日本人は幸せな国民。令和8年1月11日、TBS テレビ・JNN世論調査:高市内閣支持率78.1% 先月調査から2.3ポイント上昇 Japanese people are happy people. January 11, 2026, TBS TV / JNN opinion poll: Takaichi Cabinet approval rating at 78.1%, up 2.3 points from last month's survey

令和8年1月11日現在、日本国民の78%が高市早苗首相の政権運営を支持している。

こうした数字は「通常」独裁政権や専制政治の共産主義中国でしか見られないものだ。

JNN・TBSによる調査であるため、我々はこの結果を真剣に受け止めている。

日本は米国の属国としての役割に満足している。

日本人は幸せな国民。

日経平均株価は本日、史上最高値54,110.50を記録、1 US Dollar = 158.44円。

東京、令和8年1月15日

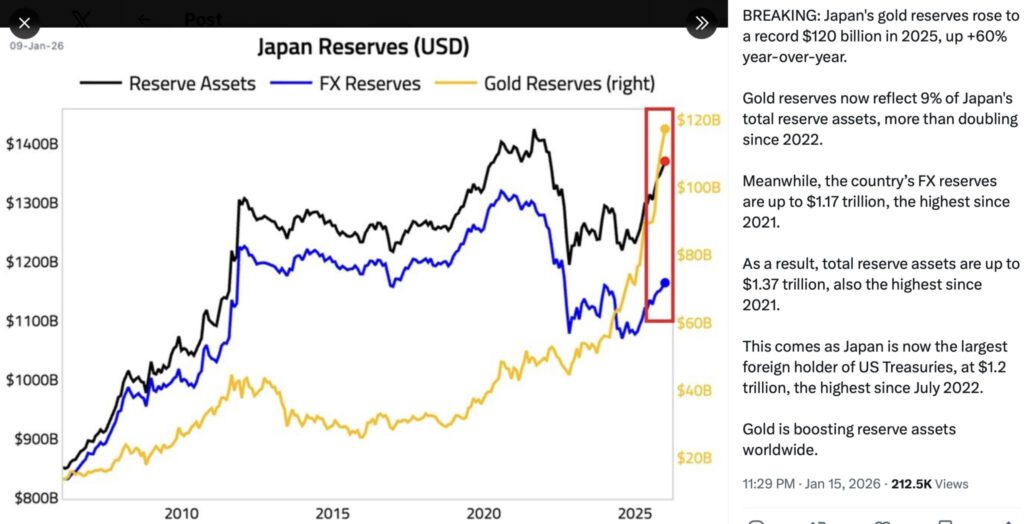

https://x.com/KobeissiLetter/status/2011808031684632632/photo/1

As of 11 January 2026, 78% of the Japanese population approves of the work of Prime Minister TAKAICHI Sanae’s government.

These are figures that ‘normally’ only appear in dictatorships or autocratic, communist China.

We take this survey seriously because it comes from TBS TV/JNN.

Japan is content in its role as a vassal state of the United States.

Japanese people are happy people.

The NIKKEI today at all time high @ 54,110.50; 1 US Dollar = 158.44 Japanese Yen.

Tokyo, 2026 Jan. 15

高市内閣「支持できる」78.1%(+2.3ポイント)

高市総理が通常国会冒頭に衆議院を解散するかどうか近く最終判断するとみられる中、最新のJNNの世論調査で、高市内閣の支持率が78.1%だったことがわかりました。

https://newsdig.tbs.co.jp/articles/-/2394832

Source:

https://x.com/tondeiruHASU/status/2000939031807627736

ハマルキ @tondeiruHASU、11:40 PM · Dec 16, 2025

山口敬之が娑婆でのうのうとして、政治家共と2ショットなんか撮れてる時点で「日本に於いて性犯罪の対応は酷い」のが事実なのは明らかだろ

なのに被害者叩きに一生懸命な奴らが、ジャーナリストとか名乗ってる

It’s blatantly obvious that the way Japan handles sex crimes is terrible, given that YAMAGUCHI Noriyuki is living it up in the secular world and able to snap two-shots with those politicians.

And yet, the folks desperately bashing the victim are the ones calling themselves journalists.

