リチャード・プリンス と著作権の問題:「元ソニック・ユースのキム・ゴードン」作 @ Blum & Poe 東京 Richard Prince and copyright issues: 'ex Sonic Youth Kim Gordon' @ Blum & Poe, Tokyo

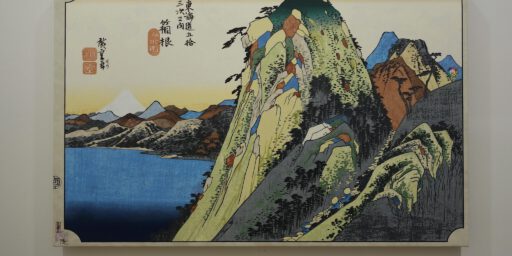

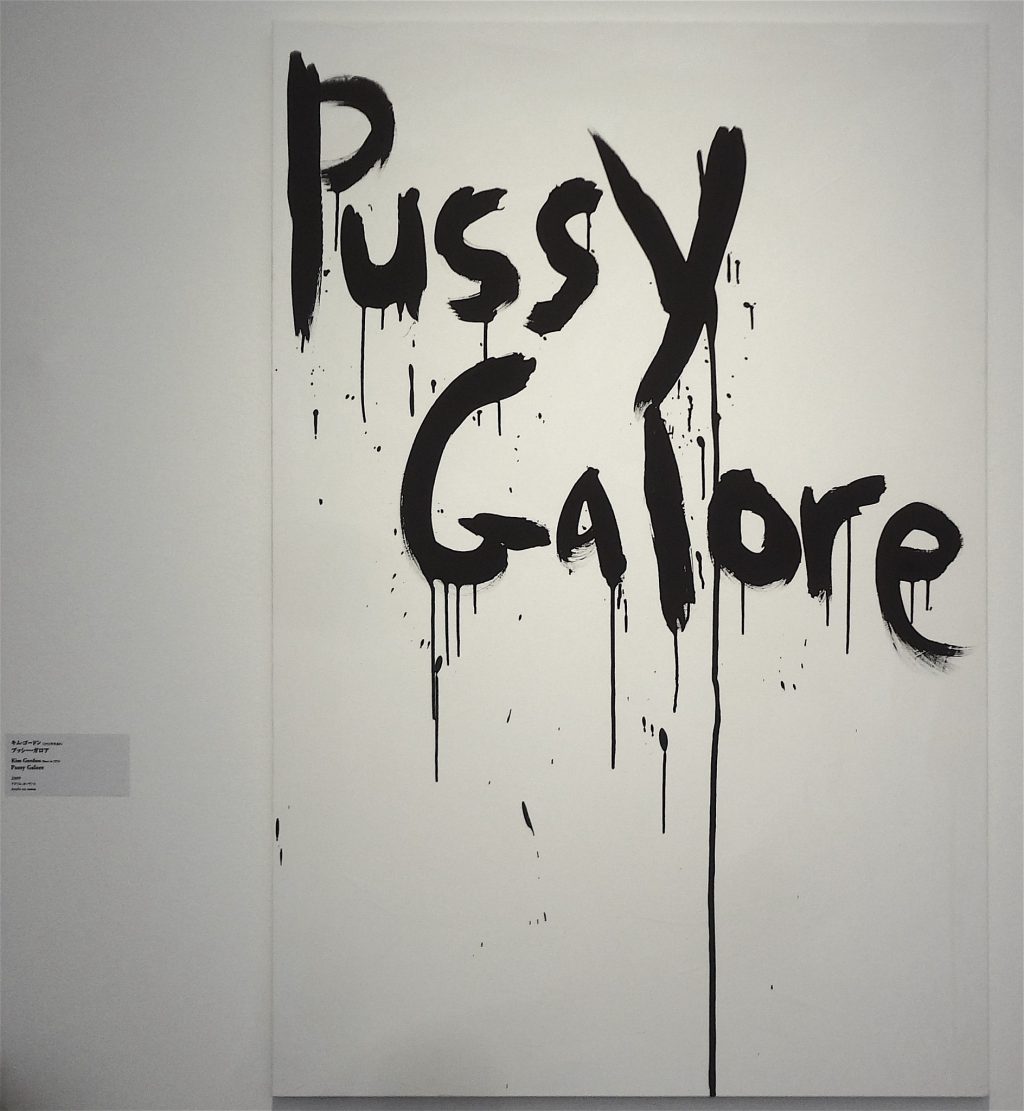

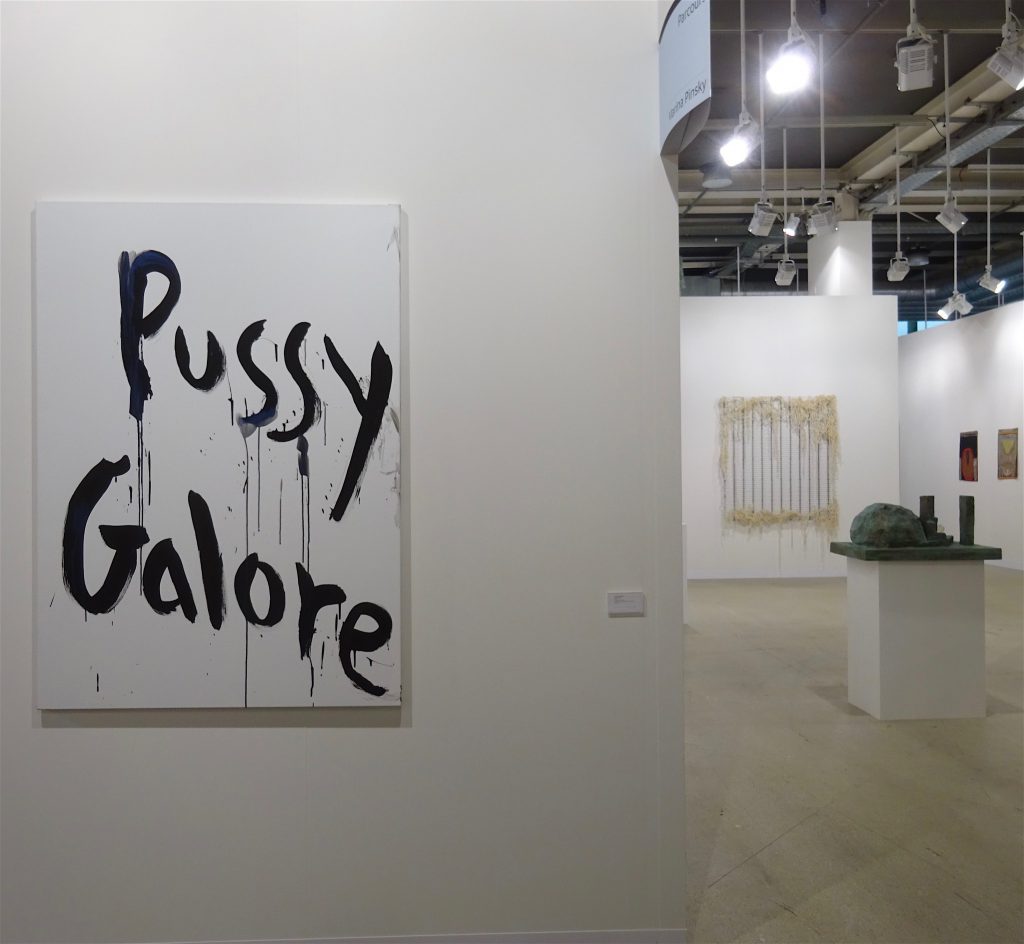

1 hour ago, The Art Newspaper reported that Richard Prince is defending the reuse of others’ photographs. One of the two photographs in question is the above picture, which I took at the gallery Blum & Poe, Tokyo in 2015.

As myself experienced many times in my artistic career, that my pictures had been re-used with slight modification or just re-appropriated, I know how it feels as the original creator. However, in this regard, I’m relaxed and don’t mind. Art itself is always in motion, copyright infringements in the age of the internet and