Collector Eli Broad, Who Shaped Los Angeles Art Scene Dies at 87 ロサンゼルスのザ・ブロード

“RIP ELI !! We could and still need a few more like you.

Without your indomitable spirit so many great things would never been accomplished !!!

You were singular in your restless commitment to make LA great and we all benefited from your unrelenting and profound commitment to Los Angeles.”

This beautiful sentences came from influential curator Paul Schimmel, just one hour ago.

Another voice: “You set the bar. We follow. R.I.P. Eli Broad. Thank you for your public generosity and personal kindness.”

The Broads were vivid collectors of MURAKAMI Takashi 村上隆 and KUSAMA Yayoi 草間彌生, giving a strong, necessary impetus to the art practice of these two artists from Japan. From another perspective, The New York Times article rightly mentions the questionable choices of the couple. See below attached texts from the Los Angeles Times with quotes, too. Mr. Broad definitely shaped the Los Angeles art scene, manifested its long overdue importance. After his long-time friend Larry Gagosian opened GAGOSIAN in L.A., a.o. Hauser & Wirth (“& Schimmel” at the beginning) followed, ergo gave the U.S.A. the necessary contemporary art equilibrium, decentralisation, away from the art capital New York City and its auction houses.

Looking forward to visit THE BROAD one day. R.I.P.

THE BROAD ブロード美術館

https://www.thebroad.org

Eli Broad, Whose Generous Patronage Transformed the Cultural Landscape of Los Angeles and Brought the Arts to Many, Dies at the Age of 87

Philanthropist and entrepreneur Eli Broad, who is the only person to found two Fortune 500 companies in different industries and who co-founded with his wife Edye the contemporary art museum, The Broad, died April 30, 2021, at the age of 87.

full text:

https://www.thebroad.org/eli-broad-1933-2021

ブロード美術館について、日本語の情報を参考へ:

BT 美術手帖サイト INSIGHT 2020.1.18

実業家が建てた美術館「ザ・ブロード」はなぜ人々を魅了するのか?

2015年にロサンゼルスのダウンタウンにオープンした「ザ・ブロード」。金融と建設事業で大きな成功を収めた富豪イーライ・ブロードとその妻エディスのアートコレクション約2000点が収蔵・公開されている。オープン以降、圧倒的な人気を誇る同館の魅力を取材してきた。

文=國上直子

(引用)

現代美術を展示する場合、アート・ムーブメントごとやフェミニズム、ポスト・コロニアリズム、マイノリティ、大量消費社会、身体など、定型のテーマでくくられることが多いが、これらは、なじみのない人々にとっては、現代アートへの興味を削ぐ御託になりかねない。ザ・ブロードでは、アーティストごとに作品をまとめて展示することで、こうした「ナラティブ(文脈)」はかなり抑えられている。実際のところ、お仕着せの解説から解放されたザ・ブロードの展示は清々しいものがあり、見る側として、普段どれだけこれらの「ナラティブ」に縛られているか、実感する機会ともなった。

full text:

https://bijutsutecho.com/magazine/insight/21173

オープンから半年で来場者数40万人を記録したThe Broadを徹底解説!

by Discover Los Angeles

Mar 14, 2019

2015年9月にオープンし、オープンからわずか半年で40万人以上の来場者を集めたThe Broad。L.Aで今もっとも注目を集めるスポットの一つとして話題を集めています。2回目となる今回はオープン半年間の詳しい来場者データとともに美術館の魅力をご紹介致しますのでお楽しみに!

Morey Groupによる2015年のNational Art Museum Benchmark reportによれば、The Broadはアメリカ国内のどの美術館よりも幅広い層の来場者が訪れているといいます。民族性においてThe Broadでは来場者の64%が白人ではないという結果でしたが、国立美術館の平均ではわずか23%でした。来場者数の平均年齢においてはThe Broadが32歳、他国立美術館の平均は45.8歳という結果でした。

この他にもリサーチで分かったことが多数あります。

The Broadの来場者の一家庭の平均年収は$65,365だったのに対し、他の国立美術館の来場者の平均年収は$83,967でした。また、The Broadの来場者の17%は年収が$20,000以下だったことも分かっています。

The Broadを訪れている10人中6人はロサンゼルス郡からで、10%がそれ以外(米国内)の地から、さらに10%が海外からの来場者という結果が分かりました。

来場者の3分の1の人が、4人もしくはそれ以上の人数で来場していました。そのうち14%は子供連れでした。

約20%の来場者が、徒歩、バイク、タクシー、公共の交通機関などを使用して美術館を訪れていたことが分かっています。

更に詳しい情報を知りたい方はオンラインで詳しく調べることができます。

full text:

https://www.discoverlosangeles.com/jp/オープンから半年で来場者数40万人を記録したthe-broadを徹底解説!(パート2)

Star-studded gala celebrates Broad museum — and transformation of downtown L.A.

