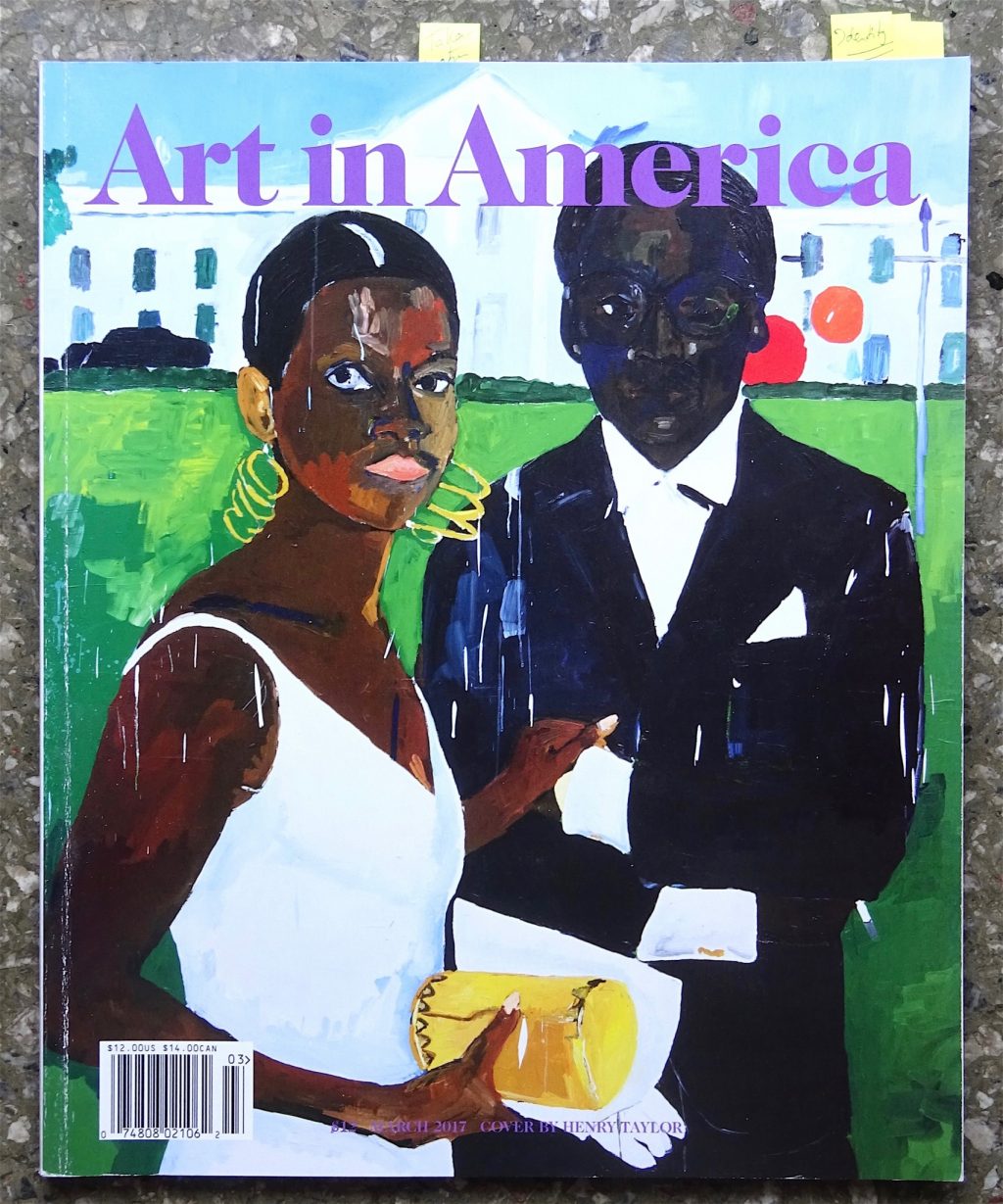

“Black Artist” vs. “Yellow Artist” in the context of “Henry Taylor @ Blum & Poe Tokyo” “Black Artist” vs. “Yellow Artist” in the context of "Henry Taylor @ Blum & Poe Tokyo"

Henry Taylor “Cicely and Miles Visit the Obamas” 2017, Acrylic on canvas, 213.4 x 182.9 cm, detail

Blum & Poe booth @ Art Basel, June 2017

Please cross-check these postings:

“Black Artist” vs. “Yellow Artist” in the context of “Henry Taylor @ Blum & Poe Tokyo” (2018/5/12)

https://art-culture.world/articles/black-artist-vs-yellow-artist-in-the-context-of-henry-taylor-blum-poe-tokyo/

Mark Bradford + Kerry James Marshall: ‘Black Art’ for American Art Flippers (2018/5/14)

https://art-culture.world/articles/mark-bradford-kerry-james-marshall-black-art-for-american-art-flippers/

バーゼル市立美術館の学芸員フィアスコ:「ブラック・マドンナ」(キリスト教) vs. 「ブラック・天皇」(神道) (2018/7/1)

Curatorial Fiasco at the Kunstmuseum Basel: “Black Madonna” (Christianity) vs. “Black Tenno” (Shintoism)

https://art-culture.world/articles/curatorial-fiasco-at-the-kunstmuseum-basel-theaters-gates-black-madonna/

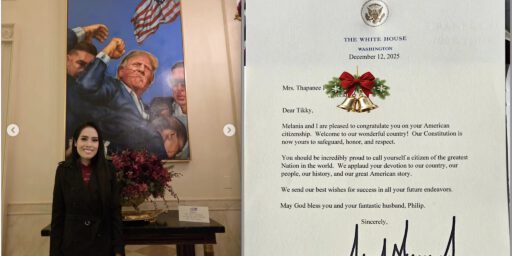

Art in America, March 2017

Henry Taylor “Cicely and Miles Visit the Obamas” 2017, Acrylic on canvas, 213.4 x 182.9 cm, Blum & Poe booth @ Art Basel, June 2017

photo taken with the available light

Thelma Golden, Director and Chief Curator of The Studio Museum in Harlem, New York City, USA

see also:

Is “African American” an appropriate term?