digital data should not be seen in a narrow view. A ‘common sense’-attitude via the re-use of pics should be applied, iPhone snapshots with high resolution rule the world now. Almost every museum allows to take pictures.

In the case of Richard Prince vs. Eric McNatt we’ll follow the next steps.

最近、キュレーター達の間で話題になっている「curatorial ethics」や、アーティストの名声の追求は、「関係性の美学」に対して、疑問が見えつつあります。 何十年も、プリンスはアートの独創性を再コンテキストし、原作者や原所有者といった 社会理念を覆させ、アート作品の視点を変えて考えさせる事をテーマにしていました。 そしてついに、新作品群を巡る「インスタグラム・オン・キャンバス」(一枚= 約 100.000 US$ / 約1200万円)では、最先端なウォーホル風の、マネー・プリンターの過程をたどっています。

この作品は、アーティスト実践における疑念を抱かざるを得ない「when art is over」 と解釈できます。 しかしある意味、sardonic perspective趣味における、作家自身とオーディエンス(=インスタグラム・ユーザー)の物語体を読み取ることもできます。 ポスト・関係性の美学の概念を巡って、相互に関係のあるフェイスブックやツイッタ ー、インスタグラム、ユーチューブは、アーティスト達の発表媒体として利用され、正に、プリンスが現代アート実践の行き詰まった状態を崇高な精神で見せていると言える でしょう。