BY DEBORAH VANKIN

September 18, 2015, 11:49 p.m.

(quotes:)

A parade of tiny paper sculptures, all re-creations of cultural institutions along Grand Avenue, glowed atop the dinner tables Thursday night at the black-tie gala for the new Broad museum — fitting as the evening was as much a celebration of downtown L.A., particularly the Grand Avenue corridor, as it was an inauguration of Eli and Edythe Broad’s long-awaited museum of contemporary art.

The LED-lighted centerpieces, inspired by Edythe Broad’s pop-up book collection and designed by Los Angeles artist Renee Jablow, included the honeycomb-like Broad museum amid a boxy Colburn School and a tiny, sweeping Walt Disney Concert Hall, among others.

“This area has come alive,” Mayor Eric Garcetti said. “We’re emphasizing, in L.A., a real street life and kind of assuming the mantle regarding the creative crossroads of the world. L.A. is the creative capitol; it’s shifted west. Not just the institutions, but the creators we house. And the Broad punctuates this.”

The event brought together art world stars such as Catherine Opie, Mark Grotjahn and John Baldessari; civic leaders and government figures like state Attorney General Kamala Harris, and Hollywood celebrities including Gwyneth Paltrow and Owen Wilson.

They all gathered inside a translucent gala dinner tent perched atop a parking structure on Grand Avenue and aglow with gleaming lanterns dangling from the ceiling. On one side: City Hall, luminescent against the inky night sky. On the other side: Disney Hall’s metallic curves and the milky, dimpled facade of the Broad.

Walking to dinner from the cocktail reception held outdoors in front of the new museum, former City Councilwoman Rosalind Wyman — in 1953, the second woman to be elected to the position — said she was almost moved to tears. Wyman helped Dorothy Chandler to address the council back when the latter was raising money to build the Music Center down the street.

“I stood there looking at the Broad and almost cried,” Wyman said. “It’s a jewel. And Disney Hall and Grand Park. It’s amazing when you think what it was like here in the ’50s and ’60s. It was junky, and now, it’s a miracle. It’s just overwhelming.”

The evening started on the red carpet, where in one quick glimpse, onlookers could see artists Doug Aitken, Museum of Contemporary Art Director Philippe Vergne, former L.A. County Supervisor Zev Yaroslavsky and actor Tobey Maguire.

Opie said she is a fan of the Diller Scofidio + Renfro-designed building.

“I was just photographing it from over there,” she said, pointing across the street toward a building under construction, for which she’s creating a series of photographs. “I was shooting it [the Broad] from the roof because it’s just so beautiful.”

Baldessari, looking sharp in a white jacket and sneakers, was quick to point out the global importance of the new museum.

“This isn’t just about L.A. but the world,” he said, “because it’s really a major museum when you think of the caliber of the collection.”

Making his way down the carpet, Takashi Murakami seemed enthused if a bit ill at ease. The artist has five works in the museum’s inaugural exhibition, which he had not seen installed yet. Later, however, when guests were allowed to wander the 50,000 square feet of gallery space during the cocktail reception, Murakami stood in front of one of his paintings, gazed up at his pile of skulls, tracing the lines in his palm.

“What are you doing?” asked MOCA board co-chair Lilly Tartikoff Karatz.

“I just can’t believe I did this,” Murakami replied. “I don’t think I could do that again!”

Jeff Koons said he was honored that his multicolored, stainless steel tulips sculpture had been given a place of honor, front and center, as guests stepped off the escalator into the third-floor gallery.

“The Broad has the largest collection of my work in the world,” he said. “I think of this museum as my Philadelphia; they have the largest collection of [Marcel] Duchamp. The generosity of the Broads, it’s just unparalleled.”

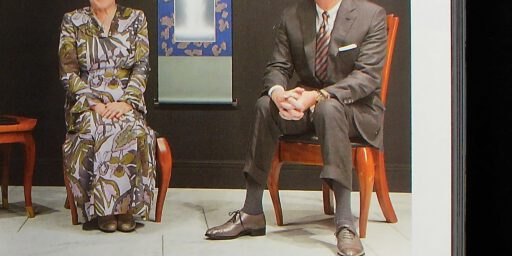

Outside by the bar area, Eli and Edythe Broad, king and queen of this ball, held court in tall pearly white chairs positioned beneath the museum’s “oculus,” where the building’s boxy shell yields to a gentle curve.

“It’s just very gratifying,” Eli Broad said of finally seeing his vision for the museum come to life. Years ago, the Broads had considered Santa Monica and Beverly Hills for the museum, but downtown, Eli said, “is absolutely the right place for it. I’ve always believed Grand Avenue could be a cultural and civic center — and now it’s finally happening.”

