cent decline in auction sales, as a chill in the art market hits one of the industry’s most famous brokers.

The first-half figures at Sotheby’s main auction business reveal the extent of the financial pressure the group came under before it struck an investment deal with Abu Dhabi earlier this month.

Weaker luxury spending in China is among the factors weighing on demand for fine art and affecting both Sotheby’s and historic rival Christie’s.

One of Sotheby’s marquee auctions fell short of expectations in May, when the winning bid for a Francis Bacon portrait of his lover George Dyer missed the low end of its $30mn-$50mn estimate.

Abu Dhabi-based sovereign wealth fund ADQ agreed to take a minority stake in the auction house earlier this month, through a $1bn capital raise funded with its present owner Franco-Israeli billionaire Patrick Drahi, who has been looking to cut debt across his business empire.

Ahead of the deal, Sotheby’s told lenders that its earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation (Ebitda) plunged 88 per cent to just $18.1mn in the first half of 2024. Even after it stripped out further costs — such as severance pay and legal settlements — from this earnings measure, Sotheby’s adjusted Ebitda fell 60 per cent to $67.4mn.

It also booked $558.5mn of revenue in the first six months of 2024, a 22 per cent fall on the $712.3mn recorded in the same period last year, according to an earnings report shared with its lenders.

The results cover Sotheby’s main auction business and do not include earnings generated under other arms of parent company BidFair, such as its financial services division that makes loans to art collectors.

Sotheby’s declined to comment.

The slowdown at Sotheby’s follows Christie’s last month publicly reporting a similar 22 per cent drop in auction sales over the same period.

Sotheby’s results also reveal that it intends to use $700mn from the planned capital raise to “reduce the company’s leverage”, with the deal with ADQ expected to close in the fourth quarter of 2024.

Founded in 2018, the ADQ sovereign wealth fund is tasked with fuelling development in the oil-rich emirate of Abu Dhabi and is chaired by the UAE’s powerful national security adviser, Sheikh Tahnoon bin Zayed al-Nahyan. An Abu Dhabi branch of the Louvre museum opened in 2017.

Sotheby’s reported more than $1.8bn of net “long-term debt” at the end of June, suggesting that it will still carry over $1bn of such debt even after the capital raise is completed. The company’s total liabilities stand at $4.3bn.

The wider Sotheby’s group has also borrowed money through creative means this year, with its financial services affiliate in April raising $700mn through new bonds backed by loans the auction house provides to art collectors.

Drahi took over Sotheby’s in a leveraged buyout in 2019, returning the centuries-old auction house to private ownership three decades after it listed on the New York stock market and bringing him into direct competition with French billionaire François Pinault, who owns Christie’s.

The deal handed Drahi a trophy asset alongside his Altice business empire, which he transformed from a niche cable company into a global telecoms conglomerate through a decade-long acquisition spree.

Now faced with rising interest rates and market jitters over a criminal probe into one of Altice’s co-founders, Drahi has been increasingly selling off assets in a bid to tackle his group’s over $60bn debt pile.

Earlier this month, Drahi agreed to sell a stake of nearly 25 per cent in BT Group to Indian billionaire Sunil Bharti Mittal’s conglomerate, having borrowed heavily from banks to buy up shares in the British telecoms operator in previous years.

https://www.ft.com/content/89fd2c65-0dfd-4f3b-b357-95d1c83c92c9

2024/9/26 up-date:

Can Sotheby’s CEO Charles Stewart Get the 280-Year-Old Auction House in Order?

ARTnews, September 23, 2024

https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/sothebys-future-charles-stewart-1234718148/

Quotes:

In his Puck newsletter, Wall Power, art market journalist Marion Maneker quoted an “old hand” in the business: “No one who has ever sold art would have come up with that plan.” And in a way, that’s right. The plan came from Sotheby’s CEO Charles F. Stewart, a former investment banker who, until he took the top job five years ago, was as removed from the art world as Paris is from Hong Kong.

—

Stewart has none of those art world bona fides. As a senior at Yale majoring in history, with a bit of squash and a capella singing on the side, he had done some teaching in Australia when he learned about a former classmate who was working with an investment banking firm that had business in Brazil. This piqued his interest. “When I was in your position, I really had no idea what i-banking was,” Stewart told a group of students at his alma mater in 2007, “other than the notion that it involved a massive sellout.”

…

There, he also oversaw all activities in EMEA, Asia, and North America. On the surface, none of this makes for an auction house chief executive pedigree, but Stewart says investment banking has served as a proving ground for the kind of dealmaking and relationship-building that sets the art market atingle.

“The high end of Wall Street and the high end of the art world have a lot in common,” Stewart told me over smoked trout crêpes, creamed spätzle, and a plate of roasted bratwurst and sauerkraut at Café Sabarsky, the Viennese café–style restaurant in New York’s Neue Galerie.

…

“Both in terms of the clients they serve, which are often the same, but also the business model. Investment banking is a global professional services business where the goal is to win by building trust-based relationships with clients. If you close your eyes and put the arts and objects aside, it’s not dissimilar from being selected to lead an IPO. The only difference is, you’re not dealing with someone’s company. This is something more personal. More intimate. Collectors collect out of passion.”