2026 Jan 18 update:

COMMENTARY / JAPAN

Feminism’s failures and the secret to Takaichi’s success

She succeeded through merit in a system rigged against her

BY WAKA IKEDA, Jan 16, 2026

Just three months ago, in October, Japan saw two historic firsts: Sanae Takaichi became the nation’s first female prime minister and Satsuki Katayama was appointed the first female finance minister.

Many in the liberal media and Takaichi’s critics quickly labeled her “hawkish,” “anti-women” and “anti-gender equality,” with National Public Radio in the U.S. declaring, “She broke the glass ceiling, but she is no feminist.”

Some news outlets in Japan went even further, labeling her meiyo dansei (an honorary male) — a woman who succeeds by abandoning women’s interests. Media coverage at home and abroad obsesses over her opposition to selective separate surnames and same-sex marriage while systematically ignoring her legislative record on protecting women and children. The Associated Press, for example, reported that she voices “old-fashioned views favored by male party heavyweights.”

Yet polling after Takaichi took office in October showed that she had a whopping 92.4% support among young adults in Japan ages 18 to 29, with young women supporting her at an even higher rate than young men. That popularity has continued and gained enough momentum for the prime minister to call for a snap election she believes will give her the public backing she needs for her agenda.

This paradox reveals less about Takaichi than about how Japanese feminist discourse has narrowed into an ideological straitjacket that excludes nuanced positions and silences majority voices. It resembles the cancel culture and labeling hegemonic trends found globally in which ideological extremes serve as the litmus test of what A or B is or is not.

Takaichi’s overall popularity is indisputable. As already mentioned, a Sankei/FNN poll found that she enjoyed 92.4% support among 18- to 29-year-olds and 83.1% among those in their 30s. Yomiuri reported 80% support among 18- to 39-year-olds. This isn’t elderly conservatives — it’s the generation supposedly most committed to progressive gender politics.

To understand this paradox, examine Takaichi’s actual policy record. In 2009, she introduced legislation strengthening the Act on Punishment of Child Prostitution and Child Pornography. After years of persistent advocacy — repeatedly submitting bills even after initial failures — the reform passed in 2014, enhancing protections for children against sexual exploitation. This included criminalizing simple possession of child pornography, a significant strengthening of Japanese law that aligned with international standards.

In November 2025, Takaichi instructed the justice minister to examine criminalizing the purchase of sexual services — targeting buyers rather than sellers. “Direct the minister of justice to conduct necessary examinations regarding regulation of prostitution-related activities,” she stated during Diet questioning, receiving bipartisan applause. This aligns with the Nordic model of addressing prostitution by punishing demand rather than criminalizing vulnerable women. Current Japanese law punishes solicitation but not the purchase itself, creating an asymmetry that many feminists have criticized for decades.

Takaichi’s official platform explicitly commits to ensuring women don’t “give up their careers due to caregiving responsibilities” and creating environments where “women don’t give up social activities due to menopause or age-specific health issues.” Takaichi has publicly discussed her own experience with menopause and is currently caring for her husband after he suffered a stroke, giving her firsthand knowledge of the caregiving burdens Japanese women face while trying to maintain careers.

These aren’t symbolic gestures. They are concrete policies addressing sexual violence, economic precarity and caregiving burdens. Yet media coverage focuses exclusively on her conservative positions on family structure, as if feminism must be all-or-nothing.

I personally support selective separate surnames and female emperors. I disagree with Takaichi on these issues. But I can simultaneously recognize her achievements on child protection, prostitution law reform and women’s health policy. This apparently simple positioning on some issues while disagreeing on others — seems impossible for many media and academic elites.

A European scholar recently told me Europe portrays Takaichi as “anti-woman, opposed to gender equality.” When some in the European media asked for my perspective, I explained: “Takaichi is enormously popular in Japan. She came from a humble family, worked her way through university and became prime minister in a male-dominated, hereditary political system. In an era where oya gacha (birth lottery) determines life outcomes, she represents ‛effort can succeed.’ As a feminist and parent, I want to support that model.”

Sadly, none of this appeared in the coverage. European media, like Japanese media, too often publishes narratives fitting predetermined frameworks. Nuanced positions don’t fit the template.