Mark Bradford also was in high spirits, greeting passersby in front of his mixed-media piece “Corner of Desire and Piety, 2008.”

“Oh, my God, you look so cuuute,” he said, throwing his arms around a woman in a crinkly, sapphire-blue gown.

Regarding his Hurricane Katrina-inspired piece, which hangs in a prominent spot in the Broad’s third-floor atrium, Bradford was more sober: “I just feel satisfaction,” he said looking up at the work. “It feels like it found a new home, that it’s going to have a whole new conversation here than in New Orleans.”

Standing in front of Damien Hirst’s candy-colored “Chlorpropamide (pfs), 1996,” Barbara Kruger summed up her sentiments: “Wow!” she said, looking around the room. “Just wow.” Then she added: “Eli loves L.A. But this is really a global site for culture, as is the museum across the street,” she said, a reference to MOCA.

At that moment, just as the dinner bells were ringing, LACMA Director Michael Govan descended the escalator and gave a museum worker an enthused thumbs-up. He soon was followed by MOCA’s Vergne, who also gave a thumbs-up as he rode down. In the lobby, Vergne elaborated.

“I used to think more is more,” he said. “But I was wrong. A lot of more is better. I got vertigo in there. My head is spinning. It’s amazing.”

As guests made their way across the street to the dinner tent, live orchestral music filled the air. Atop the ramp leading to the tent’s entrance, Broad architect Elizabeth Diller paused and looked back at the sweeping view of the museum and Disney Hall.

“I’ve never seen it from this point of view before,” she said. “It’s a very disembodied experience — but in a good way.”

The museum’s founding director, Joanne Heyler, called the evening “an immersion in an urban perspective of L.A.”

During dinner — a collaboration between Wolfgang Puck and Timothy Hollingsworth, chef of Otium, next to the Broad — Eli Broad received an uproarious standing ovation even before taking the microphone onstage, but he was quick to deflect the attention.

“Edye was our family’s first collector,” he said, “and she got me interested in art.”

Much lively table-hopping ensued during dinner. At one table, actor Wilson hunkered down in intense conversation with artist Julian Schnabel. Standing by another table, architect Frank Gehry compared notes with Diller.

Paltrow said she was particularly impressed with the scale of the Broad galleries and the art itself. “It feels like it’s an exciting time to be living in L.A.,” she said.

full text:

http://touch.latimes.com/#section/-1/article/p2p-84460511/

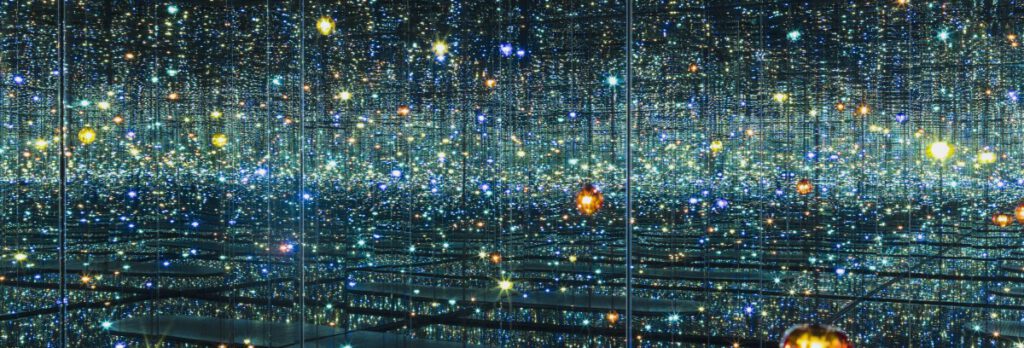

wood, metal, glass mirrors, plastic, acrylic panel, rubber, LED lighting system, acrylic balls, and water

Cross-check:

世界一のアートディーラー、New York City ラリー・ガゴシアンを巡って

World’s No.1 Art Dealer, Larry Gagosian from New York City

https://art-culture.world/articles/larry-gagosian/

A rare, historical picture of Larry Gagosian + Eli Broad in front of the “Leo Castelli Gallery”, New York, 1986.

Leo Castelli became the biggest mentor to Gagosian, who opened his first gallery in Chelsea, 1985.

But when BCAM opened with selections from Broad’s collection in 2008, fully 80% of the 176 works were by artists who had shown with a single gallery — Gagosian, commonly considered the leading commercial powerhouse.

more at:

https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2021-04-30/eli-broad-dies-museums-moca-lacma

Eli Broad, Who Helped Reshape Los Angeles, Dies at 87

The businessman, who made a fortune in home-building and insurance, spent lavishly to try to make the city a cultural capital.