————————-

1971.

“Imagine” Yoko Ono and John Lennon.

2018.

And we are still arguing about “color” as boundary. In a progressing, quickly developing global mobility context, fear of losing its own cultural identity make people act in discriminative ways.

The still running mediocre-painting-exhibition at Blum & Poe Tokyo “Henry Taylor – ‘Here and There’ ” questions identity politics, because Taylor forces us to discuss about the termini “black artist”, “Black Americans”, “artists who are black”, “American artists of African descent who are American artists, and they create American art”.

In the 80’s I travelled as a back-packer around Latin America for one year. The terminology “American art” used by US citizens is more than wrong, because it manifests, still today, an attitude of discrimination, segregation with a notion of supremacy.

Now, let’s change the color, especially from the viewpoint of Japan, where I (= African-European multi-ethnic background) consider myself an artist from Japan.

Should I mention, that my educational background could be defined as the so-called “Christlich-jüdische Leitkultur” in Deutschland?

Italian and German family relatives follow catholic and protestant beliefs. Because of my Japanese wife, I have to pray in Buddhist temples and Japanese Emperor “Tenno”-related Shinto shrines.

Hey, it’s all fucked up, but I enjoy it and I am living a happy life as a human being.

Let’s quote Kerry James Marshall:

“People ask me why my figures have to be so black. There are a lot of reasons.

First, the blackness is a rhetorical device. When we talk about ourselves as a people and as a culture, we talk about black history, black culture, black music.

That’s the rhetorical position we occupy.”

Black-Yellow. This kind of rhetorical device can be used also with the word yellow.

Yellow history, yellow culture, yellow music.

How would you define “yellow artist”, “Yellow American”, “artists who are yellow”, “American artists of Asian descent who are American artists, and they create American art”?

You see, it’s awful, really fucked up, too. And we could rotate, exchange the “colors” in every country of the world.

Hesitating to distinguish between mixed races?

Let’s have a discourse in Japan or in any Asian country about identity politics by adding the layers “gender identity”, “feminism”, “religion”, “spiritual seekers”, “minority culture” and “multiple country origins”. It will end up in discriminative, segregative statements, even in the contexts of scientific terminology and the so-called “Human Enlightenment”.

Unfortunately, in other parts of the world, abstractly speaking, the cultural identity situation is getting worse.

Keeping the above mentioned, problematic ambivalence about being “designed” as black artist or artists who are black in mind, I therefore hesitate to see the Taylor works as “black art”.

If Henry Taylor calls himself a “Black Artist”, I, Mario A, will call myself a “Yellow Artist”.

Let’s have a laugh:

Black Panther Painter vs. Yellow Jaguar Painter.

Why should we rewrite (Western) art history?

100 years ago “White Painting” in the “Western Art Canon” had been already re-contextualized by Gabriele Münter, Oskar Kokoschka, Otto Müller, Vincent van Gogh, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Max Pechstein, Emil Nolde and many more… The faces and bodies are painted in green, red, yellow, black, etc..

Picasso was partly of Arabic origin. Picasso is NOT a WHITE painter.

Basel, 2018/5/12

Mario A

ヘンリー・テイラー @ ブラム・アンド・ポー 東京

「Here and There」

2018年3月24日 – 5月19日

https://www.blumandpoe.com/exhibitions/henry-taylor-3#images

ヘンリー・テイラー「Portrait of Yusuke Nishimura」 2018, Acrylic on canvas, 16 1/16 x 12 5/8 x 11/16 inches

ヘンリー・テイラー「Dr. Ashley…,」2018, Acrylic on canvas, 16 1/16 x 12 5/8 x 11/16 inches

ヘンリー・テイラー「I THINK IT’S TIME TO PRAY」2017, Acrylic on canvas, 35 x 23 1/2 x 3/4 inches, detail