…

Four years later, in 2019, Drahi bought Sotheby’s, in a deal worth $3.7 billion, with $2.6 billion or so in cash and, in typical Drahi fashion, a fair share of debt. Sotheby’s shareholders got about $57 per share, a 61 percent bump in the stock price. “Sotheby’s is one of the most elegant and aspirational brands in the world,” Drahi said in a statement at the time of the purchase, calling himself “a longtime client and lifetime admirer of the company.”

The purchase mystified art world insiders, to whom Drahi was mostly unknown despite his passion for collecting modern and Impressionist artworks. “Most people don’t seem to know who he is,” art dealer and former Christie’s executive Brett Gorvy told the New York Times. “He’s not a Pinault in terms of his level of buying,” Gorvy added, comparing Drahi’s buying habit to that of the French billionaire François Pinault, owner of the luxury brand behemoth Kering (Gucci, Balenciaga, Bottega Veneta, and Yves Saint Laurent, among others), and Sotheby’s main competitor, Christie’s.

…

This has caused more than a few art market powerbrokers and prognosticators to predict that Drahi would someday be selling Sotheby’s, a prospect Stewart is quick to refute. “I want to be super clear on this and I can speak for myself, for Sotheby’s, and I think for Patrick: Sotheby’s is not in any way for sale, nor is it something that Patrick would ever consider selling. There have been some rumors about it, and when it comes up we generally don’t comment.” For an outside perspective, I asked Marc Glimcher, CEO of market behemoth Pace Gallery, whether he thought Drahi might put Sotheby’s up for sale. “It’s one of the most recognized brands in the world,” he said. “Simply irreplaceable. If Patrick wanted to sell it whole, it would already be sold.”

—

The most apparent was the full-hearted embrace of online only sales, which started at the auction house in 2016, but were often seen as auxiliary. “The conventional wisdom was that online sales were second-tier at best, third-tier more likely, and it became a self-fulfilling prophecy,” Stewart said. The best works weren’t presented online, which often served as a signal to sellers that they shouldn’t be online. Covid changed that. “The levels at which people are willing to bid online for works of art, we must have broken our own record every month for a year. In November 2020 we had a bid at $50- or $60-plus million on our app. It’s really remarkable.” (That season someone entered a $73.1 million bid for Francis Bacon’s Triptych Inspired by the Oresteia of Aeschylus via the Sotheby’s app. It ultimately sold for more than $84.5 million.)

—

The luxury market is far larger than the art market. The Art Basel & UBS Art Market Report 2024 puts the global art market at around $65 billion, of which Sotheby’s in 2023 reported gross sales of $7.9 billion, about 12 percent. Take away revenue from ancillary businesses like RM Auction and Concierge and the percentage is 10. The global luxury market, on the other hand, was projected to be worth $1.6 trillion last year. The increased focus on luxury is bolstered by an upgrade to Sotheby’s brick-and-mortar locations, and by a new media wing led by Kristina O’Neill, former editor-in-chief of WSJ. Magazine, who will relaunch Sotheby’s Magazine. The auction house in Paris relocated this year to the former home of the historic Galerie Bernheim-Jeune in the 8th arrondissement. It boasts a wine cellar and tasting area, and spaces for concerts, fashion shows, and lavish dinners. A luxury showroom called “the salon” is reserved for fixed-price sales. An equally lavish, retail-oriented space opened this year in Hong Kong.

….

On the financial side, Stewart and his team in 2021 revamped Sotheby’s Financial Services (SFS), a team of about 30 lending specialists who finance fine art and luxury goods, led by the former US head of lending solutions at J.P. Morgan Private Bank, Scott Milleisen. Sotheby’s has for years lent its own money to clients, with art as collateral, based on the house’s own assets, income, and capacity for debt, all of which have a natural ceiling. Milleisen introduced the client capital stack: after a loan is created, it’s pledged to capital providers in exchange for cash. According to Milleisen, for every $100 dollars of loans SFS produces, the providers give SFS somewhere between $85 and $95, which means that Sotheby’s is actually contributing somewhere between $5 and $15 dollars in cash. “It was an innovation that allowed us the ability to grow in an unconstrained way,” he told me. “It’s really only constrained by demand from clients.” Since Milleisen joined the house, he has roughly doubled Sotheby’s market share in the art lending business from $800 million to $1.6 billion. And there is room to grow. Milleisen says there is likely around $35 billion in art-secured loans globally, with new loan agreements signed every year.

—-

Of course, the Sotheby’s balance sheet isn’t all sunny. S&P Global Ratings downgraded Sotheby’s credit rating in June from B to B- after the company’s bonds fell 8 percent, and spooked investors who worry that refinancing loans due in 2026 won’t be possible. Late last year, Sotheby’s gave up plans for a possible IPO with a valuation of about $5 billion, excluding debt, with Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley as bankers. Around the same time, there were rumors that Sotheby’s was courting monied Europeans and the Qatar Investment Authority, hoping they would take on a minority stake in the company that would help boost capital. Those discussions faltered, but the rumors haven’t. Drahi is still interested, some say, in offloading around 30 percent of the house. “I don’t know where those rumors started, but I can tell you what we are interested in: growth and expansion,” Stewart told me. “People have asked, for example, if we are going public again. It’s not in our plans, but we are always interested in finding ways to grow. We’ve been good about partnering, and if there’s a time when it makes sense to consider growth capital because it adds to our growth plans, then we’ll consider it.”