Richard Prince defends reuse of others’ photographs

In court motions, he argues that his appropriation explores the virtual world of social media

The Art Newspaper, LAURA GILBERT, 10th October 2018

quote:

“Prince argues that he had to use as much of the photograph as appeared in the Instagram post to accomplish his purpose. In a 15-page statement calling his iPhone a paintbrush, Prince explains that he wanted “to reimagine traditional portraiture and bring to a canvas and art gallery a physical representation of the virtual world of social media”. Had he altered the photographs, he says, that intent would go unseen.”

up-date, see also:

リチャード・プリンス @ Gagosian Beverly Hills 2020

Richard Prince @ Gagosian Beverly Hills 2020

https://art-culture.world/articles/リチャード・プリンス-gagosian-beverly-hills-2020/

Sonic Youth – I Wanna Be Your Dog (1989)

アップデート:

“I never really thought of myself as a musician. I’m not saying Sonic Youth was a conceptual-art project for me, but in a way, it was an extension of Warhol. Instead of making criticism about popular culture, as a lot of artists do, I worked within it to do something.”

— Kim Gordon via Elle.com

up-date 2018/10/17

Lynn Goldsmith against Andy Warhol

Fair use or foul? An appropriation case involving Warhol raises an artistic debate in New York court

A legal battle over the Pop artist’s portraits of Prince is heating up

The Art Newspaper, LAURA GILBERT

15th October 2018

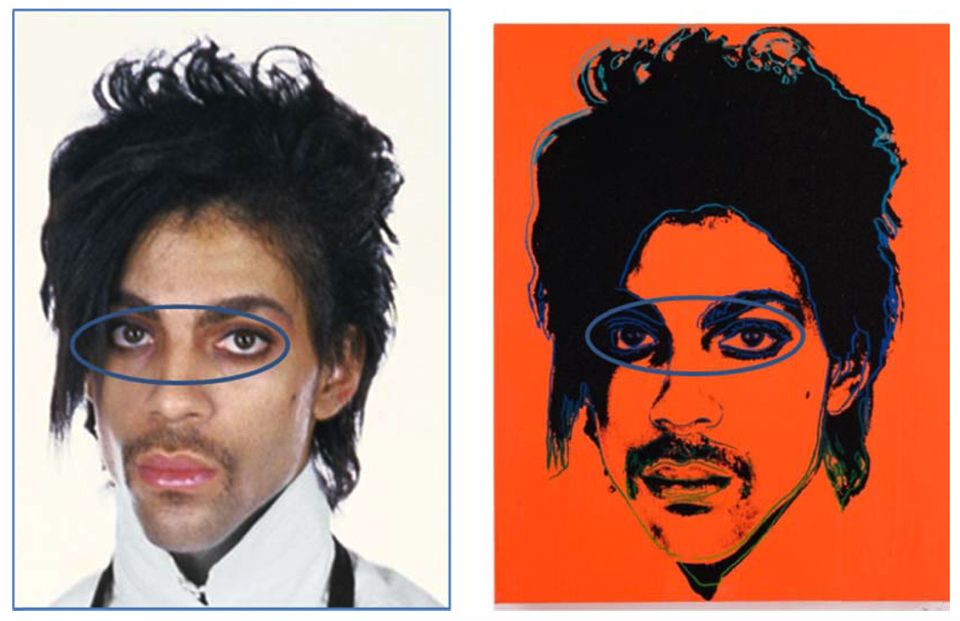

When is appropriation fair use and when is it foul? In a heated lawsuit, the Andy Warhol Foundation is asking a Manhattan federal court to “stay on the right side of history” and “reject” what it calls a photographer’s “effort to trample on the First Amendment and stifle artistic creativity”. For her part, Lynn Goldsmith, a celebrity and fine-art photographer, warns that a ruling in the Foundation’s favour “would give a free pass to appropriation artists” and destroy licensing markets for commercial photographers. Both combatants’ made their pleas in cross-motions for summary judgment filed Friday (12 October).

In 1984, Goldsmith granted Vanity Fair a one-time license to use her photograph of pop musician Prince as source material for an artist’s illustration. The artist was Warhol, who created not just the illustration for Vanity Fair but 15 other portraits of Prince. In 2016, the Foundation licensed one of those portraits to Condé Nast for $10,000 for the cover of a magazine devoted to Prince published shortly after the musician’s death. The portraits have been exhibited in museums, 12 were sold, and four are in the Andy Warhol Museum. Goldsmith says she learned of Warhol’s series from online images posted after Prince died.