ヘンリー・テイラー 「Apollonia」2017, Acrylic on canvas, 84 5/8 x 22 1/4 x 1 1/2 inches

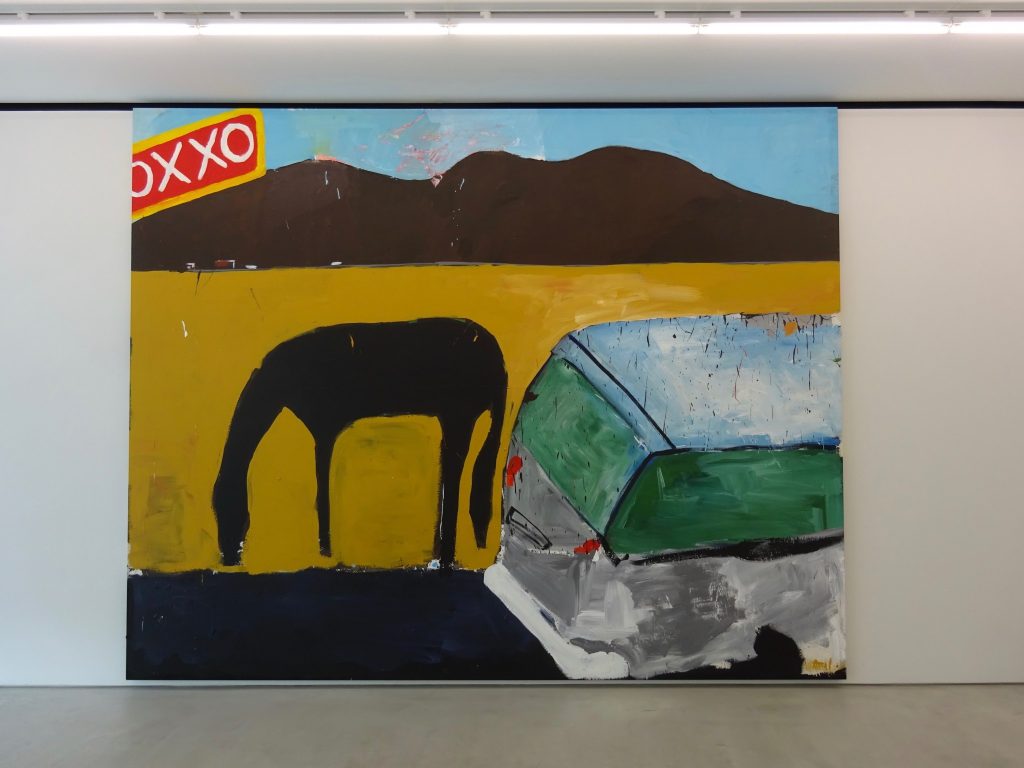

ヘンリー・テイラー「OXXO- Somewhere in Mexico but close to the BORDER」2015-2018,

Acrylic on canvas, 114 1/8 x 142 1/4 x 1 3/4 inches

「Priscilla’s Welcomed Me」2017, Acrylic on canvas, 58 1/4 x 39 x 1 inches

「Priscilla’s Welcomed Me」detail

「Ghana Girl, Gonna be a Woman」2017, Acrylic on canvas, 35 x 27 1/4 x 3/4 inches

「Wow, I’m gonna miss u!」2018, Acrylic on canvas, 13 x 9 5/8 x 11/16 inches

—————-

compare with:

アンビギュイティと差別意識:藤井光の優作「日本人を演じる」を巡って (2018/4/6)

Ambiguity and Discriminatory Consciousness: Outstanding Work by FUJII Hikaru “Playing Japanese”

https://art-culture.world/articles/ambiguity-and-discriminatory-consciousness-outstanding-work-by-fujii-hikaru-playing-japanese/

—————-

up-date, 2018/5/13

The Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles’s Benefit Brunch in honor of artist Henry Taylor

Tribute by

Mark Bradford

Saturday, May 12, 2018

Luminary Table $20,000

Benefactor Table $13,000

Supporter Table $7,500

Charles Gaines, 2018 Benefit Bruch Host and ICA LA Board Member added, “Henry is one of the most important figurative painters working today. What makes his work unique is that it introduces us to the things and people that both concern and matter to him. His figures are presented as subjects, but they are also guides that take us through his idea of the truth of the human condition.”

https://www.theicala.org/en/brunch

—————-

update 2018/5/14:

Mark Bradford + Kerry James Marshall: ‘Black Art’ for American Art Flippers (2018/5/14)

https://art-culture.world/articles/mark-bradford-kerry-james-marshall-black-art-for-american-art-flippers/

update 2018/6/8:

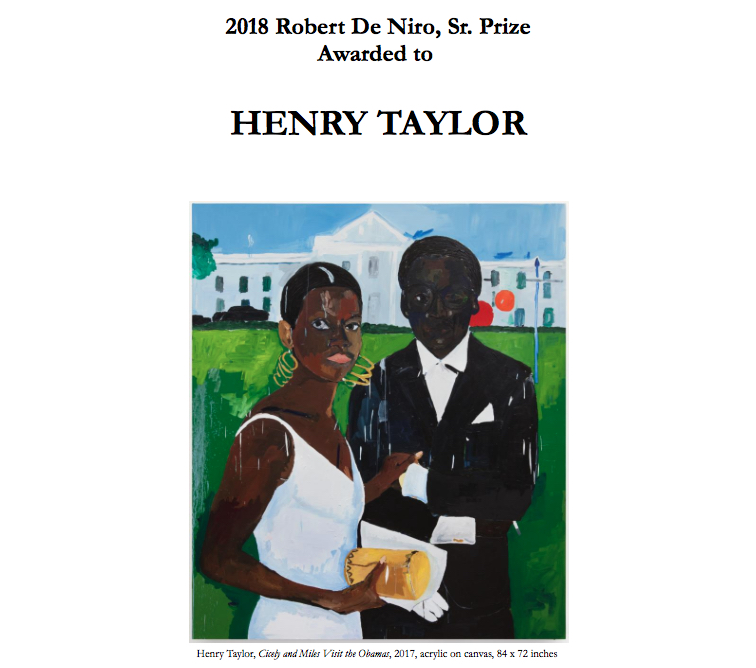

http://www.robertdenirosr.com/prize/

The Estate of Robert De Niro, Sr. is delighted to announce that Henry Taylor is the 2018 recipient of the esteemed Robert De Niro, Sr. Prize. Established in 2011 by Robert De Niro, in honor of his late father, the accomplished painter Robert De Niro, Sr., the prize recognizes a mid-career American artist for significant and innovative contributions to the field of painting. Nominated each year by a distinguished selection committee, Henry Taylor is the seventh recipient of the $25,000 merit-based prize, administer by the Tribeca Film Institute (TFI) for which Robert De Niro is a co-founder. This marks the first time that Henry Taylor has been awarded a solo monetary prize for his achievements in painting.

This year’s selection committee included Sarah Douglas, Editor-In-Chief of ARTnews; Courtney Martin, Deputy Director and Chief Curator of Dia Art Foundation; and Susan Thompson, Associate Curator at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum.

Of Taylor’s work Courtney Martin remarked, “In what feels like a condensed number of years, Henry Taylor has delivered a body of engaging narrative, figural painting. Though the stories attached to the works are often deeply personal, the canvas reveals layers of meanings both universal and formal. He is masterful with color and with compositional arrangements that prick the senses. Taylor’s paintings are a full-on experience.”

“Henry Taylor had the unusual experience of ‘emerging’ in mid-career, becoming known widely as an artist at age 50 or so,” said Sarah Douglas. “Having followed his career closely over the past ten years, and made visits to his studio (whether the permanent one in Los Angeles or the impromptu one at P.S.1), I’ve witnessed, and never fail to be impressed by, his dedication to painting.”

“Whether his subjects are friends and neighbors, local homeless or mentally ill individuals, or prominent cultural figures, each of Taylor’s portraits captures the fullness of a life in a single moment, evoking a distinct sense of mood and creating a profound connection with the viewer,” said Susan Thompson.

“I very much admire Henry Taylor’s lifelong dedication to his work and his continued devotion to painting through his teaching.” said Robert De Niro “I am proud to recognize Taylor’s career through this prize that honors my father’s memory, and I am grateful to the selection committee for their choice of Henry Taylor this year.”