—

Drahi, meanwhile, has a reputation as a cold-blooded cost-cutter, often at the expense of the specialists who drive the auction business. “Sotheby’s is losing, all day long, to Christie’s,” one art world insider told me, “even though they make more money. It’s because they are losing people.” In 2021 they lost rainmaker Amy Cappellazzo, who went on to become a founding partner at Art Intelligence Global. In May one of their most recognizable specialists of the post-Cappellazzo era, Brooke Lampley, left for a senior director position at Gagosian. “He doesn’t care about the experts or paying them what they’re worth,” the source said. However, Lisa Dennison, who joined Sotheby’s in 2007 after nearly 30 years at the Guggenheim, including a stint as museum director, reminded me that losing expertise is endemic in the auction world. “Charlie is the first person to come to senior leadership and say ‘who can we hire? Bring people to my attention.’ ”

—

In any event, auction house lifers told me, the secondary art market is a race to the bottom. “There’s a finite supply of good pictures out there,” one veteran of the field said. “To keep the business alive, you have to pull into categories where supplies are a little more endless: jewelry, cars, watches. You have to be diverse.” To this veteran, the battle isn’t with the other houses, it’s with the buyer, now a self-appointed expert. “People today like to think of themselves as experts. Why do they need Sotheby’s if they can research online and find a secondhand Patek Philippe or Hermès bag on their own? That’s what Charlie is really up against, and I don’t think he sees it. The brand is important, sure, but customers vote with their bank accounts.”

Whether Stewart’s plans bear fruit in the long run remains to be seen, but he doesn’t seem worried, least of all about the competition. At Café Sabarsky, his measured baritone cut through the lunch rush din. “Our path to success and to growth is not about us versus Christie’s,” he said. “There’s a little bit of a cultural obsession inside Sotheby’s, and in general, around how we are doing versus Christie’s. And there are good reasons for that. But I always say that talking about Sotheby’s and Christie’s is like talking about Oxford and Cambridge when debating global education. Sure, they’re interesting. However, it’s a big world out there. I think that having a very good competitor helps us challenge our thinking, stay at the top of our game, and keep on our toes. But frankly, I spend no time thinking about Christie’s. I hope they do really well.”

The Art Market Is Tanking. Sotheby’s Has Even Bigger Problems.

The auction house, owned by highly leveraged billionaire Patrick Drahi, is pushing off payments, awaiting a financial lifeline from an Abu Dhabi fund

By Kelly Crow, Matt Wirz and Ben Foldy

Sept. 24, 2024

The art market is grinding through a rough patch, and no one is feeling the pain more than Sotheby’s.

The sales downturn, driven in part by China’s economic slowdown, wars and volatile U.S. elections, has hit at a crunchtime for the auction house’s highly leveraged billionaire owner, Patrick Drahi, who is fighting fires amid restructuring in his broader telecom empire, Altice.

https://www.wsj.com/arts-culture/fine-art/art-market-sothebys-problems-6fa55009

Up-date 2024/10/1:

Hong Kong: the ups and downs of the art market

By Judith Benhamou Reports, 2024, 1. Nov

Quote:

The end of September is usually the time for major sales in Hong Kong, but at the last minute Sotheby’s announced they were going to postpone them to November 8 and 13 for reasons that seem unclear, justified by seeking to “reinvent the sales calendar to meet clients where they are.” This is a bad sign for the market, which could suggest that the company had not been able to source enough quality lots. Sotheby’s is also dedicating a large space to gallery activity in its new Hong Kong headquarters, run by Nathan Drahi, Patrick Drahi’s son, bringing together all kinds of objects from rare sneakers to antique furniture. The objective is to attract new collectors. The presentation of these precious objects would require to be further refined.

https://judithbenhamouhuet.com/hong-kong-the-ups-and-downs-of-the-art-market/

Up-date 2024/10/2:

ARTnews-letter, today:

The Headlines

SOTHEBY’S SPOOK. Concern about Sotheby’s financial woes, which are under recent media scrutiny, have risen to a new pitch. Reasons include a leaked report of fallen earnings in the first half of 2024 and a more recent Wall Street Journal article stating the auction house has been “pushing off payments” to art shippers and conservators, while reportedly struggling to pay its employees on time. However, Sotheby’s disputed the employee payment claims, and when questioned about rumors of more layoffs, informed Artnet News “no further redundancies were made since this summer.” Meanwhile, in today’s Puck newsletter, Wall Power , art market journalist Marion Maneker writes that the WSJ report about Sotheby’s money woes had “surprisingly little to back up the claim,” and has put “consignors, creditors, and employees … on high alert.” But “there’s some indication that at least one consignor got spooked” by recent news, and withdrew, Maneker notes. Meanwhile, all seem to acknowledge that the 280-year-old house is in major flux amid a host of challenges. Owned by Patrick Drahi , Sotheby’s has $1.8 billion of debt and is waiting for a $1 billion deal to close with an Abu Dhabi sovereign-wealth fund. Now, current and former Sotheby’s employees are concerned Drahi “has diminished this storied brand,” relays Maneker. But without Sotheby’s sending clear signs of reassurance to the market, Maneker concludes: “That silence – and the continued wait for Abu Dhabi to cut that check – has created a vacuum too easily filled with speculation and rumor mongering…”

2024/10/9 up-date

LUXURY

ART & CULTURE

OCTOBER 7, 2024

Bid for glory: The man bringing Sotheby’s into the 21st century

Former financier Charles Stewart, now CEO of the 280-year-old auction house, wants an even larger slice of the $65 billion art market. Will his grand plans pay off?