When I ask women outside the media and academia about Takaichi, nearly all support her. Their reasons? “Unlike elderly male prime ministers who attend expensive Ginza hostess clubs, she stays home studying.” “Her explanations are clear and direct.” “She’s smiling and respectful, even under pressure.” One young professional told me: “She works until 3 a.m. studying policy. Previous prime ministers were at fancy dinners.” Men’s reactions surprised me: “I’m male but happy a woman is finally prime minister — it shows Japan can change.” “She’ll try new things our country needs.” “Finally, someone who talks about the future, not the past.”

These aren’t sophisticated policy analyses. They’re observations about character, work ethic and representation. But they explain the polling data better than academic theories about false consciousness. Young Japanese see in Takaichi something elites dismiss: a woman who succeeded through merit in a system rigged against her, who acknowledges most women’s day-to-day struggles (menopause, caregiving and sexual exploitation).

This gap between elite interpretation and popular support reveals class dimensions in Japanese feminism. Journalists and academics in secure positions emphasize systemic reforms such as family names, marriage definitions and representational parity. For precarious workers or women balancing caregiving with careers, these seem abstract compared to protection from sexual exploitation, economic opportunity or menopause support.

Takaichi offers conservative feminism. It is an advancement within existing structures rather than revolutionary transformation. She prioritizes concrete protections (child safety laws, prostitution reform) over structural changes (family registry restructuring). She emphasizes merit and opportunity over quotas and outcomes. This isn’t anti-feminist. It’s a different feminist tradition, one that resonates with Japan’s silent majority.

The reflexive dismissal of this approach as “not real feminism” explains why feminist movements struggle to mobilize broad support despite Japan ranking 118th of 148 countries in gender equality. When high percentages of young women support a leader academic feminists reject, either the young women misunderstand their interests or the academics misunderstand feminism’s purpose.

Japan’s feminist discourse faces a choice: maintain ideological purity or build effective coalitions. The current approach — treating separate surnames and marriage equality as litmus tests that override all other considerations — alienates potential allies and ignores concrete achievements.

Takaichi has strengthened child-protection laws, directed prostitution law reform, championed caregiving support and acknowledged women’s health needs while breaking barriers in male-dominated politics. She’s done this while holding conservative views on family structure.

These facts are not mutually exclusive. One can oppose her position on family names while applauding her work protecting children from sexual exploitation. One can disagree on surname equality while supporting her menopause health initiatives.

A movement that cannot accommodate this complexity — that insists feminists must agree on everything or be dismissed as traitors — consigns itself to irrelevance. The question isn’t whether Takaichi fits academic definitions of feminism. It’s whether Japanese feminism can evolve beyond binary thinking to achieve its stated goals: meaningful equality and opportunity for all women.

The stakes are higher than academic debates. When Canada’s Kim Campbell served just four months as prime minister in 1993, her brief tenure reinforced stereotypes about female leadership — Canada has not elected another female prime minister in three decades. If Takaichi’s government fails, critics will blame her gender, not her policies or political circumstances. Japan’s first woman prime minister deserves evaluation on her record, not impossible standards that no male predecessor faced.

Perhaps in Japan, no one is feminist enough — not because women lack commitment to equality, but because intellectual discourse has become so rigid and, in some cases, unrealistically ideological that it excludes most paths to actual advancement.

The 92.4% youth support for Takaichi suggests the silent majority has already moved beyond these narrow frameworks. The younger generations understand what media elites cannot: that feminism can take multiple forms, that protecting women from sexual violence matters as much as symbolic representation and that concrete policy achievements deserve recognition even from ideological opponents.

Academic feminism can join them or continue shouting into an ever-shrinking echo chamber.

Waka Ikeda is a Tokyo-based freelance journalist and researcher/journal manager at the Youth Research Institute in Budapest.

Update 2026/1/21

Remarks by Minister KATAYAMA Satsuki

Minister of Finance and Minister of State for Financial Services

“Japan’s Turn”

of the 56th Annual Meeting of the World Economic Forum

Davos, Switzerland, January 20, 2026

Introduction

Good morning, everyone. It is a great honor to join you today at this “Japan’s Turn” session.