“Good things come to those who wait,” said Henry Taylor.

Henry Taylor was born in Ventura, CA (1958) and received a BFA from the California Institute of the Arts. Recent solo exhibitions include the floaters, High Line Art, New York, NY (2017); This Side, That Side, The Mistake Room, Guadalajara, Mexico (2016); They shot my dad, they shot my dad!, Artpace, San Antonio, TX (2015); and a retrospective at MoMA PS1, Long Island City, NY (2012). His work has been featured in group exhibitions in museums worldwide including the Whitney Biennial, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY (2017); Why Art Matters!, Torrance Art Museum, Torrance, CA (2017); Stedelijk Museum

———

up-date 2018/7/21

Trevor Responds to Criticism from the French Ambassador – Between The Scenes | The Daily Show

—————-

up-date 2018/8/18

Die Tageszeitung, 2018/8/18

„Kein unschuldiges Wort“

Im Bundestag befasst sich Karen Taylor mit Menschenrechten. Ein Gespräch über Kolonialismus, geschützte Räume und die Macht von Quoten.

quotes:

Neben Ihrer Arbeit als Referentin der SPD im Bundestag sind Sie auch politische Referentin des Vereins Each One Teach One e. V., eines Community-Projekts in Berlin-Wedding von Schwarzen Menschen für Schwarze Menschen. Wie ist dieser Verein entstanden?

Unser Verein ist durch das Engagement Schwarzer, vor allem literaturbegeisterter Frauen entstanden, die uns ihr Archiv an afrodiasporischer Literatur vermacht haben. Neben unserer Bibliothek mit knapp 7.000 Werken gibt es zwar auch Formate, die sich generell an den Kiez richten, aber vor allem machen wir Projekte, die ausschließlich für Schwarze Menschen sind. Dazu zählen etwa Nachhilfe, Jugendsupport und eine Beratungsstelle für Erfahrungen mit Anti-Schwarzen-Rassismus. Wir haben den Bedarf gesehen, weil es zwar einige Angebote für Menschen mit sogenanntem „Migrationshintergrund“ gibt, aber kaum etwas, das sich explizit an Schwarze Menschen richtet.

Gerät der Verein auch in Kritik für diese explizite Ansprache Schwarzer Menschen?

Ja, leider werden wir regelmäßig dafür angegriffen, mit Hassnachrichten und vielen Anrufen. Es gab einen größeren Backlash, als wir ein eigenes Screening des Films „Black Panther“ als Schwarzes Event für die Community angekündigt haben. Viele Leute meinten daraufhin: „Wie könnt ihr mir verbieten, dorthin zu kommen, nur weil ich nicht Schwarz bin? Das ist rassistisch!“

Wie gehen Sie mit diesen Vorwürfen um?

Mit Gesprächen. Zum Beispiel erklären wir, dass es sich bei „Schwarz“ um eine Selbstbezeichnung handelt. Wir würden also niemals an der Tür stehen und sagen: „Du kommst nicht rein, du bist nicht Schwarz genug!“ Darum geht es nicht. Wir wollen nicht Menschen ausgrenzen, sondern einen geschützten Raum für Schwarze Menschen schaffen, den es bisher so nicht gegeben hat. Bei Frauengruppentreffen wird auch akzeptiert, dass Männer da nichts zu suchen haben. Und zwar nicht, weil diese Frauen Männerhasser sind, sondern weil sie einen geschützten Raum brauchen, wo sie ihre Erfahrungen mit Gewalt und Diskriminierung verarbeiten und gemeinsame Visionen für die Zukunft entwickeln können. Und genauso etwas braucht die Schwarze Community eben auch.

http://www.taz.de/Sozialdemokratin-ueber-den-Heimatbegriff/!5525323/

John Akomfrah: ‘Progress can cause profound suffering’

Sean O’Hagan, The Guardian, 2017/10/1

For the British artist, global warming, the subject of his ambitious new video installation, is a process rooted in technology and exploitation

John Akomfrah: ‘One of the complex questions I am asking is about the relationship between our locality and the bigger issue of how we belong on the planet.’

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2017/oct/01/john-akomfrah-purple-climate-change

John Akomfrah “Signs of Empire” @ New Museum, New York 2018/6/20 – 9/2

The New Museum presents the first American survey exhibition of the work of British artist, film director, and writer John Akomfrah (b. 1957, Accra, Ghana).

https://www.newmuseum.org/exhibitions/view/john-akomfrah-signs-of-empire

John Akomfrah in Conversation with Gary Carrion-Murayari

Since the early 1980s, Akomfrah’s moving image works have offered some of the most rigorous and expansive reflections on the culture of the black diaspora, both in the UK and around the world. Akomfrah’s work initially came to prominence in the early 1980s as part of Black Audio Film Collective, a group of seven artists founded in 1982 in response to the 1981 Brixton riots. The collective produced a number of films notable for their mix of archival and found footage, interviews and realist depictions of contemporary England, and layered sound collages. In works like Handsworth Songs (1986), Akomfrah and Black Audio outlined the political and economic forces leading to social unrest throughout England. Akomfrah and Black Audio’s works were remarkable for their trenchant political inquiries and consistently experimental approach. Throughout the 1990s, Akomfrah’s subject matter expanded beyond the social fractures of contemporary British society to focus on a wider historical context, from the persistent legacy of colonialism to the roots of the contemporary in classical literature. Moving into the early 2000s, Akomfrah also produced a series of atmospheric works addressing personal and historical memory. In the past several years, his multichannel video works have evolved into ambitious, large-scale installations shown in museums around the world.

2018/8/19 up-date:

Entwicklungshilfe ist ein Auslaufmodell

Ausländische Hilfsgelder versickern gerade in Afrika oft im Sand. Sie können sogar schaden, die Korruption anheizen, die wirtschaftliche Entwicklung hemmen und diktatorische Regime zementieren.