BY STEPHANIE BRIDGER-LINNING

quote:

My meeting with Stewart came just weeks before it was announced that ADQ, an Abu Dhabi sovereign wealth fund, had acquired a minority stake in Sotheby’s. In its reporting Reuters notes that Drahi had been ‘struggling with soaring debt costs because of a $60 billion debt pile that allowed him to build his media-to-telecoms empire in an era of low interest rates’. (The deal itself followed months of speculation – later denied – that Drahi wanted to take the business public.)

Together, ADQ and Drahi, who remains Sotheby’s majority shareholder, will invest approximately $1 billion and drive further expansion into the Middle East market.

Sotheby’s launched in the region with Sotheby’s Dubai in 2017, the same year the Louvre opened in Abu Dhabi, and has since more than tripled the number of permanent staff on the ground. They run a year-round programme of events in the Middle East and there could soon be more to come.

‘We haven’t closed the deal yet so we haven’t announced, and don’t have specific plans,’ says Stewart when we catch up on a call after news of the deal emerges. However, he does acknowledge the growing cultural might of the Middle East.

‘Middle Eastern collectors are already among the largest collectors across many categories – art, but also jewellery, watches and cars,’ he notes. The interest is reflected in the establishment of world-class museums which have ‘some of the most significant cultural agendas of any institution in the world. That’s true particularly in Abu Dhabi but also in Qatar and Saudi Arabia.’

https://spearswms.com/luxury/art-culture/sothebys-boss-charles-stewart-plans-auction-house-growth/

2024/12/12 up-date:

RUTHLESS CUTS AT SOTHEBY’S. Sotheby’s has swung the axe, severing 100 staffers from its New York offices. The victims are mostly back-office staff, junior employees, and specialists in various departments. The house attributed the cuts to this year’s challenging market conditions, emphasizing a focus on adapting its workforce to improve future performance and growth (buzzword: streamlining).

—–

Sotheby’s Lays Off 100 Staffers After Lower Results For Marquee Auctions in New York

December 11, 2024

Sotheby’s has cut 100 staff members from its offices in New York, with the majority of cuts including back-office works, junior staffers, and specialists in various departments, the auction house confirmed to ARTnews Wednesday.

In an email statement, a Sotheby’s spokesperson said, “Given the challenges the market has faced this year, we’ve taken a careful look at our business and staffing levels to perform well and grow going forward. We have an exceptionally talented team with outstanding expertise and capabilities across departments and around the world, and we are focused on delivering best-in-class services to our clients.”

Further staff cuts and closures at its international offices seem planned or already in process. When asked about the layoffs, a current employee at Sotheby’s London office responded to ARTnews that the situation is “wild.”

Artnet News, which first broke news of the layoffs Tuesday, reported that no official announcement was made by Sotheby’s internally. Puck’s Marion Maneker, who also reported on the cuts Tuesday, wrote that the layoffs included “business development roles to senior specialists in the impressionist and modern departments” as well as “antiquities, Americana, and Japanese art.” A Sotheby’s spokesperson disputed Maneker’s characterization of the redundancies, calling it “unsubstantiated.”

The come amidst an increasingly fragmented auction market. Sotheby’s recorded a much lower yield for Impressionist, modern and contemporary art at its November marquee sales in New York ($533.1 million) compared to 2023 ($1.2 billion).

Sotheby’s financial situation has been a source of concern for months after approximately 50 staff were cut at the auction house’s London offices in May. In September, a leaked report detailed an 88 percent decline in core earnings and a 25 percent drop in auction sales in the first half of 2024, followed by a Wall Street Journal report which said the auction house had been “pushing off payments” to art shippers and conservators.

In August, meanwhile, Sotheby’s announced an investment of nearly $1 billion from Abu Dhabi’s ADQ sovereign wealth fund; closing the deal in October. Prior to the deal with ADQ, Sotheby’s was solely owned by billionaire telecom magnate Patrick Drahi and had $1.8 billion in debt. As has been widely reported, Drahi’s companies currently have $60 billion in debt, with some loans requiring payment in 2027.

On November 1, Sotheby’s officially completed its purchase of the Breuer building on Madison Avenue in New York, the former home of the Whitney Museum of American Art, for $100 million. Documents from the New York City Department of Finance show the Breuer building was acquired by 945 Madison Avenue LLC through a $35 million mortgage from Barclays Bank and Sotheby’s signed a 15-year lease, set to expire on October 31, 2039.

Sotheby’s real estate holdings also grew this year with the opening of two international locations: a two-story, 24,000-square-foot maison in Hong Kong in July, as well as 10,800 square feet across five floors in Paris.

Puck also reported that staff reductions are taking place at Christie’s, “as often happens around this time of year, but not at the same scale.”