The one licensed use she granted Vanity Fair “did not give Warhol free reign to then create 15 other versions” or the Foundation the right to license all 16, Goldsmith says. She contends the Foundation violated her exclusive rights under copyright law to reproduce, display, license and distribute works derived from her photograph.

The Foundation first questions whether Warhol used Goldsmith’s image. “There is no evidence that he was given the photograph”, its papers say, but “somehow” he created the works. In any event, the Foundation continues, Warhol’s images fall under fair use in copyright law because they have a different aesthetic and meaning and do not usurp Goldsmith’s market. In cropping and flattening the image, he made it “disembodied and mask-like”. Whereas the photograph depicts Prince the person, Warhol’s Prince is an “icon or totem” commenting on celebrity and “defining the contemporary conditions of life”, the Foundation argues.

Warhol’s works do not compete with Goldsmith’s market, the Foundation contends: Warhols sell through high-end galleries and auction houses to wealthy buyers, Goldsmith through photography galleries targeting buyers interested in photographs of musicians.

According to Goldsmith, though, the aesthetic changes in Warhol’s images are “relatively minimal” and the series retains her photograph’s essence, composition, and such elements as Prince’s intense stare and the sheen from the lip gloss she applied. And, she argues, their licensing markets for commercial uses, including magazines, overlap. Her works are also in museums, and one wealthy collector owns one of her Prince photographs as well as Warhol’s works, she notes.

Goldsmith says the singular expression of Prince in her photograph “cannot be replicated by any other photo of Prince, but it can be substituted by the Warhol images that reflect the essence of that photo”. But to the Foundation, the lawsuit is really about “Andy Warhol’s legacy and protecting his transformative and innovative artistic works”.

https://www.theartnewspaper.com/news/fair-use-or-foul-an-appropriation-case-involving-warhol-raises-an-artistic-debate-in-new-york-court

up-date 2019/7/3:

Warhol’s works are protected by fair use because they are “transformative” of the original photo and “add something new to the world of art”

https://art-culture.world/articles/andy-warhol-prints/

up-date 2019/10/1:

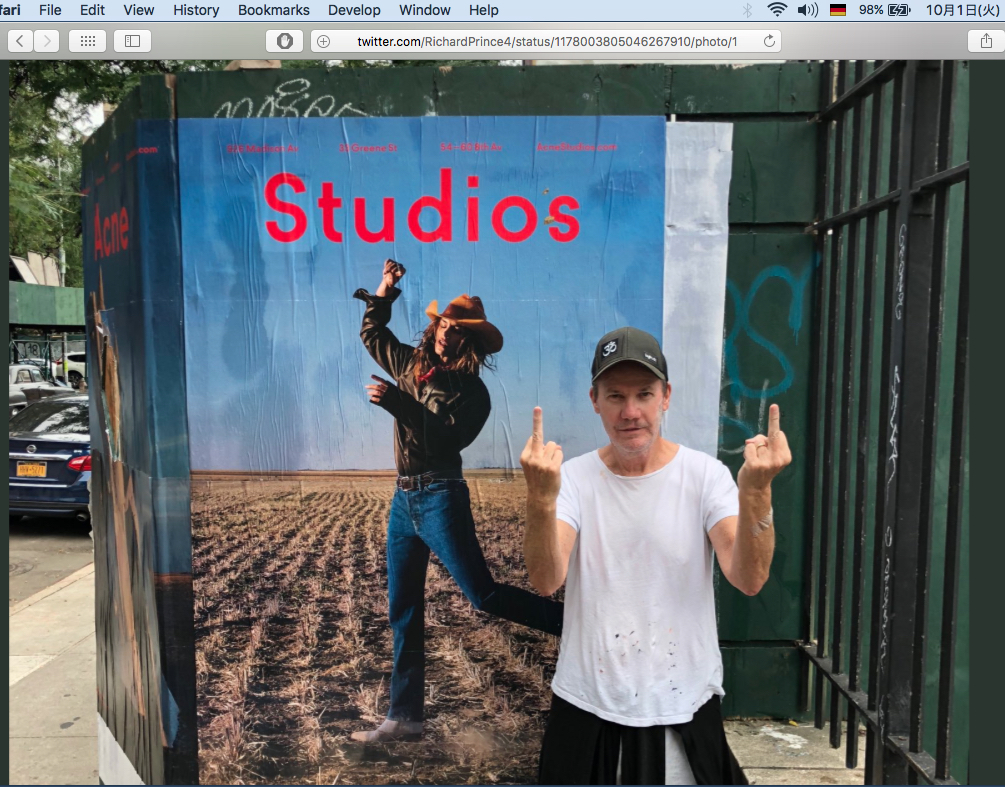

https://twitter.com/RichardPrince4/status/1178003805046267910

Richard Prince

@RichardPrince4

So I’m walking in the East Village the other day and I see one of my cowgirl photos used by another photographer. I guess I had it comin. Take my art, please. (This of course is total bullshit)