Neue Zürcher Zeitung 18.8.2018

David Signer, Dakar

Es ist schwierig, politisch korrekt über Afrika zu sprechen. Berichtet man über das verbreitete Elend auf dem Kontinent, heisst es, Afrika bestehe doch nicht nur aus Kriegen und Katastrophen, man solle auch einmal über Fortschritte, Modernisierung, Wirtschaftswachstum und den – angeblich – boomenden Mittelstand berichten. Diese beschönigende, verharmlosende Kritik ist seltsamerweise oft von links und aus Kreisen der Entwicklungszusammenarbeit zu hören. Vielleicht soll damit dem Vorwurf, die Hilfe habe nichts gebracht, vorgebeugt werden.

Es heisst auch, man solle nicht pauschalisierend über Afrika reden, am besten vermeide man das Wort «Afrika» ganz. Aber der Mehrheit der Bevölkerung in den meisten Ländern geht es schlecht, der Kontinent bildet ökonomisch immer noch weit abgeschlagen das globale Schlusslicht, und nur schon aus diesem Grund kann man weltwirtschaftlich sehr wohl von Afrika sprechen. Es ist zynisch, so zu tun, als sei die schmale Mittel- und Oberschicht repräsentativ für ein angeblich neues Afrika. Wenn alles so prima wäre, warum möchten dann laut einer kürzlich veröffentlichten Erhebung drei Viertel der jungen Erwachsenen Senegal verlassen, eines der demokratischsten und stabilsten Länder des Kontinents?

Hilfsgelder als Droge

Geht man von den desolaten Zuständen in den meisten afrikanischen Ländern aus, stellt sich die Frage nach den Ursachen. Verteidiger der Entwicklungszusammenarbeit suggerieren oft, es liege am Westen (hier gibt es weniger Skrupel zu verallgemeinern als beim Wort «Afrika»). Das beginnt beim Sklavenhandel, geht über den Kolonialismus und endet bei den angeblich vom Westen errichteten Handelsbarrieren, die Afrika in Abhängigkeit halten und seinen Aufschwung verhindern würden. Das Argument wird seit Jahren gebetsmühlenartig wiederholt, obwohl inzwischen die meisten afrikanischen Staaten, weil sie zu den am wenigsten entwickelten Ländern der Welt zählen, fast alles zoll- und kontingentfrei in die EU exportieren können.

…

Auch der generelle Hinweis auf den (Neo-)Kolonialismus, mit dem an das schlechte Gewissen der Spender appelliert wird, bringt wenig. Das Hauptproblem vieler afrikanischer Länder ist die junge Staatlichkeit. Manche befinden sich immer noch in der Phase des Nation-Building oder sind überhaupt Pseudostaaten, wie Kongo-Kinshasa. Natürlich kann man den Kolonialmächten vorwerfen, dass sie wenig dazu beigetragen haben, tragfähige politische Strukturen zu errichten und frühzeitig Kader auszubilden. Aber ohne Kolonialismus sähe die Situation wahrscheinlich in dieser Hinsicht nicht viel anders aus; möglicherweise wären die Staaten noch weniger ausdifferenziert und fragiler. Im Bereich der vorkolonialen Staatlichkeit unterscheidet sich Afrika radikal von Asien, und das erklärt vielleicht auch, warum sich ein Land wie Vietnam, das gleich mehrmals unter Kolonialismus und Krieg leiden musste, rascher stabilisieren und entwickeln konnte.

continue via:

https://www.nzz.ch/international/auslaufmodell-entwicklungszusammenarbeit-ld.1412317

——–

‘It Was a Monumental Journey’: Kerry James Marshall Unveils a Memorial to the Country’s Groundbreaking Black Lawyers

Artnet news, Sarah Cascone, July 12, 2018

quote: “honoring the accomplishments of African Americans and other minorities whose contributions to US history have all too often been overlooked”

https://news.artnet.com/art-world/kerry-james-marshall-monument-black-lawyers-1316183

…

up-date 2018/9/2

AUG. 23, 2018

Everywhere and Nowhere What it’s really like to be black and work in fashion.

By Lindsay Peoples Wagner

https://www.thecut.com/2018/08/what-its-really-like-to-be-black-and-work-in-fashion.html

2018/9/17 up-date:

From the Archives: Mickalene Thomas on Why Her Work Goes ‘Beyond a Black Esthetic,’ in 2011

BY The Editors of ARTnews POSTED 09/14/18 11:14 AM

“These elements are not necessarily about the black experience; it’s about the idea of covering up, of dress up and make up—of amplifying how we see ourselves. It’s beyond a black esthetic.”

http://www.artnews.com/2018/09/14/archives-mickalene-thomas-work-goes-beyond-black-esthetic-2011/

Quintessentially Chinese art gives way to a global identity

Contrasting Zhang Xiaogang with a young ‘post-passport’ generation

Barbara Pollack

14th September 2018 15:14 GMT

Viewing their artworks, I learned to stop looking for a “Chinese identity” and instead developed the notion of what I like to call a “post-passport identity”.

https://www.theartnewspaper.com/comment/from-chinese-ness-to-a-global-identity

2018/9/21 up-date:

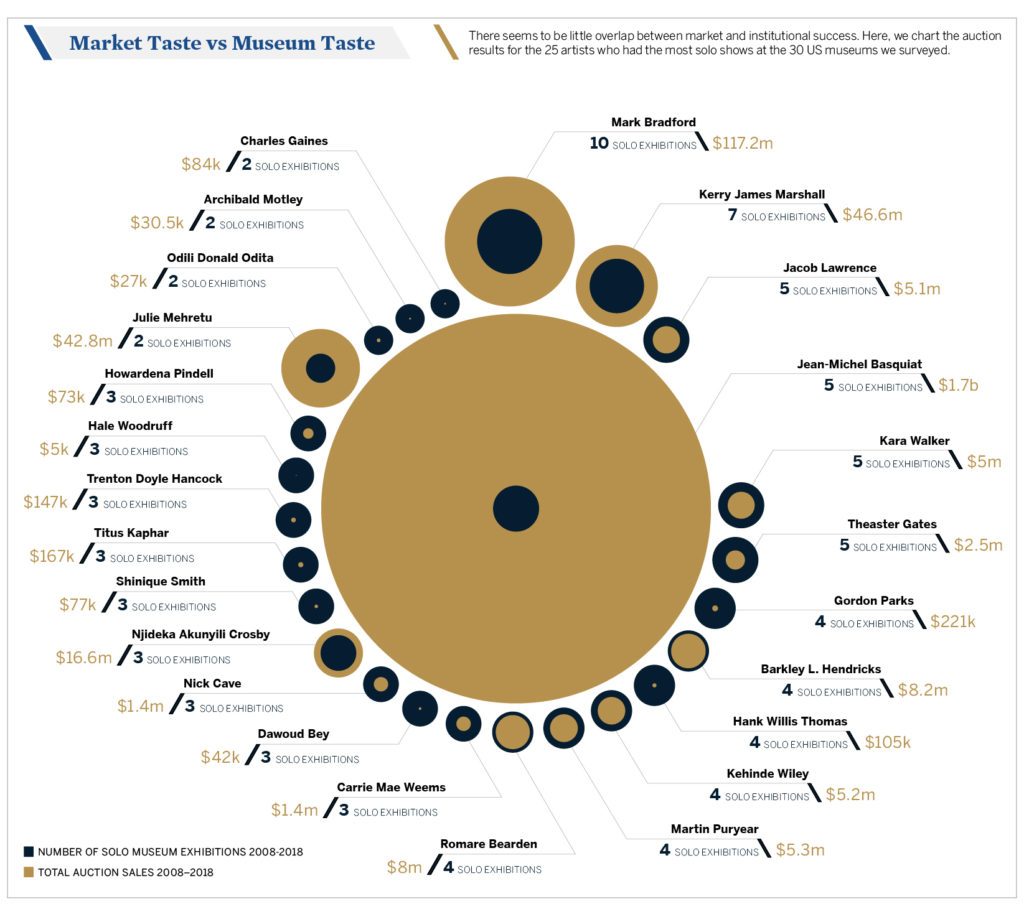

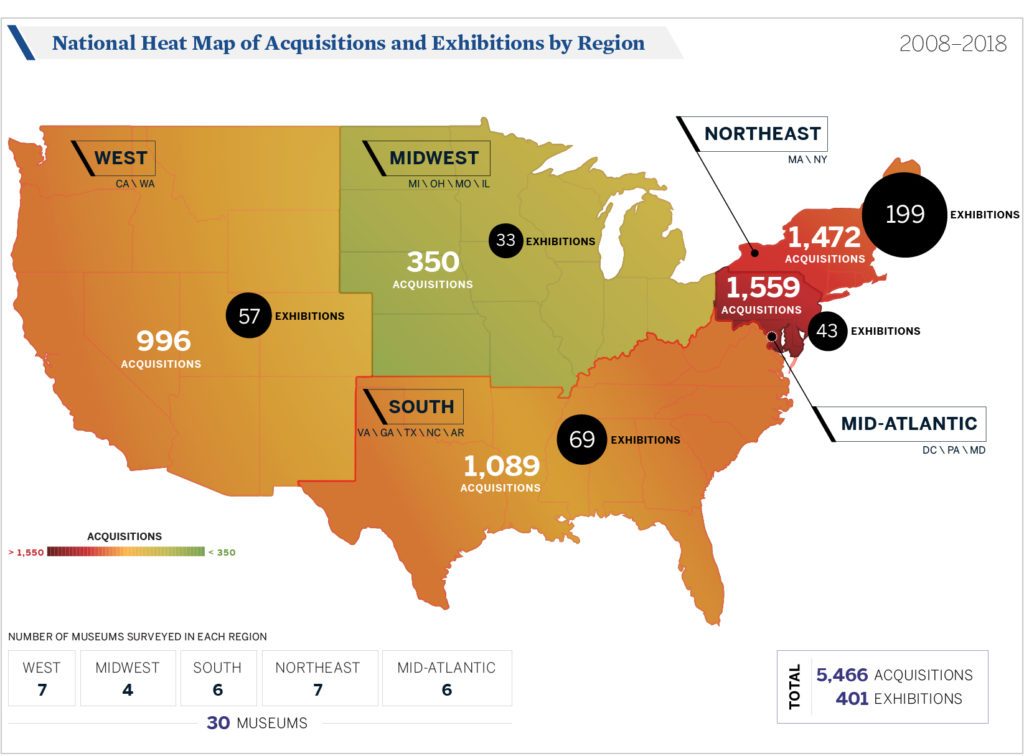

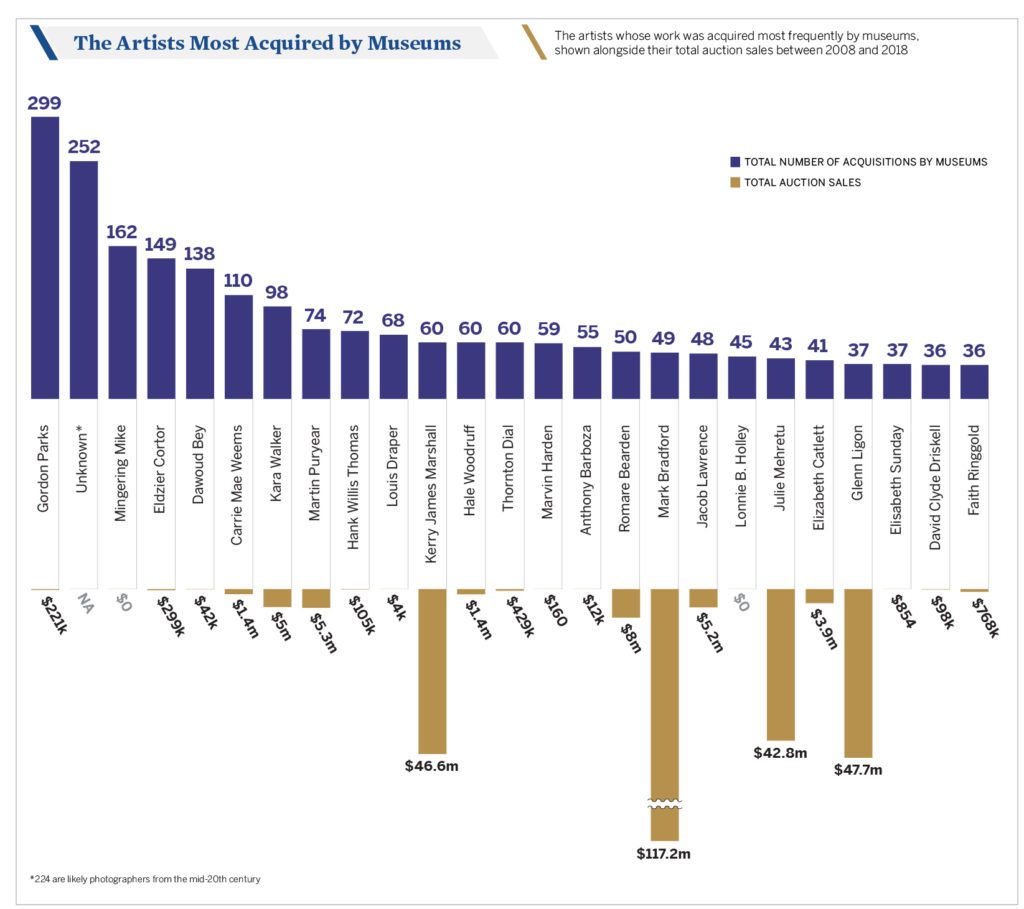

Visualizing the Numbers: See Infographics Tracing the Representation of African American Artists in Museums and the Market

See visualizations of our findings.

Julia Halperin & Charlotte Burns, September 20, 2018

https://news.artnet.com/market/visualizing-numbers-infographics-1351190

African American Artists Are More Visible Than Ever. So Why Are Museums Giving Them Short Shrift?

Our research finds that less than three percent of museum acquisitions over the past decade have been of work by African American artists.

Julia Halperin & Charlotte Burns, September 20, 2018

https://news.artnet.com/market/african-american-research-museums-1350362

Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power

September 14, 2018–February 3, 2019

Brooklyn Museum, New York

https://www.brooklynmuseum.org/exhibitions/soul_of_a_nation

BROOKLYN, NY.- The Brooklyn Museum presents the critically acclaimed exhibition Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power, an unprecedented look at a broad spectrum of work by African American artists from 1963 to 1983, one of the most politically, socially, and aesthetically revolutionary periods in American history. Soul of a Nation considers the varied ways that Black artists responded to the demands of an urgent moment and brings together for the first time the disparate and innovative practices of more than sixty artists from across the country, offering an unparalleled opportunity to see their significant works side by side. The Brooklyn Museum is the only East Coast venue for this exhibition, which was organized by Tate Modern in London and traveled to Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas, in early 2018. The Brooklyn presentation will remain on view through February 3, 2019.

Soul of a Nation features more than 150 works of art in a sweeping aesthetic range, from figurative and abstract painting to assemblage, sculpture, photography, and performance. Among the influential artists of the time highlighted in the exhibition are Emma Amos, Frank Bowling, Sam Gilliam, Barkley Hendricks, Betye Saar, Alma Thomas, Jack Whitten, and William T. Williams. The Brooklyn presentation will also include several works by artist and scholar David Driskell, Suzanne Jackson’s Triplical Communications (1969), and a large-scale draped painting by Sam Gilliam titled Carousel Merge (1971). In addition, a monochromatic work by Emma Amos will be on view, as well as two large-scale paintings by British Guyana-born artist Frank Bowling and an abstract push-broom painting by Ed Clark from the late 1970s, which recently joined the Museum’s permanent collection.