A Christie’s spokesperson refuted this, telling ARTnews, “Christie’s presently has no staffing changes of note planned. Like any business we continue to review our global resourcing needs to ensure we remain adaptable.”

https://www.artnews.com/art-news/market/sothebys-staff-layoffs-new-york-patrick-drahi-auctions

2024/12/14 up-date:

from:

https://www.instagram.com/p/DDM-vjPSmYh/?img_index=1

2024/12/18 up-date:

Fuller picture of Sotheby’s mass layoffs emerges

Staff cuts at auction house come as $1bn deal with Abu Dhabi wealth fund closes

16 December 2024

Almost two weeks ago, Sotheby’s senior staff were warned that another round of job cuts was about to happen. Since then, news of major staffing losses, first reported by Puck, has circulated—but only now is the full scale of the cost cutting becoming apparent.

While Sotheby’s says the number of people who have lost their jobs is more than 100, a source close to the matter says this is a conservative estimate. “It has been a slowly rolling process that began in September and has culminated in the last two weeks,” they say. Several staff are understood to be moving into reduced advisory roles.

“Given the challenges the market has faced this year, we’ve taken a careful look at our business and staffing levels to perform well and grow going forward,” a spokesperson for Sotheby’s says.

The redundancies, which come after an earlier round of approximately 50 job cuts in London in May, are due to be pushed through by the end of 2024 and have mainly affected staff in the US, but also those in London, Europe and Asia. The source says Sotheby’s is attempting to slash $100m from the budget; the auction house denies this and declined to give a figure for the amount it is aiming to cut.

Departments most at risk

Bigger departments including Impressionist, Modern and contemporary art, have sustained “significant losses, in the form of senior roles”, according to the source. Large numbers of more junior personnel have also been affected. Regional offices have been closed across the world, including in Bangkok and a number of offices in Europe. “It’s really across the board in terms of people cuts, as well as significant budget reductions,” the source says.

Some smaller departments are understood to be at risk of closure, including Antiquities, Americana, Japanese and some areas of decorative arts. A spokesperson for Sotheby’s says: “Discussions are currently ongoing with these departments and none of them have been shut down.” The firm declined to comment on whether these departments would continue to operate after their next sales in the coming months.

The cuts come as Sotheby’s $1bn deal with the Abu Dhabi–based sovereign wealth fund ADQ was closed in November. A large chunk of that investment has been used to pay off some of the $1.65bn of fixed debt tied to Sotheby’s auction business. The French-Israeli telecoms tycoon Patrick Drahi acquired Sotheby’s for $3.7bn in 2019, bringing his company Altice’s debt totals to around $60bn.

The Art Newspaper understands that a cost reduction was promised as part of Sotheby’s deal with Abu Dhabi, where the auction house’s chief executive Charles F. Stewart was visiting on business when news of the job losses broke earlier this week. Stewart removed a number of comments under an Instagram post of his Abu Dhabi trip after several people questioned his absence in New York and handling of the matter.

Unlike in 2014, when the last round of major cuts was made at Sotheby’s, sources say there has been very little transparency or communication from senior management about the current process, with some accidentally finding out they have lost their jobs via condolence text messages from colleagues. The source with insider knowledge says: “It feels like there is no strategy. The company is in a state of freefall.” The Sotheby’s spokesperson says the decisions “have not been taken lightly and we are committed to ensuring a smooth transition for our employees”.

While a mandate to make the auction business leaner has driven some of the cuts over the summer and autumn, the source says the recent cuts “are focused on trying to reach lofty financial targets that are being set”.

They come at the end of another tough year for the market. In July, figures from London-based analysts ArtTactic showed that worldwide sales at Sotheby’s, Christie’s and Phillips slumped 27% in the first half of 2024. New York’s marquee sales last month were down an estimated 50% on the year before; the trade is now braced for the end of year results which are expected this week.

However, Sotheby’s issues appear larger than the current downward cycle in the market.

Within weeks of purchasing Sotheby’s in 2019, Drahi established a new company to complete a sale-and-leaseback transaction, releasing equity in the firm’s Bond Street headquarters in London, which was passed up a chain of companies. It is a model Drahi has also employed in New York and elsewhere. “All of the traditional real estate that Sotheby’s owns, whether it be Bond Street or York Avenue, has been completely stripped,” says the source.

According to the latest accounts filed on Companies House in December 2023, profits after tax for the UK arm of the company were just over £22m, while a £41m dividend was paid out. The Sotheby’s spokesperson says it is “a myth” that Drahi has taken any dividends out of Sotheby’s. “In fact, the opposite is true,” they say. “Mr Drahi has invested additional capital into the company without removing any of his investment.”

Introducing the new fee structure last year, which reduced buyers’ premium in favour of shifting more costs onto sellers, only amplified problems, insiders say. “Shifting the fees to consignors has made it incredibly hard to get business,” says one. “In order to get people in the door to buy you need property and you need the supply. If you’re cutting off your supply, you’re not going to have the demand.” The Sotheby’s spokesperson says that supply “has been a challenge across the industry […] but we are honoured to have offered many of the greatest collections across the industry this year”.