Since the Takaichi Cabinet took office last October, the government has worked together to build a “strong Japanese economy” through “responsible and proactive public finances”. Optimism toward these changes is growing. In a recent survey of young adults, confidence in politics jumped from about 20 percent to over 50 percent, and almost 50 percent viewed Japan’s future as bright, citing political change and expectations for the new administration. Japan’s nominal GDP has surpassed 4 trillion US dollars (600 trillion yen). Capital investment is at record highs, and wages have risen over 5 percent for two consecutive years. The Nikkei Average is now about five times its 2012 level. These results show that Japan is shifting from a deflationary, cost-cutting economy to a dynamic, growth-oriented one driven by bold investment and productivity gains. Today, I would like to outline the three key pillars of our growth strategy to turn this momentum into sustainable progress.

Strategic investment in priority areas

The first pillar is strategic investment in priority areas. In a country facing future population decline, achieving a “strong Japanese economy” requires strategic fiscal action based on responsible and proactive public finances. By strengthening Japan’s supply structure and raising growth, we aim to lift incomes, restore consumer confidence, and create a virtuous cycle of improving corporate profitability. We are advancing bold and strategic investments that enhance growth and resilience against potential crises to strengthen Japan’s supply capacity. More concretely, we will provide proactive public‑private investments to address risks such as economic, food, energy and resource security. Through delivering products, services, and infrastructure that help solve the global challenges, we will drive Japan’s further economic growth. For example, we are strengthening the semiconductor supply chain through initiatives such as the “Rapidus Project”, which would enable domestic production of cutting-edge 2-nanometer chips. We are also advancing “Physical AI,” which would enable autonomous robotic assistance and unmanned plant operation by aggregating and training high-quality data. We aim to achieve more than 330 billion US dollars of public and private sector investments in the AI and semiconductor sectors by improving predictability for the private sector through over 66 billion US dollars of public support. These key measures for building a “strong Japanese economy” are also reflected in the 2026 tax reform. Specifically, we will introduce tax incentive measures for promoting domestic investment in high-value- added assets. In addition, we will establish a new category under the R&D tax system, designed to incentivize corporate R&D in national strategic technology domains such as AI, quantum, and biotechnology.

Unleashing Japan’s economic potential by leveraging the power of finance

The second pillar is to unleash Japan’s economic potential by leveraging the power of finance. To this end, we will develop a comprehensive financial services strategy by the summer of 2026 and put the strategy into action in close collaboration with the private sector. To create a virtuous cycle of capital that supports economic growth and raises household incomes, the government has been advancing an initiative to “Promote Japan as a Leading Asset Management Center”. For households, we implemented a fundamental revision of the NISA —Japan’s tax-exempt investment scheme for retail investors, in January 2024. The new NISA is now a permanent scheme on tax‑exempt holdings, and the annual investment limit has been expanded. As a result, the number of NISA accounts has increased to about 27 million, meaning one in four Japanese adults holds a NISA account. Participation is growing across all generations, including younger people. Going forward, we will further enhance NISA. Japan’s household financial assets now exceed 15 trillion US dollars (2,200 trillion yen), but nearly half of these assets remain in cash and deposits. This proportion is significantly higher than in the United States. Furthermore, there is a substantial gap in the investment returns on household financial assets between Japan and the United States. If the proportion of equities and investment trusts in household portfolios were to increase, greater portion of the fruit of economic growth would be returned to households in the form of investment income. We are already seeing positive signs. The balance of household risk assets has reached an all‑time high. Capital investment by corporates is also at record levels in nominal terms. Going forward, strategic public‑sector initiatives is expected to catalyze private investment. In addition, more than 90 percent of the companies listed on the Prime Market have disclosed their business plans that reflect capital cost and share price considerations. This signals a clear shift in corporate mindset. With respect to listed companies, Japan has steadily advanced corporate governance reform. The market capitalization of the Tokyo Stock Exchange now stands at about 8 trillion US dollars (1,200 trillion yen)—about four times its level at the end of 2012. The reform has been well received by investors and market participants both in Japan and abroad. At the same time, rising corporate cash holdings has raised concerns about suboptimal allocation of management resources. In response, the FSA and the Tokyo Stock Exchange are preparing to revise the Corporate Governance Code by the summer of 2026. Furthermore, we developed a comprehensive plan last month to ensure that Japan’s regional financial institutions can play a greater role in supporting local economies amid the aging and declining population.