Published April 30, 2021

Updated May 1, 2021, 11:10 a.m. ET

(quotes:)

Few people in the modern history of Los Angeles were as instrumental in molding the region’s cultural and civic life as Mr. Broad. He loved the city and put his stamp — sometimes quite aggressively — on its museums, music halls, schools and politics. He was, until he began stepping back in his later years, a regular figure at cultural events and could be seen holding court in the V.I.P. founders’ room at the Los Angeles Opera between acts.

Mr. Broad played a pivotal role in creating the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art and brokered the deal that brought it Count Giuseppe Panza di Biumo’s important collection of Abstract Expressionist and Pop Art. When the museum teetered on the verge of financial collapse in 2008, Mr. Broad bailed it out with a $30 million rescue package.

He put his name on the Los Angeles landscape as well. The best known of his many contributions to the city is the Broad, a $140 million art museum that he financed himself that houses Mr. Broad’s collection of more than 2,000 contemporary works. It opened in 2015.

He also gave $50 million to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and led the fund-raising campaign to finish the Walt Disney Concert Hall when that project was dead in the water.

…

quote:

Working with civic leaders and developers, Mr. Broad helped shape a far-reaching plan to transform Grand Avenue, in Los Angeles’s neglected downtown, into a cultural and civic hub, with restaurants, hotels, a large park and the Broad. The Walt Disney hall is next door, and the Museum of Contemporary Art is across the street.

The Broad’s opening was one of the most eagerly anticipated cultural events of the past decade. The building, by Diller, Scofidio & Renfro, is eye-catching if unremarkable, but it enshrines the Broads’ remarkable collection.

The New York Times art critic Holland Cotter wrote in a 2015 review that the museum’s layout “should encourage people to make repeat visits, knowing they are likely to see new things each time.”

Still, he said: “The Broad is a museum of an old-fashioned kind. It’s been built to preserve a private collection conceived on a masterpiece ideal and consisting almost entirely of distinctive objects: paintings and sculptures; precious things.”

Along with his art, Mr. Broad collected enemies. Hard-driving, curt and impatient, he was a polarizing figure.

“I’m not the most popular person in Los Angeles,” he wrote in “The Art of Being Unreasonable: Lessons in Unconventional Thinking,” a memoir and business-advice book published in 2012.

No one disputed the claim. Museum directors and trustees often found him meddlesome and impossible to please, determined to run the show and loath to share credit. He hired star architects and then feuded with them, notably Frank Gehry, with whom he had an ongoing feud. (Mr. Gehry designed Mr. Broad’s first house in Los Angeles, but Mr. Broad grew impatient at the rate of progress and hired his own people to build it.) He kept museums in a lather vying for his collection, which, in the end, he decided to lend rather than donate, and exhibit in his own museum.

…

quote:

Mr. Broad began collecting art in the 1960s after his wife began making the rounds of the galleries on La Cienega Boulevard and brought home a Braque print and a Toulouse-Lautrec poster. He spent $85,000 on his first purchase, a drawing by Van Gogh. Works by Matisse, Modigliani, Miró and Henry Moore followed.

Curiosity quickly developed into an acquisitive passion, focused on living artists, whose work he collected in depth.

“I’m not an art historian, but I read a lot, went to museums, went to auctions, spoke to dealers,” Mr. Broad told The Times in 2001. “And I became interested in the art of our time. Why? It reflects what’s happening in our society. And frankly I enjoyed meeting the artists, visiting with them, talking to them about how they see the world, which is far different than people who spend all their time in business.”

He was particularly avid in acquiring works by Robert Rauschenberg, Cindy Sherman, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Cy Twombly and Jeff Koons.

In 2005, he paid $23.5 million for “Cubi XXVIII,” a 1965 work by the American sculptor David Smith, at that time a record auction price for a contemporary artist.

“Measured in dollars, the Broad Collection is currently regarded as a masterpiece, stuffed with works for which only the richest buyers can compete,” Christopher Knight, the art critic for The Los Angeles Times, wrote in 2012.

Still, he added: “Big chunks of his 2,000-piece collection look great and big chunks look uncertain — at best. Critical approval is mixed.”

full text:

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/30/us/eli-broad-dead.html

Eli Broad, billionaire who poured wealth into reshaping L.A., dies at 87

By Elaine Woo April 30, 2021

(quotes:)

But he left his most visible legacy as a cultural philanthropist and broker, whose money and world-class modern art collection made him a powerful and often controversial force on the local arts scene.

In the late 1970s, he became the founding chairman of the Museum of Contemporary Art, and he bailed it out of a financial scandal three decades later with a $30-million grant.

In the 1990s, when the effort to build Disney Hall was falling apart, he took charge of a $135-million fundraising campaign to complete construction in 2003.