——

up-date 2020/7/30

Proof Is in the Pixels for Appropriation Artist Richard Prince

July 28, 2020, JOSH RUSSELL

MANHATTAN (CN) — Fighting copyright claims over Richard Prince’s “New Portraits” series consisting of other people’s Instagram posts, lawyers for the controversial appropriation artist argued in court Tuesday that size matters.

The federal case pitting Prince against photographers Donald Graham and Eric McNatt has been brewing for years, getting underway this afternoon in a Skype videoconference — as has become typical for court proceedings during the coronavirus pandemic.

“Most people, when you’re looking at Instagram, you look at it on a phone, on a very small screen,” Prince’s attorney Ian Ballon told U.S. District Judge Sidney Stein. “It’s called ‘New Portraits’ because it shows the difference with traditional portraiture.

“And what Prince has done is he’s blown up to absurd proportion — up to 40 times larger than the way that people look at social media — and put them in an art gallery. And it’s a way to confront the new portraiture.”

Prince exhibited “Portrait of Rastajay92,” a blown-up Graham print of a Rastafarian smoking a joint, at New York’s Gagosian Gallery in fall 2014. During that same period, Prince’s own Instagram account included McNatt’s photograph of musician-artist Kim Gordon, with no credit to McNatt or to Paper Magazine, which had published the image for its 30th Anniversary issue that July.

Besides blowing them up in size, Prince’s only modifications to the images were in comments underneath the pictures comprised of emojis and eccentric captions.

At Tuesday’s hearing, McNatt’s attorney called Prince’s so-called contributions nothing more than “gobbledygook nonsensical comments.”

“Notwithstanding these additions, plaintiff’s unobstructed, unaltered photographs are the dominant images in the two Prince works,” said Caitlin Fitzpatrick, with the firm Cravath, Swaine & Moore.

Prince’s lawyer cast the images meanwhile as commentary on the narcissism of modern social media, saying the series forces the audience to confront the modern culture surrounding Instagram in a way that neither original does.

“Traditional portraiture, of which these two original photographs are, involves someone taking a staged photo,” said Ballon, who is with the firm Greenberg Traurig. “Instagram and social media involve selfie culture. It’s a certain kind of pop culture and narcissism.

“More importantly, it has a different purpose and a different meaning. Prince’s purpose was to comment on social media, to satirize how people communicate today.”

Arguing that Prince’s works are transformative and thus protected under the fair-use provisions of copyright law, Prince has moved for summary judgment in both the Graham and McNatt cases.

Fitzpatrick told the court Tuesday, however, that Prince’s own deposition testimony belie his argument that the commentary is transformative.

“I wanted to have fun, I wanted to make people feel good, I wanted to make art,” Fitzpatrick said, reciting the artist’s explanation of his intent for the works.

In Prince’s post “Portrait of Kim Gordon,” he added in the comments: “Kool Thang You Make My Heart Sang You Make Everythang Groovy” — a sort of portmanteau referencing the 1960s garage-rock hit “Wild Thing,” made popular by the Troggs, and Gordon’s own song “Kool Thing” from Sonic Youth’s 1990 major label debut album “Goo.”

Ballon asserted that Prince’s allusions in the comments to pop songs, and his friendship with Gordon, are typical of social-media culture on Instagram. “It’s all self-referential, it’s all about pop culture,” he said.

Gordon’s long-running downtown Manhattan art-rock band Sonic Youth often used modern artists’ work for the group’s album covers, taking a painting from Prince’s nurse series for its 2004 album, “Sonic Nurse.” Gordon, who is also a visual artist, painted the cover for Richard Prince’s 2016 record, “Long Song.”

Ballon also argued that Prince’s works should be protected because they do not harm the market for Graham or McNatt’s output — another factor in fair use.

“There is no question that these are not substitutes,” he said Tuesday. “The price points are completely different. The sales channels are different, they’re marketed in different places.”

Judge Stein concluded the hearing after nearly 90 minutes, reserving judgment.

Prince has been exhibiting his “New Portraits” collection for the last six years. A recent staging at the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit drew backlash from new portrait subjects like Zoë Ligon, an online influencer who owns a sex-toy shop in Detroit.