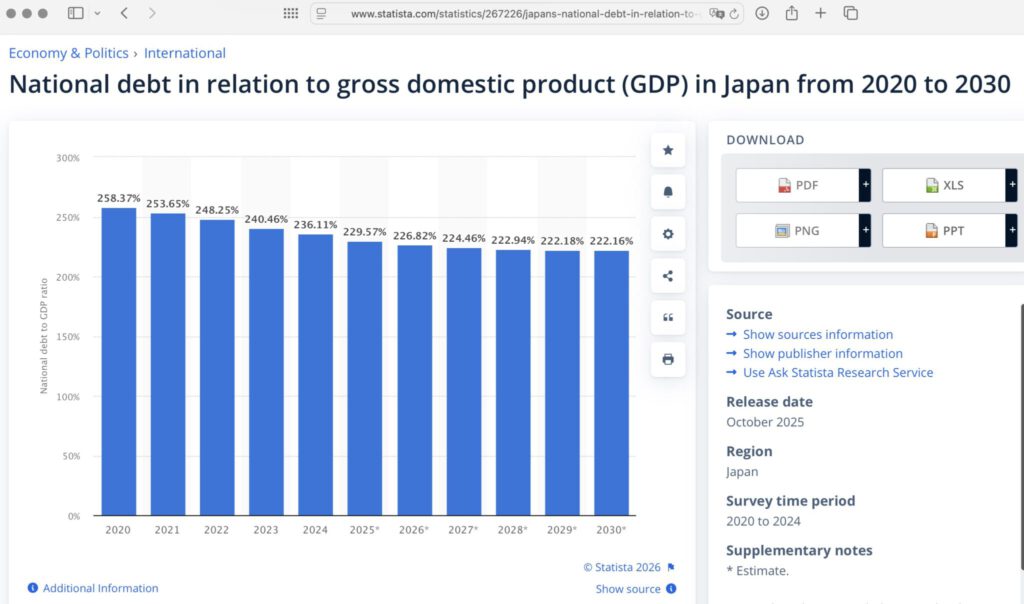

Responsible and proactive public finances

The third pillar is responsible and proactive public finances. We must analyze Japan’s fiscal situation from multiple perspectives and with objectivity, and take it seriously. The concept of “responsible and proactive public finances” represents a forward-looking and proactive approach to fiscal policy — and it is by no means an indiscriminate pursuit of expansion for its own sake. We are determined to achieve both the building of a “strong Japanese economy” and the “sustainability of public finances” in a well-balanced manner, thereby fulfilling our responsibility to the people living today and to future generations. The 2026 budget is designed to align with the medium-term economic and fiscal framework, while taking into account economic and price trends, as we aim to transition the Japanese economy to a new stage. Specifically, the overall budget appropriately reflects economic and price trends. At the same time, we have increased budgets for key initiatives such as strengthening defense capabilities and implementing measures like tuition-free education, while securing the necessary financial resources. Furthermore, we have maintained fiscal discipline, holding down the Bond Dependency Ratio at 24.2 percent — the lowest level in nearly 30 years. In addition, Japan’s fiscal balance as a percentage of GDP has shown an improving trend in recent years. It is estimated that in 2025, the general government fiscal balance-to-GDP ratio of Japan (minus 0.6%) will be the best among the G7 countries. It is essential to transform the fiscal structure to underpin a strong Japanese economy on both the expenditure and revenue sides. By ensuring wise spending and implementing strategic fiscal measures to enhance growth potential, we will curb the rate of growth of Japan’s outstanding debt balance so as not to exceed the rate of economic growth and lower Japan’s ratio of outstanding government debt to GDP. This will bring about the sustainability of public finances and ensure trust from the markets.