That year, he also pledged $50 million to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art to build the contemporary art wing that bears his name.

Calling himself a “venture philanthropist,” he expected his benefaction to bring more than a pat on the back and naming rights. He regarded his donations as investments, the success of which he would judge by their returns, whether in the form of scientific breakthroughs, improved test scores or higher museum attendance.

“I am a builder,” the tall, white-haired Broad once told The Times. “I don’t like to preside over the status quo and simply write checks.”

His demands made some potential recipients think twice about accepting money from Broad. “Too many strings,” said the leader of a major Los Angeles nonprofit, who asked not to be named. Others put it less politely. “Eli is a control freak,” Disney Hall architect Frank Gehry said of his former client in a 2011 segment of CBS’ “60 Minutes.”

Broad was known not only for aggressive involvement in his philanthropic projects but also for a tendency to withdraw his support when developments failed to go his way. These traits were well known in L.A.’s art world, in which he was an unavoidable force.

“The truth is that Eli is L.A.’s most prominent cultural philanthropist, and if you run a museum in this city you have a relationship with him one way or another,” Ann Philbin, director of the Hammer Museum, where Broad once sat on the board, said in a 2010 Vanity Fair article.

Broad’s relationships with the institutions he enriched were often vexing.

In 2010, as a dominant member of the MOCA board, he steered the museum toward the controversial choice of Jeffrey Deitch, a New York gallery owner from whom he had purchased art, to be its new director. In 2012 he forced the resignation of the museum’s longtime chief curator, Paul Schimmel, who had clashed with Deitch over shows involving celebrity artists such as Dennis Hopper that seemed to pander to popular tastes. Several board members resigned in protest, including Ed Ruscha, John Baldessari, Barbara Kruger and Catherine Opie.

In 2013, with MOCA struggling financially, Broad tried to broker a merger between the museum and the National Gallery of Art in Washington, a match that made little sense to many in the museum world. The proposal died amid sharp questioning by critics, including the New York Times’ Roberta Smith, who wrote: “The combination of the domineering Mr. Broad and unusually passive trustees has forced to its knees one of the greatest American museums of the postwar era.”

At LACMA, Broad insisted that the much-needed modern art wing be called the Broad Contemporary Art Museum and personally recruited architect Renzo Piano to design it and a board to govern it. LACMA agreed to his terms without a solid pledge from the multibillionaire to donate works from the 2,000-piece contemporary art collection he had built with his wife, Edythe.

Just before the 80,000-square-foot building’s formal unveiling in 2008, Broad stunned much of the museum world by announcing that he would not be giving LACMA his treasure trove of Warhols, Rauschenbergs and Lichtensteins. Instead, he said he would lend works to the museum from the private art foundation he founded in 1984, an arrangement that he believed would ensure the art he and his wife had amassed over decades would be seen and not stored away.

His decision brought pointed headlines, such as the one accompanying a New York Times story: “To Have and Give Not.” Time magazine’s Richard Lacayo was most blunt, writing on his blog, “LACMA got screwed.”

Although Broad had said over the years that he would not go the way of Armand Hammer and Norton Simon, he ultimately did decide to build his own museum. He settled on a prime downtown lot adjacent to MOCA and Disney Hall for the Broad, the eponymous museum and art lending library that opened in September 2015, part of his vision to cement Grand Avenue as the cultural heart of L.A.

“We believe we have reinvented the American art museum,” he wrote in a 2019 L.A. Times essay on Los Angeles’ cultural evolution.

(quote:)

Their first major purchase came in 1972 when they paid $95,000 for a Van Gogh drawing. Broad eventually found modern art more to his liking and began accumulating works by such artists as Lichtenstein, Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, Cindy Sherman, Jeff Koons, Jean-Michel Basquiat and Damien Hirst.

In the late 1970s, he led a campaign that raised more than $10 million to launch a museum dedicated to modern art. With a personal donation of $1 million, he became founding chairman of the Museum of Contemporary Art and influenced the selection of Japanese modernist Arata Isozaki to design it.

In 1984, he stepped down as MOCA chair after disagreements with the board but remained one of the city’s most powerful art patrons.

full text:

https://www.latimes.com/obituaries/story/2021-04-30/la-me-eli-broad-dead

By Jori Finkel, Los Angeles Times March 20, 2011

(quotes:)

Eli Broad is not known for being effusive, not even when talking about one of his greatest passions: collecting contemporary art. The billionaire philanthropist generally seems more comfortable talking about museum buildings than about the artworks that go inside them.

But earlier this month, Broad opened his Brentwood hilltop home to this writer — and opened up a bit about his personal journey as an art collector, which is expected to culminate in early 2013 with the completion of his new museum downtown. (The 2008 exhibition of his art at the Broad Contemporary Art Museum, the facility he financed on the Los Angeles County Museum of Art campus, was eclipsed by the news that he would not donate his artwork there.)