“Imagine my surprise when I saw Richard Prince tweet a 6ft inkjet printed picture of a screenshot of an Instagram post of mine hanging up in my hometown of Detroit at MOCAD,” Ligon wrote in a November 2019 post to her 287,000 Instagram followers. “I didn’t consent to my face hanging in this art gallery.

“What Richard is doing is questionably legal, but even if something is legal and ‘starts a dialogue’ it doesn’t mean you should actually do it. Not all legal things are ethical. This, in my opinion, is a reckless, embarrassing, and uninformed critique of social media and public domain.”

https://www.courthousenews.com/proof-is-in-the-pixels-for-appropriation-artist-richard-prince/

Another case 2022/7/8

French Court Tosses Out Sculptor’s Lawsuit Over Authorship of Maurizio Cattelan Works

July 8, 2022

A French judge has dismissed a lawsuit over whether Maurizio Cattelan could be considered the true author of some of his most famous sculptures.

Sculptor Daniel Druet had sued Cattelan’s gallery, Perrotin, and the Monnaie de Paris, the art space that mounted a Cattelan show in 2016. Druet claimed that he was the true maker of nine of Cattelan’s works, among them Him, a famed 2001 sculpture of a kneeling Adolf Hitler.

The Paris court that issued the decision said that Druet, a maker of wax effigies, was effectively working for hire when Cattelan asked him to help produce the works and was therefore not the author of these objects.

The judgement reads, in part, “Daniel Druet was in no position – nor did he seek to do so – to take the slightest part in the choices relating to the scenic setting of the said effigies (choice of building and size of the rooms housing a given character, direction of the gaze, lighting, even the destruction of a glass roof or the parquet floor to make the staging more realistic and striking) or the content of the possible message to be conveyed through this staging.”

Druet and Emmanuel Perrotin, the founder of the Paris-based gallery that represents Cattelan, agreed that the terms of the agreement between the sculptor and Cattelan were blurry. But the two diverged on whether that should ultimately matter when it comes to determining who was the true author of these works.

According to Le Monde, Druet must pay 10,000 euros to Perrotin and the Monnaie de Paris. It wasn’t immediately clear whether he intended to appeal the decision, the French publication said.

Pierre-Yves Gautier and Pierre-Olivier Sur, two lawyers representing Perrotin, said in a statement, “beyond this court decision, it is conceptual art that is now protected by the rule of law.”

https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/maurizio-cattelan-authorship-lawsuit-dismissed-1234633671/

up-date 2023/5/19

May 16, 2023 at 2:05pm

JUDGE ALLOWS TWO LAWSUITS AGAINST RICHARD PRINCE TO PROCEED

US District Judge Sidney Stein on May 11 refused to throw out two copyright lawsuits against Richard Prince stemming from the artist’s 2014 “New Portraits” series, as initially reported in Courthouse News. Prince had petitioned for a summary judgment—a ruling absent a trial—in both cases on the grounds that the contested works sufficiently transformed their source material and thus did not infringe on the copyright of the originals.

At issue are Prince’s use of screenshots sourced from Instagram, which he printed onto canvas and appended with his own comments, all without the permission of the original photographers whose work was depicted. Donald Graham, whose 1998 photo Rastafarian Smoking a Joint appears in one of the Prince works, originally filed suit against the artist in 2015. Photographer Eric McNatt in 2016 sued Prince over the latter’s use of a portrait of Sonic Youth’s Kim Gordon, originally commissioned from McNatt by Paper magazine in 2014. Prince attempted the fair-use defense and Stein in 2017 rejected it in relation to Graham’s suit, noting that “the primary image in both works is the photograph itself” and asserting that “Prince has not materially altered the composition, presentation, scale, color palette, and media originally used by Graham.”

The Graham and McNatt suits, both of which may now proceed apace, are similar to that filed against Prince by photographer Patrick Cariou in 2009. Cariou alleged that Prince had lifted photos from his 2000 bookYes Rasta for the artist’s “Canal Zone” series. Judge Barrington Parker of New York’s Second Circuit court in 2013 ruled that Prince’s treatment of the original images—which he variously cropped, splattered with paint, or overlaid with other images—changed them enough that the finished works did not infringe on Cariou’s copyright. However, Stein’s decision of last week arrived amid a changed landscape shaped by the proliferation of social media platforms.

“Portrait of Rastajay92 and Portrait of Kim Gordon make several modifications which are in the Court’s view, both minimal and insufficient to warrant the conclusion that they result in an aesthetic and character different plaintiffs’ original photographs,” wrote Stein in his opinion. “Defendants’ attempt to cast the images as satire or parody fails, and Prince’s stated purpose in creating these portraits has been both inconsistent and has only limited relevance in light of the similarities between the original and the secondary works.”