Conclusion

Today, the free and open international order we have been used to is wavering, as the world undergoes profound change with rising political and economic uncertainty driven by such as geopolitical tensions. To meet the expectations of young people who believe Japan’s future is bright, we must take bold action. It is our responsibility to make Japan strong and prosperous and pass it on to the next generation. As Japan’s first female Finance Minister, I am committed to building a strong Japanese economy in a time of profound global change, under Japan’s first female Prime Minister, Sanae Takaichi. Together, we will create today we can be proud of tomorrow. Thank you for your attention.

https://www.fsa.go.jp/inter/etc/20260120/01.pdf

2026/1/22 update

[社説]消費税減税ポピュリズムに未来は託せぬ

2026年1月20日 19:15

高市首相は19日の記者会見で食料品の消費税率を2年間ゼロにする考えを「悲願」だと表明した(19日、首相官邸)

高市早苗首相が19日の記者会見で食料品を2年間、消費税の対象から外す考えを表明した。2月8日投開票の衆院選は与野党そろって消費税減税を公約する構図が固まった。日本の財政を「行き過ぎた緊縮」と呼び、恒久的な歳出削減や財源を伴わない無責任な減税ポピュリズムに未来は託せない。

自民党が国政選挙で消費税減税を公約するのは初めてだ。昨年7月の参院選で公約化を見送ったのは政権与党として最低限の矜恃(きょうじ)ではなかったのか。

減税すべきでないのは消費税が国と地方の負担する年金、医療、介護、子ども・子育て支援など社会保障の安定財源だからだ。税収はほぼ個人消費に比例し、企業業績に連動する法人税に比べ景気変動の影響を受けにくい。全世代で社会保障を支える意義もある。

消費税収は所得税や法人税を上回る基幹税の中核だ。もし8%の軽減税率をゼロにすれば地方分も合わせ税収は年5兆円ほど減る。

消費税は大平正芳内閣の一般消費税、中曽根康弘内閣の売上税の相次ぐ挫折を経て、竹下登内閣の1989年に実現した。安倍晋三元首相が2度の延期と引き上げで達成した財源を手放すのが高市首相の「私自身の悲願」なのか。

約50人の経済学者を対象に昨年5月に実施した「エコノミクスパネル」でも消費税減税は「不適切」との回答が85%にのぼる。首相は日本維新の会との連立合意書に基づいて「2年間限定」というが、一度下げた税率を本当に元に戻せるかは疑わしい。立憲民主党と公明党がつくった新党、中道改革連合が公約する「恒久的にゼロ」も安定財源の確保は不透明だ。

消費税には所得が低いほど税負担を重く感じる逆進性があるが、与野党の消費税減税案は富裕層にまで恩恵が及び非効率だ。低所得層に絞った給付付き税額控除の実現を急ぐのが筋ではないのか。

財政悪化への懸念から市場では円安と長期金利上昇が加速している。供給制約下の需要追加、円安による輸入価格上昇の両面から物価高対策としても疑問が多い。「即効性が乏しい」という首相の過去の発言とも矛盾する。

日本経済はインフレで名目国内総生産(GDP)の伸びに比べ金利の引き上げが遅れる「財政のボーナス期」にあるが、選挙のたびに財政規律が緩むようでは困る。与野党は衆院選で財政健全化の目標と道筋も明示すべきだ。

https://www.nikkei.com/article/DGXZQODK199ZE0Z10C26A1000000

2026/2/1 update

令和8年1月31日。高市早苗首相「円安で外為特会ホクホク」 為替メリットを強調

2026/1/31. Prime Minister TAKAICHI Sanae: “The weak Yen makes the Foreign Exchange Fund Special Account happy” – Emphasising the benefits of the exchange rate

https://art-culture.world/politics/prime-minister-takaichi-sanae/

注意!ATTENTION!

All pictures and texts have to be understood in the context of “Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial-NoDerivative Works.” ここに載せた画像やテクストは、すべて「好意によりクリエーティブ・コモン・センス」の文脈で、日本美術史の記録の為に発表致します。 Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial-NoDerivative Works, photos: cccs courtesy creative common sense

All these texts and pictures are for future archival purposes, in the context of Japanese art history writings.

大嫌い--512x256.jpg)