While insiders say it appears that the bottom has been reached with this latest round of job cuts, it is not clear how long that will last. As the source says: “I think people are now just looking for some normalcy, but it’s a pretty sad future.”

https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2024/12/16/fuller-picture-of-mass-sothebys-layoffs-emerges

2024/12/21 up-date:

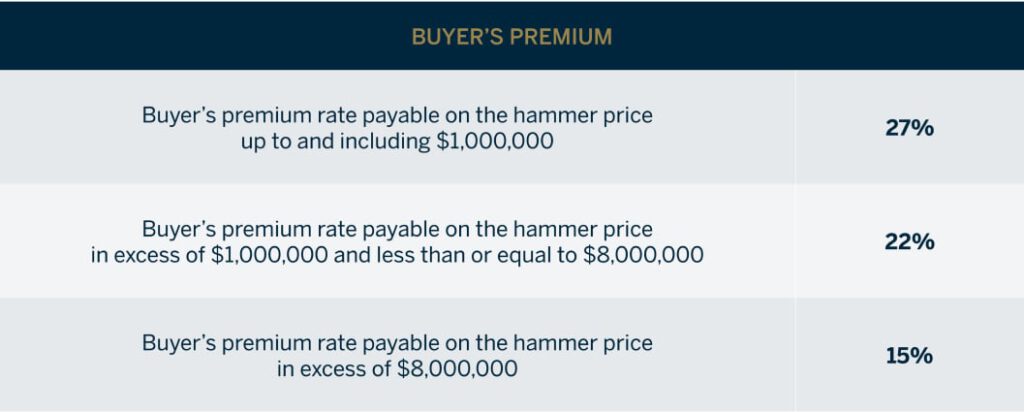

SOTHEBY’S BACKTRACKS. Sotheby’s has reversed course on its new fee structure, which had once been hailed as a “smart disruption” and a sign of the art market’s growing “maturity,” per CEO Charles Stewart, As Harrison Jacobs reported for ARTnews Thursday, the new terms drew complaints from clients, according to the auction house, which has seen a drop in sales this year and has been laying off staff. In a letter sent yesterday, Sotheby’s said it was returning to its “bespoke” fee terms for sellers, and the buyer’s premium will range from 15 percent to 27 percent of the hammer price. After “evaluating the needs and preferences of both our buyers and sellers,” the company conceded the fee terms weren’t delivering. “We need to be responsive. We’ve tried, we’ve learnt and we’ve listened,” Stewart told the Art Newspaper.

Our Fee Structure

Dear Clients,

You may recall that, earlier this year, we announced a bold initiative to reduce our Buyer’s Premium to a flat 20% on almost everything we sell, and to create fixed financial terms for sellers bringing their material to auction. The idea was to encourage growth in our markets by creating transparency, simplicity, and fairness on fees that have always been intimidatingly complex.

Over the past 6 months we have listened to the market, evaluating the needs and preferences of both our buyers and sellers. So starting February 17, we will reintroduce bespoke terms for sellers while maintaining the underlying principles that motivated this change. Our Buyer’s Premium will be as follows.

This updated Buyer’s Premium will apply to all categories excluding wine & spirits, automobiles, and real estate. Terms will be posted to our website when they take effect and will include information about additional currencies.

We look forward to working with you in the new year.

2025/6/26 up-date:

Hong Kong Developer Sought Loans Backed by Picasso, Warhol Art

Summary

The Parkview Group, a prominent Hong Kong property dynasty, sought a loan from Sotheby’s backed by over 200 artworks from renowned artists like Andy Warhol and Pablo Picasso.

Bloomberg, June 25, 2025

Picasso’s “Femme tenant un chat dans ses Bras”Photographer: Odd Andersen/AFP/Getty Images

A Hong Kong property dynasty that became one of the city’s most prolific collectors is discovering the limits of the burgeoning world of art-backed lending.

The family behind Parkview Group, which narrowly avoided a default in March, sought a loan earlier this year from international auction house Sotheby’s, people familiar with the matter said. It was to be backed by more than 200 artworks, from the likes of Andy Warhol, Pablo Picasso, Salvador Dali and Chinese artists such as Yue Minjun, Qi Baishi and Zao Wou-ki, according to the people.

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2025-06-24/hong-kong-developer-sought-loans-backed-by-picasso-warhol-art

…

Hong Kong-Taiwan Parkview Group (Chyau Fwu Properties) Hwang family is reported to have attempted art financing using art pieces including Picasso & Vincent Van Gogh with auction house Sotheby’s in early 2025. Parkview Group is also reported to have avoided loan default. Parkview Group listed company in Hong Kong is Joy City Property (Previously The Hong Kong Parkview Group) with $475 million market value. Joy City Property parent is COFCO Land which acquired Hong Kong Parkview Group in 2012. Joy City Property – Joy City Property is owned and managed by its parent company, COFCO Corporation. As the overseas listed platform of COFCO Corporation, it is primarily engaged in the development, operation, sales, lease and management of mixed-use complexes portfolio under the flagship brand “Joy City (大悅城)”. As at 4 December 2014, Joy City Property owns a total of 18 commercial property projects, including eight mixed-use complex projects, four commercial property projects, four hotel projects, one integrated tourist project and one project with minority interest. The Parkview Group – The Parkview Group is a conglomerate of private companies. Parkview’s roots lie in the Chyau Fwu Group, a pioneering construction and development business founded in Taiwan in the 1950s. Principally focused on major infrastructure projects, Chyau Fwu was a key player at the vanguard of Taiwan’s early development. As the company moved into property investment and development, it cemented a reputation for top-end landmark projects that set new benchmarks for quality and innovation. Built by Chyau Fwu in 1960s, Bank Tower in Taipei, was the South East Asia’s first green building with energy saving glass finishes. One of its recent projects, 200,000 sqm Parkview Green in Beijing, was the first mixed use development in China to be awarded the LEED Platinum Certification (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) in 2009 and Asia’s first LEED Dynamic Plaque in 2017. The Parkview Group of today has diverse investments in Europe and Asia ranging from the top-end residential and hotel developments, cutting edge construction and materials research facilities to arts organisations.