Though far from a gossip — he tends to tell stories in a rather efficient or clipped form — Broad talked about artists he’s gotten to know, and artworks that have made an impression.

There’s the time that Jean-Michel Basquiat visited his house and stole away to smoke pot in the bathroom. There’s the time that President Clinton was guest of honor for a fundraising dinner and recognized a lounging female figure sculpted by George Segal as a woman he used to date in Arkansas.

There was the night when a “soused” Robert Rauschenberg accepted an award on behalf of Cy Twombly at a New York dinner and would not stop talking. “Five minutes goes by, 10 minutes goes by, 20 minutes, 30 minutes,” says Broad, sitting in view of two Rauschenberg paintings in a gallery-like living room. “I finally got up and asked him to finish. People after that applauded me and said: ‘Thank God you did this.’ But others said: ‘How could you do that to such a great artist?'”

The story suggests something of Broad’s discomfort with sloppy emotional displays. And, yes, he admits that it’s easier for him to analyze the price-per-square-foot of a museum building than to interpret a painting inside. “My first career was in public accounting. I was a young CPA, the youngest in the history of the state [of Michigan], so if I look at a spreadsheet I understand it quickly. Numbers are hard and fast,” says the man who made a fortune in home construction.

“But it’s a very different process looking at a work of art or visiting with an artist,” he says, glancing at a dense Anselm Kiefer painting called “Mesopotamia” that has an enigmatic wire loop (or noose?) embedded in the surface. “It’s hard to explain your emotions when you see a work of art.”

Still, he says he truly enjoys the pursuit that has landed him and his wife, Edythe, on the Artnews top 10 list of collectors worldwide every year for the last 12 years. “Collecting for me isn’t just about buying objects. It’s an educational process, and I think it’s made me a better person. I’d be bored to death if I spent all my time with other businesspeople, bankers and lawyers.”

One artist he considers a friend is Jeff Koons, who started as a commodities broker on Wall Street. But they don’t talk about the financial markets. “We talk about his work, his family, his children,” says Broad, who even got to know Koons’ first wife, Italian porn star La Cicciolina. (“She was rather unusual,” he says.)

Over the years, the Broads have acquired 33 works by Koons (though, notably, none of the erotic “Made in Heaven” work inspired by La Cicciolina), often by fronting the costs for his expensive productions. Other artists represented in depth in their collection include Jasper Johns, Roy Lichtenstein, Andy Warhol, Basquiat, Leon Golub, Chuck Close, Susan Rothenberg and Ed Ruscha.

The Broads also own 120 works by Cindy Sherman, one of roughly a dozen photographers in a collection dominated by paintings. They began buying her prints in the early ’80s for only $100 to $200 apiece after seeing “Untitled Film Stills” at her New York gallery, Metro Pictures. “It was more than photography,” he says of her role-playing experiments. “It was more like theater.”

(quote)

“Twombly, frankly, was an acquired taste,” Broad says. “I was not in love with Twombly the first time I saw one of his paintings. Until you see a whole body of work and get accustomed to it, maybe it’s the shock of the new that Robert Hughes wrote about. I didn’t understand Andy Warhol until he had that great exhibition at [New York’s Museum of Modern Art] that showed it all in context.”

…

Then there’s the living room, with the Rauschenbergs, the Kiefer, a Warhol image of Marilyn Monroe and a Jasper Johns “Flag” painting from 1967. Broad bought the “Flag” in 1999 through Gagosian. “We were lucky to get this,” he says. “It once belonged to Ronald Lauder.

Commentary: The art world knew him as Eli. How Broad was friend and foe to museums

By Christopher Knight, Art Critic

April 30, 2021

(quotes:)

You know you’re a big deal when everyone in your field knows who you are just by hearing your first name.

Lots of rich people populate the international art world. But say “Eli” wherever you go in those serpentine precincts, and everyone knows you mean Eli Broad. In that regard he was the art world’s Cher.

He couldn’t sing, but he especially loved Pop art and its descendants, amassing superlative collections of paintings, sculptures and photographs by Jasper Johns (42 works), Andy Warhol (25), Roy Lichtenstein (35), Ed Ruscha (45), John Baldessari (42) Cindy Sherman (127), Jeff Koons (36) and more. When he committed to the work of an artist, he understood the importance of collecting the artist’s work in depth.

…

quote:

He was instrumental in bringing the stellar collection of 80 works acquired by the groundbreaking Italian collector Giuseppe Panza di Biumo to the new Museum of Contemporary Art as a gift purchase in 1984 — a move that gave instant international credibility to the fledgling institution. But the road soon got bumpy.