The show begins in 1963, before the emergence of the Black Power Movement later in the decade, with the Spiral collective. This group of New York-based painters, including Romare Bearden, Norman Lewis, and Emma Amos, worked in diverse aesthetic styles and explored the role of Black artists in the struggle for civil rights. Also active in New York at the time was the Kamoinge Workshop, a group of photographers who responded to the lack of institutional support and mainstream representation of Black artists by conducting workshops and producing their own gallery shows and portfolios.

The exhibition goes on to trace how artists across the country continued to work in collectives, communities, and individually during the rise of the Black Power Movement. In Los Angeles, years of urban unrest propelled a number of artists to experiment with assemblage and sculpture. Artists such as John Outterbridge and Noah Purifoy made works inspired by the aftermath of the Watts Rebellion of 1965. Emory Douglas, who served as the minister of culture for the Black Panther Party, founded in Oakland, California, in 1966, created striking graphics and illustrations that became powerful symbols of the movement — 24 of which are included in the exhibition. In Chicago, a group of artists formed AfriCOBRA, whose manifesto and aesthetic philosophy aimed to empower Black communities. Works by its founding members are on display, including Gerald Williams’s Say It Loud (1969), whose vibrant colors, graphic lettering, and use of black figures were emblematic of the AfriCOBRA style. In New York, painters incorporated symbols of protest, solidarity, and Black pride, while many organized for institutional inclusion. Also featured is artist and professor David Driskell, who drew upon similar themes in his painting, as he worked to organize university art departments across the South and promote scholarship of African American art.

The show also addresses formal concerns and aesthetic innovations across abstraction and figuration in painting and sculpture, featuring such works as Sam Gilliam’s April 4 (1969), Barkley Hendricks’s Blood (Donald Formey) (1975), Frank Bowling’s Texas Louise (1971), and Martin Puryear’s Self (1978). With its central triangular form, Jack Whitten’s powerful Homage to Malcolm (1970) recalls the pyramids that Malcolm X visited on a trip to Africa in 1964, and was painted as a memorial to the late activist. Other works show the emergence of integral figures in Black feminism such as Kay Brown, Faith Ringgold, and Betye Saar, highlighting an important moment of visibility for female artists. The exhibition concludes with a section on Just Above Midtown (JAM), the first commercial gallery space dedicated to showing the work of avant-garde Black artists, notably including artists working in performance, such as Lorraine O’Grady, David Hammons, Senga Nengudi, and others.