Up-date 2025/8/21

Sotheby’s Institute of Art Under Federal Sanction Amid Questions About Financial Stability

August 20, 2025

Sotheby’s Institute of Art, a for-profit graduate school with campuses in London and New York, has been under one of the US Department of Education’s most serious financial sanctions for nearly two years, according to previously unreported public records.

Since December 2023, the school has been given the “Heightened Cash Monitoring 2” (HCM2) designation, which is used by the DOE when it identifies significant concerns with a school’s finances or compliance practices. Fewer than 50 schools in the country currently hold the status, most of them small religious or cosmetology schools. Under HCM2, a school is barred from receiving federal financial aid in advance and must instead front its own funds and apply for reimbursement. The designation is meant as a warning to prospective and current students that an institution may be at risk of closure.

SIA was founded by the eponymous auction house in 1969 to train students in the business of art. It offers master’s degrees and certificate programs, with many graduates going on to work at auction houses or other market-oriented companies, or independently as art advisers. Since 2005, however, the school has been owned by the Maryland-based investment firm Cambridge Information Group (CIG) and has retained the Sotheby’s name through a licensing agreement. It is currently operated by BrandEd, a subsidiary of CIG, and has been accredited to confer degrees in New York since 2016. It does so in London through a partnership with the University of Manchester.

….

Also in the filing, the company’s financial statements showed difficulty raising profitability and reducing its accumulated losses. In 2019, SIA generated £8.1 million in revenue and had £8.3 million in costs. While income grew to £9 million in 2023, costs rose alongside it to £9.35 million. That same year, the school reported £4.7 million in accumulated losses—a figure dating to investments made by CIG as it took over SIA in 2005. As of its most recent financial statement, for fiscal year 2024, accumulated losses had been reduced modestly to £4.36 million.

…

Joanne Kesten, an art adviser and appraiser who has taught courses at SIA and NYU, told ARTnews that demand for professional degrees focused on the art market has been driven more by perceived value than actual value. She added that the decline of programs like SIA’s had become increasingly apparent in the 2010s. In 2014, NYU discontinued its appraisal certificate program; in 2020, Christie’s Education ended its masters degree programs after 42 years, and now only offers online-only or short in-person courses.

full text:

https://www.artnews.com/art-news/market/sothebys-institute-of-art-under-federal-financial-sanctions-1234749624

2025/8/26 up-date:

Sotheby’s Employees Likened Patrick Drahi’s Rule at the Auction House to Trump

August 25, 2025

quotes:

In the New Yorker piece, Knight spoke with dozens of current and former Sotheby’s employees, who said that the fee debacle were the nadir of Drahi’s ownership, likening it to Trump’s obsession with tariffs and trade disputes.

“It has huge parallels to the way Trump rules in the United States. It’s that kind of chaos that is totally not necessary,” a former executive told the New Yorker. “It’s, like, why did you do that?”

One Sotheby’s employee went so far as to describe the six months of the new fee structure—when Sotheby’s profits plummeted—as “Shakespearean.”

Knight further reports that the house’s chairmen lobbied Drahi directly in June 2024 to reverse the new fees, with Grégoire Billaut, chairman of contemporary art, reportedly telling Drahi, “You need to do something.” Billaut went on, “I’m losing business. I never lose. And now I’m losing and I can’t take it anymore.”

Drahi, in Knight’s telling, was furious, telling Billaut, “If that is how you feel, then walk out the door … This is not a democracy. It’s my company, and I run this company. At the end of the day, all of you, every single one of you, is replaceable.”

full text:

https://www.artnews.com/art-news/market/sothebys-fee-structure-trump-tariffs-1234749865

2025/8/28 up-date:

How a Billionaire Owner Brought Turmoil and Trouble to Sotheby’s

Patrick Drahi made a fortune through debt-fuelled telecommunications companies. Now he’s bringing his methods to the art market.

August 25, 2025

When Patrick Drahi, a fifty-five-year-old French Israeli telecommunications billionaire, agreed to buy Sotheby’s, one of the world’s two great auction houses, early in the summer of 2019, people in the art market had two questions: Who is Drahi? And what does he want?

On a superficial level, buying an auction house is the kind of thing that French billionaires do. Christie’s, a rival of Sotheby’s since the seventeen-sixties, has been owned by François Pinault, a French luxury-goods magnate and prolific art collector, for the past quarter century. A former banker who worked with Drahi described the acquisition to me as an heirloom. “Think about your obituary,” he said. “Are you likely to be recalled for having done many cable deals, or having owned Sotheby’s?”

But Drahi, who had a net worth of around eight billion dollars, seemed to come out of nowhere. Although a spokesperson described him as a connoisseur with “an encyclopaedic knowledge of classical music and paintings particularly,” he wasn’t considered a major player in the art market. Artprice, a French art-sales database, reportedly listed Drahi as the two-hundred-and-fifty-second-biggest art collector in the world.