I was awakened at 3 a.m. one day by a phone call from Milan from a flustered Panza, who was horrified that Broad, as MOCA board president, was planning to peel off a Mark Rothko painting, maybe one of 11 Franz Klines and perhaps a Robert Rauschenberg “combine” sculpture to send to auction in New York to raise the funds that would pay off the purchase portion of the deal. Fundraising for the purchase had lagged, but rather than write a check — which he certainly could afford — Broad thought it sensible to let the acquisition pay for itself.

The huge outcry when the scheme went public foiled the plan.

The arrangement was strictly rational as a business deal, but it would have wrecked MOCA’s reputation. What important collector would ever engage with the museum again? Broad was never really able to separate his sharp business acumen from his philanthropic activity. He tried to impose his for-profit success on the nonprofit museum sector, regularly creating havoc.

…

quote:

Ironically, for all his vocal support of risk-taking art and of L.A. as a burgeoning center for new art, Broad was ultimately conservative in his collecting habits. When he began in the 1980s, he was forming two collections simultaneously: one personal, which is where he spent large sums of his own money on blue chip art; the other corporate, where he bought work by emerging Los Angeles artists using funds from Kaufman & Broad, his home-building company.

Eventually a number of post-1960s L.A. artists themselves became internationally established, including Chris Burden, Lari Pittman and Robert Therrien. All are now well-represented among the 2,000 pieces in Broad’s museum collection.

But when BCAM opened with selections from Broad’s collection in 2008, fully 80% of the 176 works were by artists who had shown with a single gallery — Gagosian, commonly considered the leading commercial powerhouse. For the cultural life of the city, Broad was a die-hard populist, but there were limits to how far he would go. Tellingly, for all the greatness of his collection — and it is great, with extraordinary works — only Sherman ranks as an untried artist whose reputation he was instrumental in securing.

The rest were first championed elsewhere, and Eli eventually got on board.

full text:

https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2021-04-30/eli-broad-dies-museums-moca-lacma

Eli Broad, an unexpected—and often unreasonable—arts patron

The self-made billionaire helped shape the Los Angeles art scene, while clashing with most of its prominent museum leaders

Jori Finkel

4th May 2021

(quotes:)

Many people in the art world wish that contemporary art were taken more seriously by the rest of society, by people in different fields who are not even drawn to art. They dream about politicians, policy makers, educators and philanthropists alike recognising its value. They have been dreaming, maybe without ever realising it, about Eli Broad, the self-made homebuilding billionaire who was, until his death on 30 April, Los Angeles’s most prominent arts patron without exhibiting any particular affinity for or sensitivity to visual art.

To be fair, he was a dedicated art collector, buying thousands of works by major artists over the course of several decades and ultimately building a museum in Los Angeles, the Broad, to showcase them. He clearly appreciated contemporary art as a financial investment, as a philanthropic tool and as a public good that could play a dynamic role in revitalising cities, including his beloved downtown Los Angeles.

But even when giving tours of his own collection, which began in the 1970s with his wife Edythe’s interests in Van Gogh, Picasso and Matisse before skewing more contemporary, he never sounded particularly interested in individual works of art. He rushed friends through museums if they lingered too long. His approach to art was curiously brisk, efficient and frugal, traits he brought to almost every interaction or transaction, which were hard to tell apart.

When he invited me to his hilltop Brentwood home for an interview in 2011, not long after announcing his plans for the Broad, he shared some stories about his friendships with artists such as Roy Lichtenstein and Jeff Koons, whose mirror-polished, stainless steel Rabbit stood on a pedestal in the entryway. “I’d be bored to death if I spent all my time with other businesspeople, bankers and lawyers,” he said.

Yet when he spoke about individual works of art, he mainly talked about the acquisition process or provenance. He disclosed that one early acquisition, his 1933 Joan Miró painting, had previously been owned by Nelson A. Rockefeller, who had to liquidate it along with much of his art to finance his presidential campaigns. And, in a favourite story, he recalled scooping up Cindy Sherman’s Untitled Film Stills from Metro Pictures in the early 1980s, when they sold for $150 to $200 each. He could not say why he liked them.

…

quote:

The most revealing stories about him date to the early 1980s, when he helped to create the city’s new Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA). When Count Giuseppe Panza di Biumo offered to sell MOCA a trove of works by Rothko, Kline, Rauschenberg and their contemporaries, Broad helped with the negotiations. But he also negotiated behind the museum’s back to buy the collection for himself and never contributed any money for the acquisition. He continued to assert his will there on matters small and large, strong-arming other trustees. One artist on the board, Robert Irwin, who famously abandoned his Los Angeles studio in 1970 to spend time in the Mojave as he shifted from making art objects to making art out of light, has said that his clashes with Broad drove him back to the desert.