The timely exhibition extends the Brooklyn Museum’s trailblazing commitment to a vital period in American art, following its exhibitions Witness: Art and Civil Rights in the Sixties (2014) and We Wanted a Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965-85 (2017), as well as the Museum’s major acquisition of 44 works from the Black Arts Movement in 2013.

“With Soul of a Nation, we are honored to highlight the truly exceptional work produced by African American artists during one of the most significant moments in U.S. history and to honor these artists and all those arts professionals, here in Brooklyn and beyond, who have long supported their work,” said Anne Pasternak, Shelby White and Leon Levy Director of the Brooklyn Museum.

Ashley James, Assistant Curator of Contemporary Art, adds: “Artists in this exhibition bravely and variously created art responsive to an urgent time of social, political, and aesthetic rupture, resulting in some of the most striking works created in the late twentieth century. This exhibition adds to an already existing and growing focus on the art produced during the Black Power Movement, an indication of the period’s important and continued resonance with our present as well as the absolute excellence that defines the art of the era.”

Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power shines light on a broad spectrum of Black artistic practice from 1963 to 1983, one of the most politically, socially, and aesthetically revolutionary periods in American history. Black artists across the country worked in communities, in collectives, and individually to create a range of art responsive to the moment—including figurative and abstract painting, prints, and photography; assemblage and sculpture; and performance.

Many of the over 150 artworks in the exhibition directly address the unjust social conditions facing Black Americans, such as Faith Ringgold’s painting featuring a “bleeding” flag and Emory Douglas’s graphic images of beleaguered Black city life. Additional works present oblique references to racial violence, such as Jack Whitten’s abstract tribute to Malcolm X, made in response to the activist’s assassination, or Melvin Edwards’s contorted metal sculptures. Working as a collective, members of the AfriCOBRA group presented images of uplift and empowerment. Barkley Hendricks, Emma Amos, and others painted everyday portraits of Black people with reverence and wit. All the artists embraced a spirit of aesthetic innovation, but some took this as their primary goal, often through experiments with color and paint application.

This exhibition brings together for the first time the excitingly disparate practices of more than sixty Black artists from this important moment, offering an unparalleled opportunity to see their extraordinary works side by side.

Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power is organized by Tate Modern in collaboration with the Brooklyn Museum and Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas, and The Broad, Los Angeles, and curated by Mark Godfrey, Senior Curator, International Art, and Zoe Whitley, Curator, International Art, Tate Modern. The Brooklyn Museum presentation is curated by Ashley James, Assistant Curator, Contemporary Art, Brooklyn Museum.

Leadership support for this exhibition is provided by the Ford Foundation, the Terra Foundation for American Art, Universal Music Group, and the Henry Luce Foundation. Additional support is provided by the Brooklyn Museum’s Contemporary Art Committee, the Arnold Lehman Exhibition Fund, Christie’s, Raymond Learsy, Saundra Williams-Cornwell and W. Don Cornwell, Crystal McCrary and Raymond J. McGuire, Megan and Hunter Gray, the Hayden Family Foundation, Carol Sutton Lewis and William Lewis, Valerie Gerrard Browne, Hales Gallery, Tracey and Phillip Riese, Connie Rogers Tilton, and Jack Shainman Gallery.

Hiro Murai, left, with Donald Glover on the set of “Atlanta”

Hiro Murai on the ‘Atlanta’ Finale and ‘This Is America’ Video

The New York Times, By Joe Coscarelli, May 10, 2018

Season 1 of “Atlanta,” the unpredictable FX show created by Donald Glover, had a black Justin Bieber, an episode-long debate about transgender (and transracial) rights, an invisible car and, in spurts, a plot about an aspiring rapper and his rookie manager-slash-cousin.

Season 2, dubbed “Robbin’ Season,” which had its finale on Thursday night, upped the insanity: a homicidal Michael Jackson stand-inanchored one of two mini-horror movies; the real Michael Vick raced people for money; and a real alligator made a cameo, too.

One main ingredient both seasons had in common? The visual touch of Hiro Murai.

continue at…

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/10/arts/hiro-murai-atlanta-finale-this-is-america-interview.html

Childish Gambino – This Is America (Official Video)

up-date 2022/2/11

What Is Black Love Today?

In a special collaboration between Modern Love and Black History, Continued.

We gathered stories that illuminate how Black people live, and love, in this moment.

Feb. 11, 2022, New York Times

When we invited readers — as well as renowned writers such as Staceyann Chin, Mahogany Browne and Damon Young — to respond to the question “What is Black love today?” we were moved by the strength, resilience and diversity of the stories they told us.

To love, or be loved, while Black in the United States has always been tied to community, country and all the ways in which racism can infiltrate a love life: an unwanted third party to any Black love affair, one that refuses to move out no matter how often or how hard you try to evict it. Race, and the inheritance of racial bias, was a thread through nearly every story we read.

In large cities across the country, 81 percent of Black communities are more segregated than they were 30 years ago. As recently as 2017, 82 percent of new Black marriages were between two Black partners. Yet we weren’t looking solely for stories of intraracial romance and the submissions we received remind us that Black love is far from a monolithic concept. These essays tell of heterosexual partnerships, queer love, open relationships, missed connections and the kind of loving familial bonds that often prove to be among the most complex love stories of all.

It’s been 18 years since the Modern Love column debuted — and in all its iterations, it continues to beguile us. Perhaps that’s because, as the poet Nikki Giovanni once wrote, “We love because it’s the only true adventure.” Every Black love story — like every love story — is a journey into uncharted territory, making us explorers and lovers at the same time.

full text:

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/02/11/style/what-is-black-love-today.html

up-date 2022/8

Convincing artistic statements by Kehinde Wiley.

Henry Taylor: ‘From sugar to shit’

ここに載せた写真は、すべて「好意によりクリエーティブ・コモン・センス」の文脈で、日本美術史の記録の為に発表致します。

photos: cccs courtesy creative common sense