Moreover, unlike Pinault and Bernard Arnault, another French luxury-goods billionaire, who used to own Phillips (an auction house that, like Sotheby’s and Christie’s, was founded in London in the eighteenth century), Drahi did not seem eager for a public profile. Whereas Pinault and Arnault were household names in France and had major foundations, Drahi was more elusive, dividing his time among Switzerland, Israel, and the Caribbean island of Nevis. “He is not in Paris. He is not in New York. He is not in London,” a person close to Drahi said. “He is not where his counterparts are. He is not spending a single minute in any cocktail or public event.”

Sotheby’s was also unlike any other company that Drahi had ever owned. Between them, Sotheby’s and Christie’s conduct about twenty per cent of global art sales—ten to fifteen billion dollars a year—but they are, in many ways, esoteric organizations. Employees, dealers, and art advisers liken the duopoly to a pair of medieval guilds, or sports teams, or theatre companies, doomed and inspired in equal measure by a state of permanent competition. “People feel such a connection to the company,” one longtime Sotheby’s employee, who recently left the auction house, said. “For many of them, it’s just so much of their whole lives. And putting together an auction, it’s like putting on the big school play.”

Until then, Drahi had done business almost exclusively in the telecommunications sector. He was the founder and main shareholder of Altice, an international cable, TV, broadband, and mobile-phone provider that was named for a sacred grove in ancient Greece. He had a reputation as a formidable dealmaker with uncanny confidence in his own judgment. “He doesn’t think outside the box,” the Drahi associate said. “He thinks there is no box.” A former telecom banker who worked on several transactions involving Drahi in the early two-thousands chose three adjectives to describe him: “One, smart. Two, aggressive. Three, utterly unsentimental.”

Drahi has been referred to as a wizard of debt. “He has built, since Day One, all of his companies with debt,” the associate said. His appetite for risk meant that Altice’s fortunes, and his own, could dramatically fluctuate. But he seemed to thrive, rather than wilt, during such situations. “He likes it. He likes it,” the associate said, as if to emphasize Drahi’s unusual fortitude. The first banker told me, “Very rarely do you find people that are able to master the numbers but also the brinkmanship,” adding, “You could say, ‘Well, what for?’ But, you know, that’s a Nietzschean question.”

The Drahi takeover valued Sotheby’s at $3.7 billion. Employees got their first glimpse of the new owner at an all-staff town hall at the company’s New York headquarters, on York Avenue, in early October, 2019, on the day that the deal was finalized. The meeting took place in the main salesroom, on the seventh floor, and consisted of a question-and-answer session with Tad Smith, the company’s chief executive. Smith, a former C.E.O. of Madison Square Garden, was an assiduous, somewhat robotic character, who had been appointed four and a half years earlier to modernize the auction house, which was the oldest company listed on the New York Stock Exchange.

For years, it had been axiomatic among Sotheby’s employees that the auction house would benefit from having a single, rich proprietor, as Christie’s did. “Looking back, I realized Tad was brought in to sell the company,” a former senior executive told me. The last private owner of Sotheby’s was Alfred Taubman, a charismatic Midwestern mall developer, who bought the auction house in the early eighties and helped to transform it into a glamorous retail experience. (Taubman was later convicted of colluding with Christie’s to fix pricing and spent ten months in prison, but he is still fondly remembered at Sotheby’s as a pioneer of the modern art market.)

In person, however, Drahi did not make a big impression. “He was not an Alfred Taubman. He’s not a larger-than-life person. He’s just the opposite,” the longtime Sotheby’s employee said. “I found him a little geeky.” Drahi emphasized that he was buying the auction house for his family. (Within days of the deal going through, all four of his children were given Sotheby’s e-mail addresses.) He stressed his admiration for the Sotheby’s brand, but he also warned that the company would be run differently from now on. “I make quick decisions,” another former executive recalled him saying. “Most of the time, they’re right—sometimes they’re wrong. And if they’re wrong we fix them. But I don’t like getting stuck in the past.”

“I don’t think anyone was terrified, but they certainly weren’t reassured,” the former executive said. Drahi’s previous acquisitions were associated with brutal restructurings and, often, declining levels of service. In the French media, Drahi was caricatured as a “cost killer.” Soon after Altice bought the New York-based cable company Cablevision, he told a conference, “I don’t like to pay salaries. I pay as little as I can.” In 2017, Drahi gave a speech that was broadcast to employees around the world. “If you want the comfort and stability of a large bureaucracy,” he said, “Altice is not for you.”

In early, private meetings with Sotheby’s senior staff, Drahi came across as highly intelligent but also caustically blunt. “He just says whatever he’s thinking,” the former senior executive said. Another recalled, “He walked in like he knew the business and what he needed to do.” A third described their meeting as perplexing: “He kind of philosophized, and then asked a couple questions that seemed really out of left field.” A fourth executive warned Drahi that he would face resistance if he tried to change the company too fast. “He said, ‘That’s fine,’ ” the executive recalled. “ ‘I don’t mind breaking things.’ ” Drahi confided that he thought that the auction house employed too many people and that its senior staff were overpaid. But when he was asked at the town hall whether he was planning any layoffs, he said that he didn’t think so. “All I was thinking was, Wow,” a fifth executive said. “They are poring over the company right now, looking for cost reductions.”