Later, when Broad was a trustee at the Hammer Museum, the newly appointed director Ann Philbin stood her ground in 1999 to prevent him from using funds from the $30.8m sale of Leonardo da Vinci’s Codex Hammer to create the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Center at UCLA. He promptly left the board. After that, as a trustee at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (Lacma) who yielded inordinate power thanks in large part to his $60m donation towards an expansion (more than all the other trustees combined), he helped to handpick Michael Govan as the director. In a flush of excitement, Broad once compared Govan to Bill Clinton in his ability to connect with people, but the two had a falling out in 2008, with Broad telling The New York Times, just weeks before the opening of the Broad Contemporary Art Museum at Lacma, that he was not giving his collection to that museum.

He returned to MOCA in late 2008 during its near-death financial crisis, offering a $30m bailout with more strings attached than a marionette. The gift consisted of $15m doled out over five years to “support exhibitions” in a way that allowed Broad to manage—or micromanage—the institution and another $15m to match endowment gifts. And, as I later reported in the Los Angeles Times, the gift also had a clause requiring that MOCA remain independent and not be acquired for ten years by “any museum located within one hundred miles of [its] Grand Avenue facility,” excluding “educational institutions or museums affiliated with educational institutions.” In essence, he prevented Govan from taking over MOCA when, five years later, a merger with Lacma was proposed.

I personally do not think there is anything wrong with buying art as an investment or using art as a tool for urban planning or revitalisation, which the Broad museum has done with great success. Before Covid shut down the city, the museum and its restaurant, Otium, had brought bustling street life to the area and changed the Los Angeles museum-going demographics to include younger, more diverse audiences, both of which are significant accomplishments.

But I do think understanding Broad’s priorities helps to explain why he found himself at odds with so many cultural leaders here. Yes, as most of his obituaries describe, he dramatically shaped the Los Angeles art scene, but so did the museum leaders who stood up to him. It was not a pleasant process.

https://www.theartnewspaper.com/feature/eli-broad-an-unexpected-and-often-unreasonable-arts-patron

up-date 2021/5/14

How will California’s arts institutions recover?

via New York Times

(quotes:)

Your latest piece explores the status of some of LA’s biggest cultural institutions as they emerge from the pandemic. What will you be watching most closely in the recovery?

I’ll be watching three things.

1. Attendance: Will people feel safe enough to go out? The Hollywood Bowl announced this week that it is starting shows again. There were long virtual lines for tickets, but we’ll see how that is going forward. The real question here — and in other cities, like New York — is, will people be willing to go to indoor spaces, from Disney Hall to the LA Opera to any one of 50 small theaters scattered around area? We won’t know until the fall. The numbers here — COVID transmission, hospitalization and deaths — are way down, while vaccinations are up, so that’s encouraging.

2. Money: Arts institutions are struggling and in fact were scrapping for dollars even before. There is a lot of competition for philanthropic dollars coming out of this pandemic.

3. Transit: A critical question is the success of the $120 billion program to build and expand the mass transit system here. Traffic has increasingly been one of the biggest obstacles to getting people to concert and theater halls, particularly in downtown Los Angeles. That could really change when these new lines begin opening up. Case in point: A new metro stop is opening across the street from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, coinciding with the date that the new $650 million David Geffen Galleries are scheduled to open.

And, of course, Eli Broad, whom you described as “part billionaire philanthropist, part civic bulldozer,” recently died, leaving big shoes to fill. But as you and others have noted, there are questions about whether that mode of arts patronage by a singular kingmaker is good for the Los Angeles of the future. So what might be next?

This is a key and nuanced question: Not only, “Is there another Eli Broad waiting in the wings?” but more, “Is that the future of fundraising here? Does this region need — or want — that kind of powerful figure moving forward?”

I think a corollary of that is whether some of the new wealth in California — tech money, to use the shorthand — is going to start flowing into the arts. It really hasn’t happened yet in a big way in LA, but that could sure change given what’s happened with the stock market since January. You could find a cast of new characters writing checks, rather than some single domineering figure.

full text:

https://artdaily.cc/news/135640/How-will-California-s-arts-institutions-recover-#.YJ7deC2B2Rs

Today’s bonus, おまけ:

The BROAD Museum Opening Gala in Los Angeles September 18, 2015

Cindy Sherman

Ed Ruscha and Danna Knego

Wendi Murdoch (in 2015)

Mark Bradford and Gwyneth Paltrow

John Currin and Rachel Feinstein

Kamala Harris, today’s Vice President of the United States of America

ここに載せた写真とスクリーンショットは、すべて「好意によりクリエーティブ・コモン・センス」の文脈で、日本美術史の記録の為に発表致します。Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial-NoDerivative Works photos: cccs courtesy creative common sense