The court’s decision is likely to affect the outcome of another closely watched copyright case, this one involving a 1981 portrait of iconic rocker Prince taken by Lynn Goldsmith and appropriated by Andy Warhol in a 1984 screen print. The Supreme Court is expected to issue a ruling on the matter this year.

https://www.artforum.com/news/judge-allows-two-lawsuits-against-richard-prince-to-proceed-90559

up-date:

January 26, 2024

Richard Prince and Galleries Settle in Closely-Watched Copyright Lawsuits

Richard Prince and his galleries, Gagosian and Blum & Poe, have reached a settlement in two copyright lawsuits brought by photographers whose images were used without permission by Prince in his “New Portraits” series. The news comes amid years-long litigation over whether Prince’s series, consisting of Instagram screenshots Prince reproduced on canvas and paired with his own commentary, exceeded the boundaries of copyright protections.

Per documents filed yesterday in the Southern District of New York, in the case of Eric Mcnatt v. Richard Prince and Blum & Poe, United States District Judge Sidney H. Stein judge wrote that the defendants are barred from “reproducing, modifying, preparing derivative works from, displaying, selling, offering to sell, or otherwise distributing” the photograph Kim Gordon 1, the Instagram post in which Prince featured Kim Gordon 1, or including the artwork in any book based on the series. Mcnatt, the original photographer, has also been awarded an amount “equal to five times the sales price” for Prince’s artwork sold by Blum & Poe, plus additional costs “incurred by” Mcnatt “as agreed-upon by the parties.”

In an emailed statement to ARTnews, Prince’s studio manager Matt Gaughan said, “After 8 years of litigation while making 8 figure demands for damages and the additional requirement of Richard admitting infringement [the plaintiffs] approached us on the eve of trial to settle for cents on the dollar and no admission of infringement. We’re very happy with that. This settlement allows Richard and all of the artists to move forward with their practices.”

McNatt brought the suit against Prince in 2020, after discovering Prince’s appropriation of his portrait of Kim Gordon, co-founder of art rock band Sonic Youth. McNatt’s image was commissioned for Paper Magazine in 2014.

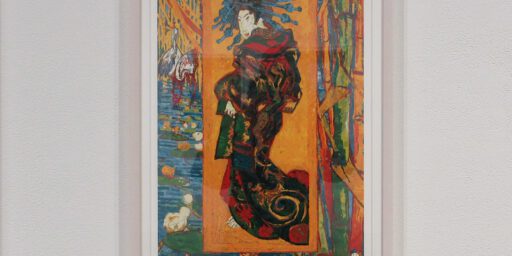

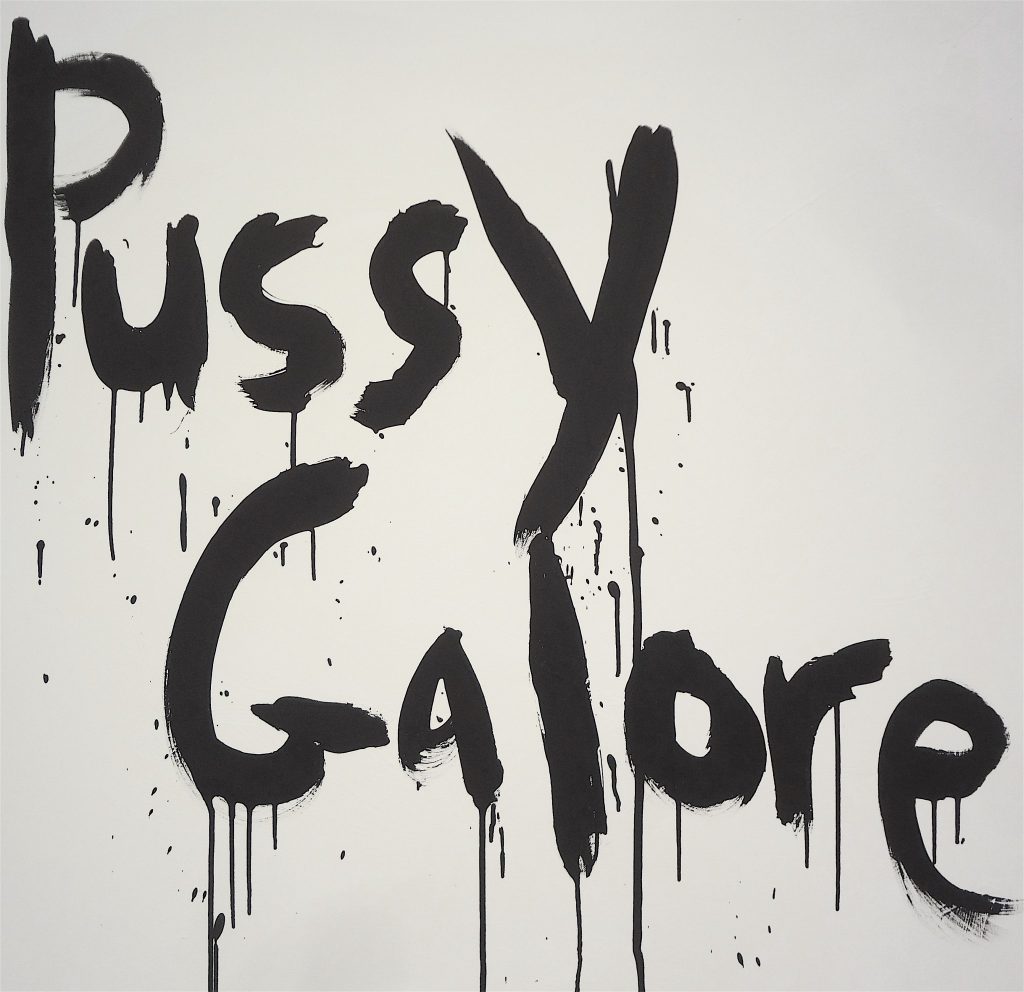

Prince titled his artwork Portrait of Kim Gordon, and added the comment “Kool Thang You Make My Heart Sang You Make Everythang Groovy,” a reference to the 1960s song “Wild Thing” and the 1990 Sonic Youth song “Kool Thing,” sung by Gordon. The nearly 5-foot-tall canvas was exhibited at Blum & Poe’s Tokyo Gallery from April 2015 through May of that year.

Also filed today was a development in Donald Graham v. Richard Prince, Gagosian Inc., and Lawrence Gagosian. The lawsuit concerns the photograph Rastafarian Smoking a Joint, originally taken by Graham and later reproduced by Prince for his first showing of “New Portraits” in an exhibition at Gagosian’s Madison Avenue gallery in 2014. Prince’s artwork, titled Portrait of Rastajay92, was later included in a companion catalog to the exhibition and featured on a billboard promoting “New Portraits” in New York City. Graham filed a cease-and-desist order against Prince, followed by a lawsuit in 2015.

US District Judge Stein wrote that Portrait of Rastajay92 was bound by the same restrictions as Kim Gordon 1: no future reproductions, modifications, distribution, promotions, or sales. Additionally, Graham, like Mcnatt, was awarded expenses amounting to five times its retail price and costs incurred.

Prince and his parties had been attempting for years to have both lawsuits dismissed. In 2017, Stein refused Prince’s appeal, writing in a prior ruling that the “primary image in both works is the photograph itself. Prince has not materially altered the composition, presentation, scale, color palette and media originally used by Graham.”

Prince, who shot to fame for presenting altered versions of the work of other artists, has argued that his practice is protected by fair use exceptions to federal copyright protections, which allow the limited appropriation of intellectual property for purposes such as scholarship, news reporting, and commentary.

Asked about the appropriation controversy in 2016, Prince told Vulture: “I’m not going to change, I’m not going to ask for permission, I’m not going to do it.”

In an earlier, unsuccessful lawsuit, French photographer Patrick Cariou accused Prince of copyright infringement after he learned that Prince’s “Canal Zone” series incorporated photographs from Cariou’s 2000 book, Yes, Rasta. Cariou’s case, which bounced between lower and higher courts for years, was eventually determined by whether a “reasonable observer” would find Prince’s use of the source material sufficiently transformative, defined by the court as imbuing a “new expression, meaning, or message.”

In 2013, New York’s Second Circuit made a landmark ruling that Prince had not exceeded the protection of fair use.

“What is critical is how the work in question appears to the reasonable observer, not simply what an artist might say about a particular piece or body of work,” Judge Barrington Parker wrote for the majority. The precedent set by the case became a touchstone for similar copyright lawsuits brought by artists against powerful industry figures.

In Donald Graham’s original complaint, he accused Prince’ modifications to his photograph of being insufficiently transformative, with only “minor cropping of the bottom and top portions” that left most of the source image “fully in tact,” and “framing the Copyrighted Photograph with elements of the Instagram graphic user interface” such as a line of text Prince wrote that read “richardprince4 Canal Zinian da lam jam”.

Blum & Poe and Gagosian did not immediately respond to an ARTnews request for comment.